Streatham attack: Will terror sentence changes stop offences?

- Published

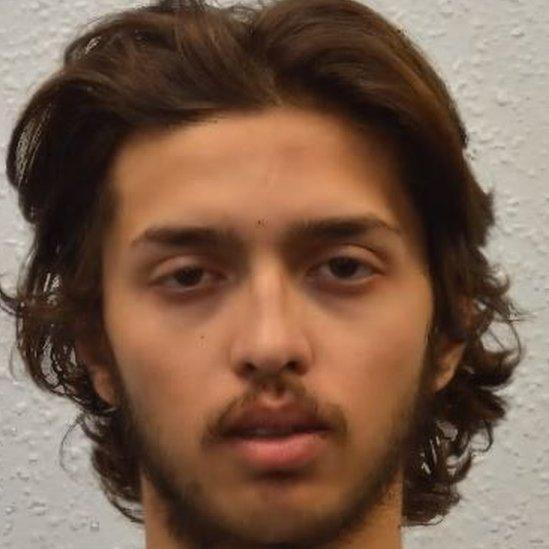

Teams have been searching the area after Sunday's attack in Streatham

The government wants to end the automatic early release from prison of terror offenders, following two attacks by men convicted of terror offences in recent months. But what legal challenges could ministers face and how effective might the changes be?

There are critical questions for the government that arise in relation to the proposals to end the automatic early release of offenders convicted of terrorism offences.

The first is what legal challenges the government might face.

The bigger question is whether the proposed changes will have the effect of stopping the kind of attack we saw in Streatham at the weekend.

Legal challenges

Every judge who sentences a convicted defendant is under a statutory duty to explain the sentence that is being passed.

So, offenders like Sudesh Amman are told by the judge in open court that they are being sentenced for a fixed period, known as a "determinate" sentence.

They are told that they will be automatically released at the half-way point and serve the remainder of their sentence on licence in the community. That means that they have a "legitimate expectation" of being released at the half-way point.

Indeed, some offenders will have pleaded guilty on the basis that they will be given a "determinate" sentence with automatic early release at the half-way point.

Sudesh Amman stabbed two people in south London on Sunday before being shot dead by police

Changing the release date retrospectively to the two-thirds point would inevitably lead to legal challenge that the offender's "legitimate expectation" of automatic "half-way" release had been unlawfully tampered with.

That argument for terrorism offenders would have little if any public support.

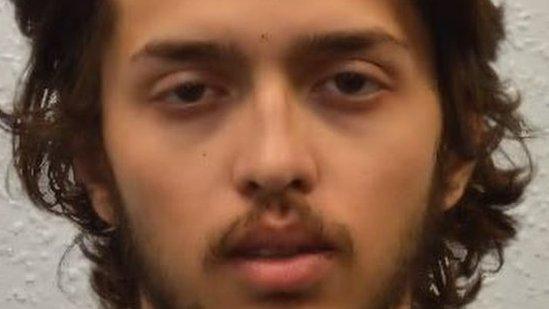

Legal correspondent Clive Coleman looks at why Usman Khan, who carried an attack on London Bridge in November 2019, was freed from prison

The government would argue that they are simply changing the way in which the fixed-term sentence is administered and that is entirely lawful. There is support for that position in existing case law.

Other legal challenges could be brought on human rights grounds. Under Article 7 of the Human Rights Act, "No Punishment Without Law", it can be argued that an offender cannot be given a heavier punishment than was available to the court at the time they were sentenced.

It could also be argued that to do so interferes with the right to a fair trial - Article 6.

Would the changes work?

In cases like Sudesh Amman, moving the early release date from the half-way point to the two-thirds point would make a difference of six months.

Many argue that is merely a stop-gap measure and would only protect the public for a short additional period.

If, as the government proposes, release at the two-thirds point is not automatic but subject to an assessment by the Parole Board, that would certainly provide an additional layer of protection for the public.

The board would make an independent assessment as to whether the offender posed a risk and could prevent release - meaning that entire sentence is served.

However, that additional period - the remaining third - may itself only be a matter of months. It would also have the consequence of reducing or extinguishing any period served on licence.

That would reduce the chance to supervise the offender once they are released.

Are there any alternatives?

Many senior legal figures believe that the only truly effective way of dealing with the problem is to re-introduce Indeterminate Sentences for Public Protection or IPPs, which came into force in 2005.

Under these a judge passed a tariff, or minimum sentence which the offender had to serve in prison. It reflected the seriousness of the crime.

Once it was served, the offender had to apply to the parole board for release.

The board would not release the prisoner if it considered that they still posed a risk. However, IPPs, which became known as the "new or de-facto" life sentences, were incredibly controversial.

They were meant for a hardcore of dangerous offenders but thousands were passed, some with minimum terms of months not years, and thousands languished in prison unable to satisfy the Parole Board that they were no longer a risk to the public.

This was sometimes because, for instance, it was almost impossible for an offender with a borderline personality disorder, to satisfy the Parole Board that they had changed.

Tackling the risk posed by those convicted of terrorism offences, especially those at the lower end serving short sentences, is complex.

There is a desperate need for action to prevent attacks, but no easy answers.

- Published4 February 2020

- Published3 February 2020

- Published3 February 2020

- Published2 February 2020