Gareth Thomas: Are celebrity private lives no longer fair game?

- Published

Sports stars Ben Stokes and Gareth Thomas criticised newspapers for intruding on their privacy

For years, aggressive reporting on the private lives of celebrities has driven newspaper sales. Now the media faces legal penalties and public criticism for intruding on famous people's privacy. What changed?

In 1990, the TV sitcom actor Gorden Kaye, a household name for his role in the show 'Allo 'Allo!, was in hospital with serious head injuries after a car crash.

While he was recovering from brain surgery, a journalist from the Sunday Sport entered his hospital room, took photos, and interviewed him in his disoriented state.

Later he sued, but when the case reached the Court of Appeal, it ruled that there was no remedy in English law for a breach of privacy.

"It was a free-for-all for newspapers then," says Mark Lewis, partner at Patron Law who has represented footballers and other celebrities in privacy cases.

'Immoral and heartless'

Now, the tide seems to have turned. This week, newspapers faced a backlash after former rugby player Gareth Thomas revealed that journalists had forced him to go public with his HIV diagnosis.

Then cricketer Ben Stokes condemned a front page story in the Sun about a tragedy in his family 31 years ago as "immoral and heartless".

Lawyers say privacy rights began to change with the passage of the Human Rights Act in 1998, which introduced a right to "respect for private and family life".

The result has been a series of rulings against the media, such as Max Mosley who successfully sued the News of the World for breach of privacy, after it had published pictures of him at an orgy with five sex workers.

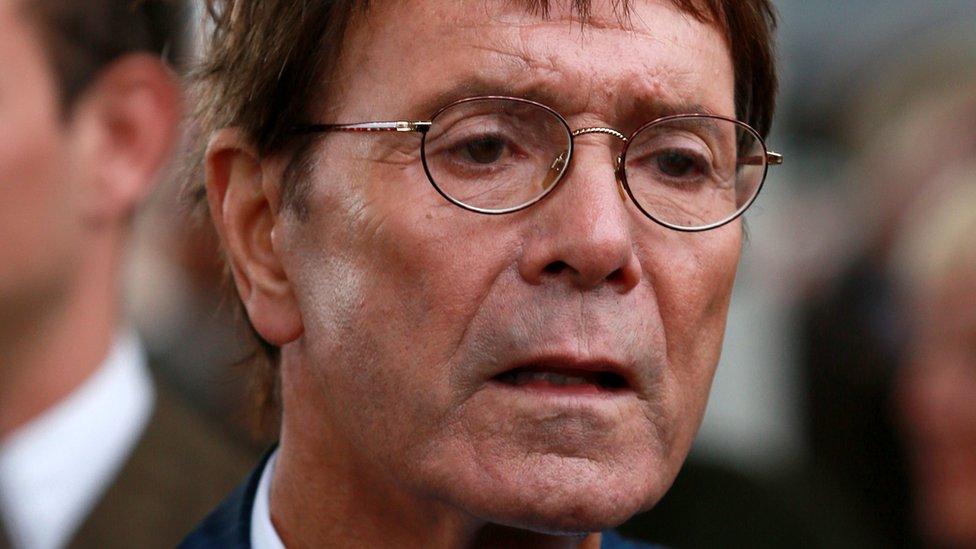

Sir Cliff Richard used the same privacy law last year to win his case against the BBC, which had showed helicopter footage of a police raid on his home. He was never arrested or charged and the BBC paid £2m to settle the case.

The phone-hacking scandal also showed that members of the public could be subject to the same intrusive reporting, with the revelation that missing schoolgirl Milly Dowler's phone had been hacked.

