The places knife crime is rising fastest

- Published

Lydia Lawrence has been stabbed twice but now helps others to avoid the dangers of knife crime

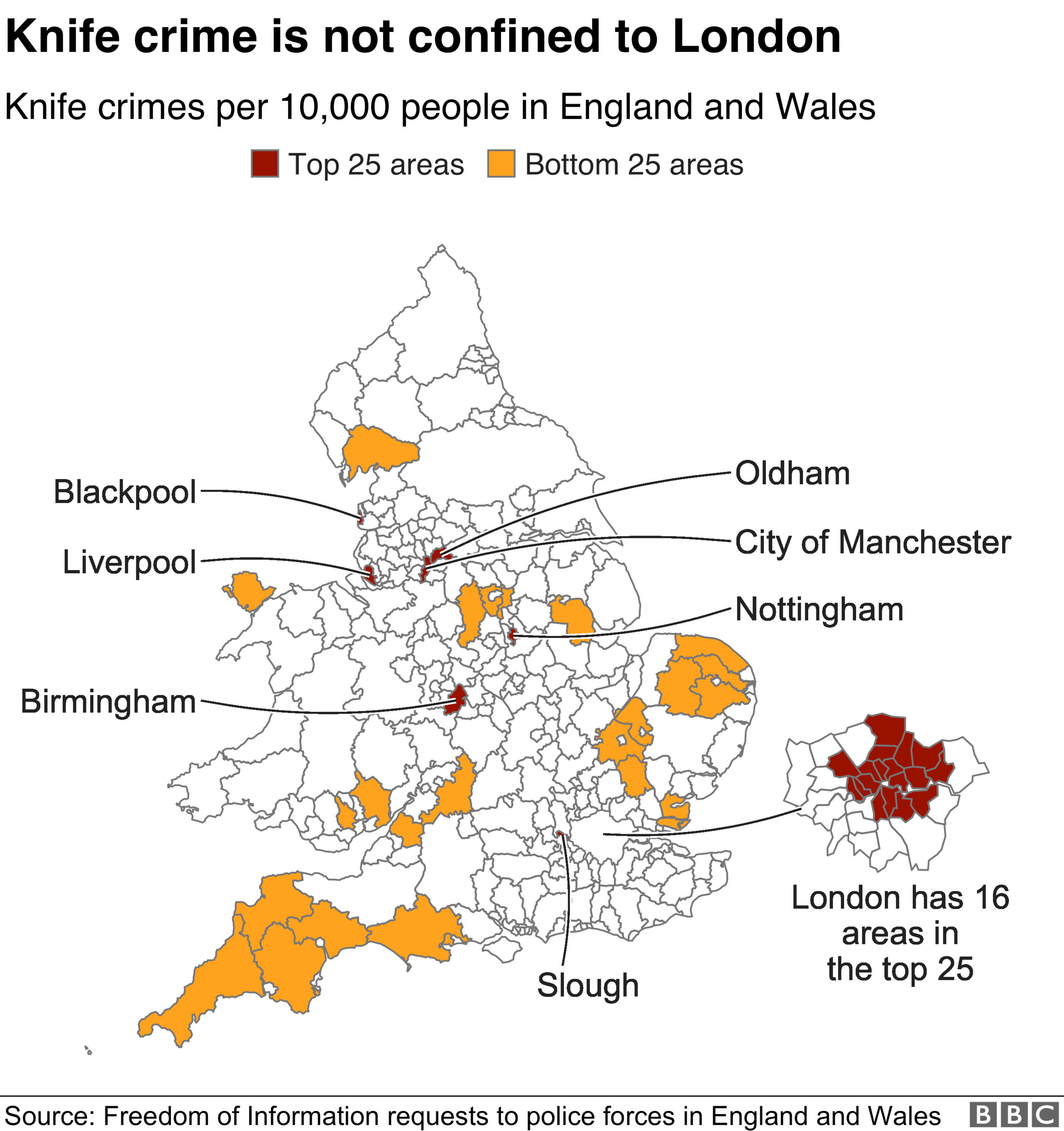

The rate of knife attacks in some regional towns and cities is higher than in many London boroughs, BBC analysis of police figures suggests.

Overall, London remains the most dangerous part of England and Wales - but data, obtained from 34 of the 43 police forces, shows the rate of serious knife crime offences rising sharply in some areas outside London, and outstripping some of the city's boroughs in places like the city of Manchester, Slough, Liverpool and Blackpool.

