Emergency law aims to stop next terror release

- Published

Mohammed Zahir Khan is due to be freed at the end of this month

Ministers are aiming to pass emergency legislation to block the automatic early release of convicted terror offenders before the next one is due to be freed in three weeks' time.

Sunderland shopkeeper Mohammed Zahir Khan, 42, is expected to be released on 28 February after serving half of his sentence for encouraging terrorism.

An official said legislation would be introduced to the Commons on Tuesday.

It follows attacks in recent months by men convicted of terror offences.

Khan was arrested in 2017 and given a four-and-a-half year sentence in May 2018 after pleading guilty.

He had posted a statement on a Twitter account from the Islamic State group calling for attacks. He also admitted a charge of distributing material designed to incite religious hatred after calling for Shia Muslims to be burnt alive.

The government's emergency measures, which require backing from Parliament, would postpone his release until the Parole Board has given its approval.

Ministers have admitted they are likely to face a legal challenge over the plans and an ex-independent reviewer of terror legislation, Lord Carlile, said blocking early release "may be in breach of the law".

But Justice Secretary Robert Buckland maintained the government was taking the right action, adding: "This is about public protection - it's the first job of government to get that right."

In December, following the London Bridge attack, Prime Minister Boris Johnson had told the BBC's Andrew Marr show that "you can't go back retrospectively" when it comes to sentencing.

How does early release work?

Offenders are told they are being sentenced for a fixed period and will be automatically released at the half-way point, to serve the remainder of their sentence on licence in the community.

Some offenders will have pleaded guilty on the basis that they will be given a sentence with automatic early release at the half-way point.

Their release is an automatic process and does not involve oversight of the Parole Board.

The measures are being introduced after three recent incidents involving men who had been convicted of terror offences.

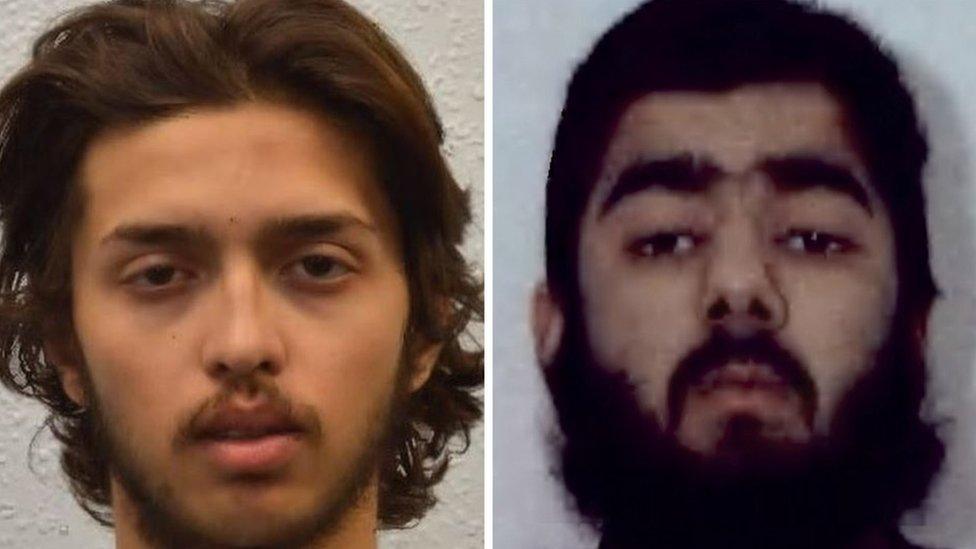

On Sunday, Sudesh Amman, 20, stabbed two people on Streatham High Road, south London, before he was shot dead by police. He had been released from jail 10 days earlier, having served half of his sentence, and was under police surveillance

The attack at Fishmongers' Hall on London Bridge last December by Usman Khan, who had been released half-way through a 16-year sentence for terror offences

An attack on prison officers at Whitemoor Prison last month in which at least one prisoner found guilty of a terrorist offence is understood to have been involved

On Wednesday, the head of UK counter-terror policing Neil Basu warned the threat from terrorism was not diminishing and that the number of subjects of interest and convicted terrorists due for release meant "we cannot watch all of them, all [of] the time".

The first requirement for any government wishing to pass emergency legislation is to show there is an emergency - a set of events which has come about suddenly, could not be foreseen and carries a wider threat.

Is that the case here?

Ministers have certainly been rocked, and the public alarmed, by three similar terror attacks in two months - at Streatham, Fishmongers' Hall and Whitemoor Prison - and are aware of the the risk of further "copycat" incidents.

But the dangers posed by terrorist prisoners have been known for years while the authorities will have been aware of the release dates of particular inmates from the moment they were sentenced.

To obtain Parliament's approval for emergency action, and win any legal challenge on the need for applying the measures retrospectively, the government will have to make a convincing argument that there has been a fundamental change in national security that couldn't have been dealt with before.

- Published5 February 2020

- Published4 February 2020

- Published4 February 2020

- Published6 February 2020

- Published3 February 2020