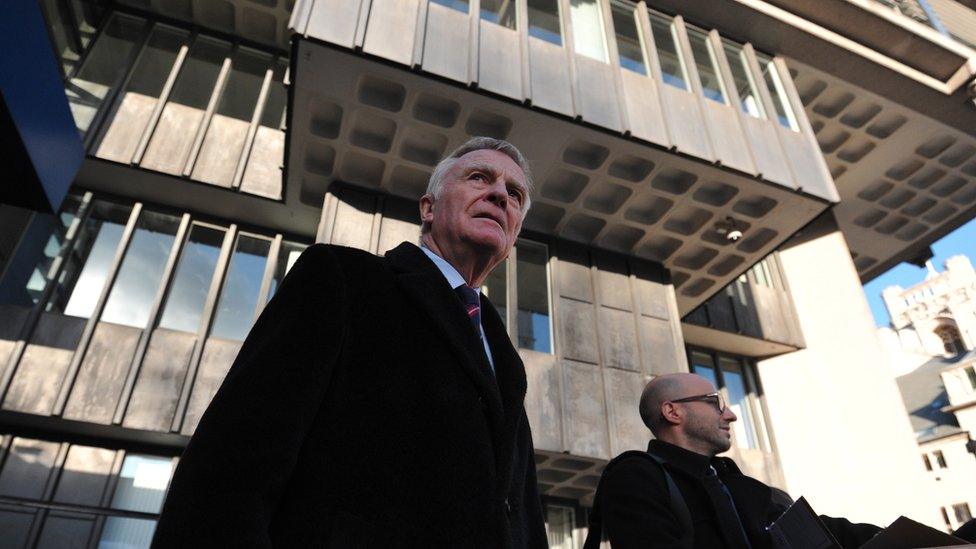

Former Formula One boss Max Mosley became a privacy campaigner after a legal battle with the News of the World

But Mr Lewis says privacy victories in court can be hollow for celebrities, because the damage caused by the intrusion cannot be repaired once the story is already out. "Privacy is like virginity: once it's gone, it's gone," he says.

Where does the dividing line between free speech and privacy lie? Mr Lewis says every case is unique.

He says he has acted for a woman who says her former husband, a Dubai-based businessman, was trying to deny he was married to her or had fathered her child by using privacy laws to silence her. "There are stories that shouldn't be blocked and need to get out," he says.

But he suggests not protecting privacy can also have serious consequences. After the extra-marital affairs of former footballer Garry Flitcroft were revealed in the press, Mr Flitcroft said his father stopped watching his matches because he was upset by the fans' chants. Later his father, who suffered from depression, killed himself.

Boycott calls

Paul Connew, a former deputy editor of the News of the World and editor of the Sunday Mirror, told BBC Radio 4's PM programme that editors rely on their individual judgement and taste.

But he says increasingly the public are having their say on social media. "The Sun have taken a risk here. Look at social media, there's a backlash, there are calls to boycott the Sun," he said.

"It may turn out to be a one-day circulation booster that actually loses more circulation in the days and weeks to come."

The court of public opinion may be the only one celebrities such as Ben Stokes can appeal to after their privacy has been invaded.

Mr Connew said press regulator Ipso is unlikely to take action against papers for digging up something that was already in the public domain many years ago.

Barbra Streisand proved celebrity attempts to protect privacy can backfire

But social media has also been used to undermine privacy laws. Footballer Ryan Giggs was named on Twitter after he took out an injunction intended to prevent an alleged affair becoming public knowledge.

The phenomenon even has a name - the Streisand Effect - where an attempt to hide information only makes it spread more widely.

It is named after the entertainer Barbra Streisand, who tried to suppress photographs of her Malibu home, only to draw even more public attention to them.

'Outrageous breach'

Angela Philips, a professor of journalism at Goldsmiths University in London, who gave evidence to the 2012 Leveson Inquiry into press regulation, said she believed the Ben Stokes story was an "absolutely outrageous breach of simple human ethics" on the part of editors.

"This story did not directly affect Ben Stokes himself, it was about his parents, who had no possible way of being able to control the story," she told BBC News.

"It wouldn't have come out had Ben Stokes not been at the height of his fame."

She added: "This decision to turn upside down the lives of two people was made on pure commercial grounds. I think that the wave of anger on social media could very well turn out to be damaging to them in future."

'You've made yourself a target'

Mr Lewis said celebrities now expect such a backlash, often led by the media.

"The law is very good now to stop privacy intrusions, but the practice is not good. If you go out and get an injunction, you can stop a story. But more than that, you've made yourself a target," he said.

"Ask Sir Philip Green, does he enjoy having got the injunction?" The retail tycoon gagged the Daily Telegraph from publishing allegations of misconduct, including sexual and racial abuse.

Eventually he was named in Parliament, leaving him with a reported £3m legal bill and the "bulk" of the Telegraph's legal costs.

Mr Lewis said: "He might not be as enthusiastic as he once was."

- Attribution

- Published17 September 2019

- Published18 September 2019

- Published12 April 2018