"We are suffering just as much as anywhere else," said Byron Highton whose brother Jon-Jo was 18 when he was stabbed to death with a sword and an axe as he walked home in Preston, in 2014.

"The whole country is suffering from knife crime, but small cities in the north like Preston get no mention."

Under Freedom of Information Law, the BBC asked all 43 regional police forces in England and Wales for details of serious knife crime in their area.

Serious knife crime is defined as any assault, robbery, threat to kill, murder, attempted murder or sexual offence involving a knife or sharp instrument.

In Lancashire, the figures show knife crime has doubled in five years, rising from 455 offences in 2014, to 981 in 2018.

Sorry, your browser cannot display this map

Jon-Jo had survived a previous attack the year before when he was stabbed 24 times with a machete.

Byron, who has suffered from depression since witnessing one of the attacks, now works for Safety Guide Foundation, external, giving knife crime talks in schools across north-west England.

"Young people have a lack of respect for life," he said.

"The scary part is how bad is it going to be in 10 years if this generation isn't fixed."

Byron Highton witnessed one of the attacks on his brother

Manchester, Liverpool, Slough and Nottingham are all in the top 25 most dangerous places in England and Wales for serious knife crime.

The safest areas with less than one crime per 10,000 people include Dorset, the Cotswolds, Monmouthshire and the Malvern.

In Scotland, police collect crime statistics differently, so there are no separate records for knife attacks. However, knife possession has increased in recent years, with more than 2,300 crimes reported last year.

The girl 'threatened with a machete'

It's not just young men who are affected. In Blackpool, students Keeley, 17, and Lauren, 18, have both been threatened on the estate where they live, with knives brandished in relatively trivial teenage disagreements.

"I got threatened with a machete in a park by a group of lads when I was playing football," Keeley said.

"They wanted to play in our half, but we said no."

Students Lauren (l) and Keeley have both been threatened with stabbing near their homes

Lauren says she doesn't feel safe in the town: "Me and my mate were walking home and a guy came out and threatened to stab one of my mates."

In 2018, the resort had 14.3 serious knife crime offences per 10,000 people, putting it in the top 25 most dangerous places for knife crime in England and Wales, of the 275 areas which gave data.

Drugs gangs, school exclusion rates, poverty, unemployment and cuts to services have all been blamed for a rise in youth violence in towns like Blackpool and Preston.

Last month, official figures showed eight of the 10 most deprived neighbourhoods in England were in Blackpool.

"There is a significant issue with county lines [drugs courier] gangs in Blackpool, and from that we are seeing that means a lot of young people are carrying knives," Ashley Hackett, chief executive of Blackpool Football Club Community Trust , external, told the BBC.

"We have an awful lot of children and teenagers who are living in deprivation and whatever way they can find to earn money and support households, legally and illegally, they are doing it. That includes drugs and knives," he added.

