Gang murder investigations blocked by 'wall of silence'

- Published

CCTV shows some teenagers still holding table tennis bats as others ran for their lives

Police investigations of gang murders are increasingly held back by a "wall of silence", the BBC has found, with witnesses across the country unwilling to give evidence. The trend emerged during the BBC's First 100 Killings project which has tracked homicides from the start of 2019 and monitored dozens of murder trials. Youth workers, police and prosecutors believe witnesses are afraid for their own safety.

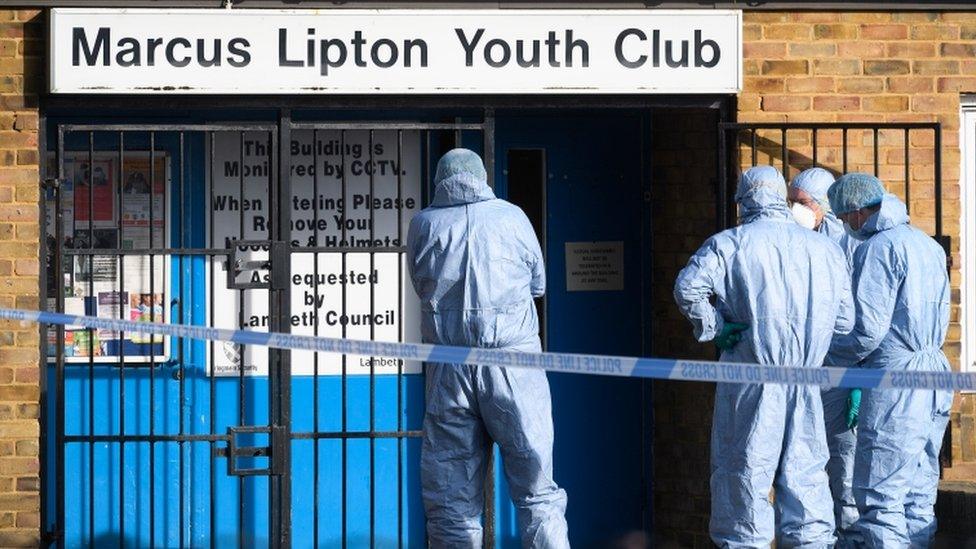

On a February evening in 2019, the Marcus Lipton youth club in Brixton, usually a place for children to socialise in safety, was about to erupt in violence.

Outside, a BMW pulled up and two teenagers, armed with long knives, ran towards a group gathered near the entrance and chased them inside.

David Marriott, 38, was in the sports hall running a football coaching session for Lambeth Tigers with children as young as three.

"Everything happened really fast…The boys came running through the hall that we were working in. Everyone was really alarmed," he remembers.

One of the young men who was being chased - 23-year-old Glendon Spence - fell over and was cornered by the two attackers near a table tennis table.

He received stab wounds to his hand and arm as he fought to fend off the blows.

Then a blade slashed his thigh, penetrating a major artery.

His assailants ran out and back to the car, which was later burnt out and abandoned.

Meanwhile Mr Spence managed to struggle to his feet, before collapsing in a heap.

"He was bleeding really heavily," says Mr Marriott. "We found where he had been stabbed and where the blood was coming from and we tried to stop the blood coming out."

It is still not clear whether Glendon Spence, 23. was the intended target

But despite his best efforts and those of paramedics, the young man died on the floor of the youth club he had attended since his childhood.

"It was very difficult. The young children saw blood everywhere," says Mr Marriott. "Some of them are still trying to get over it."

Mr Spencer's killing was one of 100 in the first four months of 2019 which were tracked by the BBC as we looked into the reasons for the recent spike in homicides.

The youth centre became a crime scene and a murder investigation was launched - but police hit an early obstacle as key witnesses would not talk to them.

This made it difficult to understand the motive and whether Mr Spence or any of the people he was with, were the intended target of what police suspected was a gang attack.

"It's unclear in this case who the intended gang were, or even who the attacking gangs are," says DCI Richard Vandenbergh, who leads a homicide team based at Lewisham Police Station.

The attackers were armed with long knives

Officers focused on what they could prove and had an early breakthrough.

In the melee a youth worker overheard a reference to "R1".

A gang intelligence officer worked out this was the street name for Rishon Florant, then aged 17, who had links to a south London gang and a string of convictions for knife possession.

He had also been excluded from school and banned from entering Lambeth at the time of the murder.

Florant's name was immediately circulated to police and border officials at ports across the country.

"He was actually found trying to leave the country at Heathrow Airport and was boarding a flight en route to Uganda," says DCI Vandenbergh.

Fingerprints and CCTV

Now the hunt was on for the second suspect.