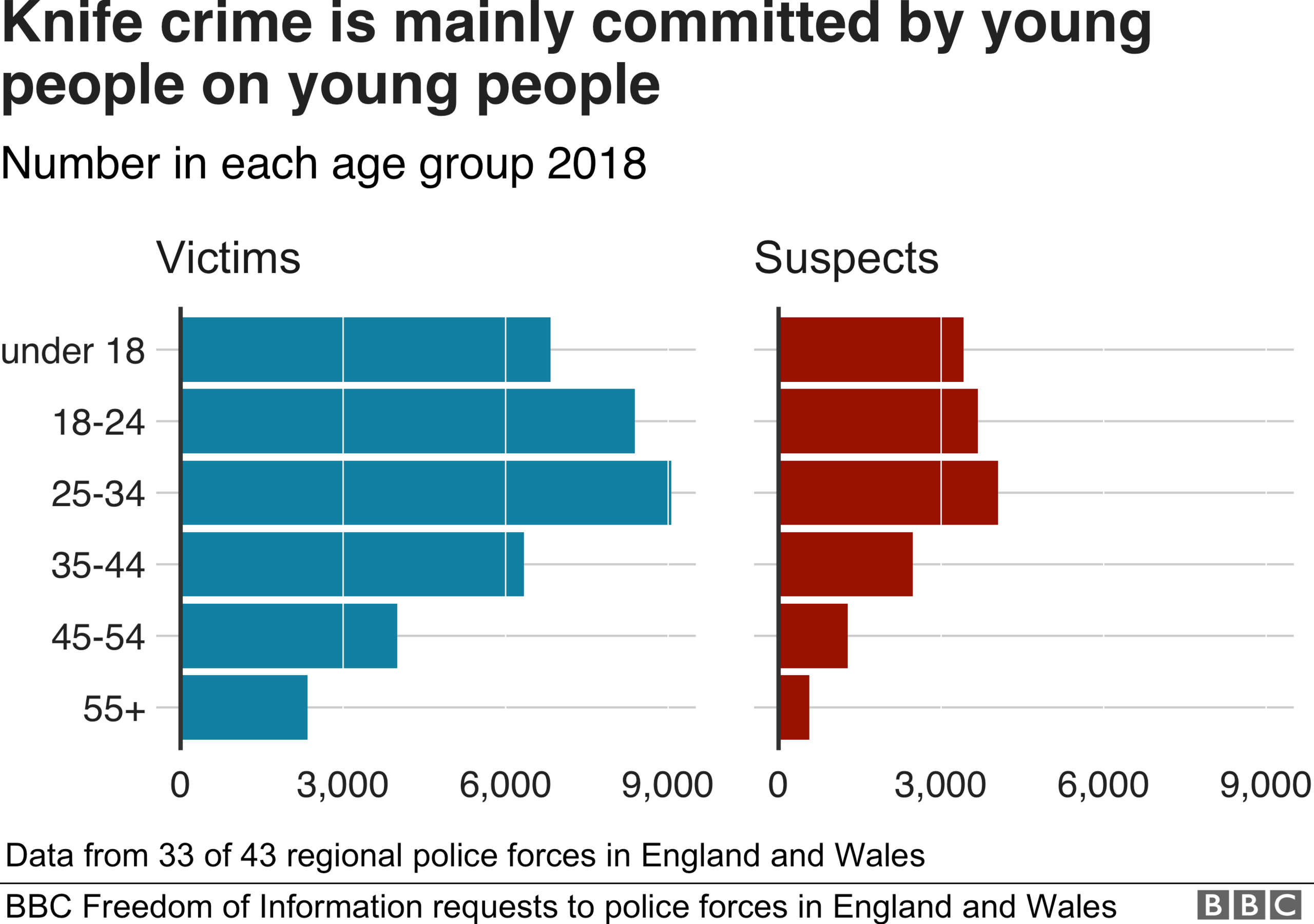

In 2018, almost half of all suspects in serious knife crime offences in England and Wales, were aged 24 and under.

'Emotionally exploited'

The experiences of young women like Keeley and Lauren are becoming more commonplace.

Last year, 15% of knife crime suspects were female and, including those attacked in domestic abuse incidents, a quarter of victims of knife crime were women.

Dr Mike Rowe of Liverpool University, who has been observing police officers at work for the past six years, told the BBC: "Girls and young women are being exploited to carry weapons because they are much less likely to be stopped and searched by police.

"The attention on male suspects may lead to the deliberate recruitment of young women."

Anti-knife crime campaigner Lydia Lawrence, who has herself survived two stabbings by two different women, agrees that gang violence is on the rise, and girls with low self-esteem are being emotionally exploited.

Ms Lawrence, who's from west London, was first a victim of knife crime aged just 12, when she was cut on her face.

She nearly died when she was 21, after being stabbed through her kidney and liver.

Ms Lawrence, who was born in prison, excluded from school at 12 and homeless by 16, warned that girls from troubled backgrounds and broken homes are the most at risk.

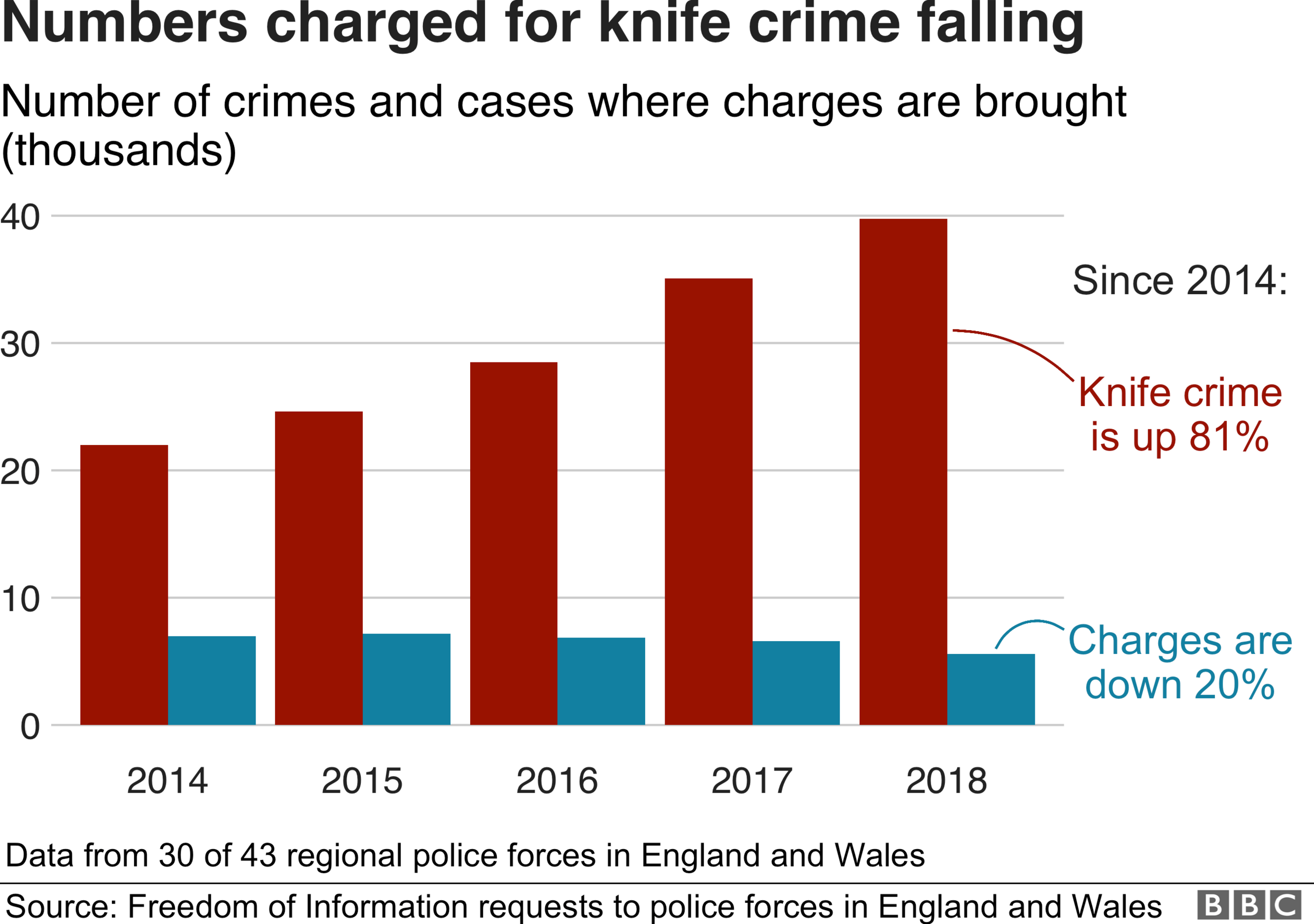

Dr Rowe believes police responses to knife crime have been "seriously hampered by the cuts in the past eight years and more", contributing to a fall in the number of cases solved.

He said that every time there is a stabbing, officers are pulled from neighbourhood teams to guard the scene as forensics are gathered.

"It's these neighbourhood teams that would normally be expected to gather the intelligence which investigations of knife crime and gang activity rely on.

"So there is a vicious cycle in which rising demands hinder the capacity to investigate those very crimes."

Assistant Chief Constable Jackie Sebire, the national lead in tackling serious violent crime at the National Police Chiefs' Council, blamed police funding cuts for the fall in charge rates.

"The large reduction in police funding since 2010 has meant fewer detectives with less time and a bigger workload taking on long investigations, meaning it can be more difficult to get a charge.

"In some cases police have fearful witnesses, and victims who do not feel able to engage with officers or the court process.

"This means there is little possibility of a prosecution.

"Some forces who have been given additional funding to tackle violence are using that to improve forensic capabilities, so even when the victim is unwilling to proceed, police can still progress a case."

A Home Office spokesperson responded: "We are taking action to tackle the violent crime which has such a devastating impact on our communities.

"This includes supporting the police by recruiting 20,000 new police officers over the next three years, making it easier for them to use stop and search powers, and investing £10m in additional funding to allow forces to increase the number of officers carrying Tasers."

- Published18 July 2019

- Published17 May 2019