Sifting through CCTV at the youth club, officers saw he had touched an outside gate and the table tennis table close to where Mr Spence was stabbed.

Unlike Florant, this suspect was not wearing gloves so police were able to extract a fingerprint.

In the national DNA database they found a match to Chibuzo Ukonu, another 17-year-old youth with a criminal record for knife possession and drug dealing.

He was tracked to Manchester where he was arrested.

Rishon Florant (r) was convicted of murder and Chibuzo Ukonu (l) of manslaughter

The pair were charged and put on trial at the Old Bailey.

Florant was convicted of murder and jailed for a minimum of 18 years.

As he walked from the dock to the cell, he smiled at his friends in the public galley when they shouted 'Free R1". He has lodged an appeal against his conviction.

Ukonu was found guilty of manslaughter and will serve 14 years in a young offender institution.

Although Mr Spence's parents can take some comfort from these verdicts, they are still no clearer as to why their son was killed.

Not knowing the motive leaves a huge gap in understanding what this homicide was all about, "frustrating" for DCI Vandenbergh who wants to understand the background to help prevent others. The men's accomplices, such as the driver of the BMW, have still not been caught.

But it's not the first time DCI Vandenbergh has come up against the wall of silence.

"It's incredibly common, especially with some of the under-25 knife crime murders that we have where there may be gang links. We've had instances where people will just not talk to us," he says.

Mr Marriott understands why: "No-one wants to be labelled as a grass or a snitch, and if people do go down that road there will be consequences."

They "could be beaten up, someone could get killed" and "as much as the police will have an opinion that these boys should come forward, it's easier said than done. Because if they were to come forward, what would the police do to protect them?".

Football coach David Marriott says he can understand why witnesses are unwilling to come forward

His assessment is bleak: "I wouldn't advise that they come forward. They've got to turn a blind eye to it."

For Mr Marriott, who grew up in Brixton, the key is to prevent the violence happening in the first place. That means offering more support for community groups like his, which help 500 local boys.

"We do everything we can to get the kids off the street but lack of facilities is a huge problem," he says.

Friends of Kamali Gabbidon-Lynck left candles where the 19-year-old was stabbed to death in north London

In the 100 killings cases followed by the BBC we have seen how often gang disputes and turf wars escalate into deadly violence.

In October, two men and three teenage boys went on trial accused of murdering a rival gang member in a north London hair salon.

Kamali Gabbidon-Lynck, 19, bled to death in front of people, including children.

Earlier his friend Jason Fraser, 20, had been shot and stabbed eight times in Wood Green in scenes that "were reminiscent of a Hollywood film", an Old Bailey trial heard.

Murder convictions were secured but once again we glimpsed the price that can be paid for not keeping quiet.

One of the teenage defendants was stabbed in prison because he had given an account to police, albeit very limited, of what happened that night.

'Stand up and be counted'

"In most of the gang violence that we prosecute, there are witnesses who have plainly seen something which would be relevant to the prosecution but are not prepared to give evidence," says Julius Capon, head of the Homicide Unit of the Crown Prosecution Service in London.

He believes it's getting worse.

Julius Capon, head of London's CPS Homicide Unit, says witnesses are increasingly fearful

"We're getting more instances of knife and gang crime and as a result we're getting more people who are reluctant to come forward," he says.

For prosecutors like Mr Capon their reticence is "an enormous handicap", meaning that "injustice is being caused, because those that have killed people are not facing the justice they should".

He acknowledges that people are afraid: "Frankly anyone that has witnessed a murder will be frightened about the repercussions but there are measures that we can put in place to protect people."

And besides, people have "a moral obligation to do your bit and come to court to give evidence".

"If you are worried about the number of, usually kids, that are being killed you have to stand up and be counted."

Back on the streets of south London, homicide detectives are struggling to breach another wall of silence.

It is more than a year since the unsolved murder in Tulse Hill of 16-year-old John Ogunjobi, who was chased and fatally stabbed by a group of men.

He died in front of his mother in a targeted attack.

DCI Vandenbergh believes that some of John's friends may have vital information that they have not given police and appeals to their consciences to help a grieving mum to know why it was that her son was targeted.

Jackie Sebire, national lead on serious violent crime at the National Police Chiefs Council, said there is a "group of disengaged young people" who do not trust "any authority figures", including police, teachers, and youth workers.

She told Radio 4's Today programme it would "absolutely" help if more witnesses and victims could remain anonymous.

But she said that decision was up to the judge presiding over the case, and that applications for anonymity may be rejected to protect the defendant's right to a fair trial.

- Published17 May 2019

- Published11 October 2019