Seven female scientists you may not have heard of - but should know about

- Published

Not a single woman's name features in the national curriculum for science, an education charity says - prompting calls for the government to act over a "lack of visible role models for girls".

Teach First has launched the STEMinism camapign, calling to close gender gaps in science and maths careers.

It says no female scientists were mentioned in the GCSE science curriculum, while just two - DNA pioneer Rosalind Franklin and paleoanthropologist Mary Leakey - were referred to in three double science GCSE specifications from the major exam boards. In comparison, more than 40 male scientists or their discoveries were mentioned.

Meanwhile, a separate poll conducted by the charity revealed half of people are unable to name a single female scientist, alive or dead.

But it is not just Britain's men who have made pioneering scientific discoveries. Here are some of the overlooked British women whose research changed the world.

Mary Somerville (1780 - 1872)

Astronomer

Born in: Jedburgh, Scotland

Somerville was named the 19th Century's "queen of science" after her death.

Her popular books linked up and explained different areas of scientific study, and her detailed work on the solar system was influential in the discovery of Neptune.

She made history in 1835 when she jointly became the first female member of the Royal Astronomical Society in London.

Somerville has been on the Royal Bank of Scotland's £10 notes since 2017.

Mary Anning (1799 - 1847)

Palaeontologist

Born: Dorset, England

A self-taught pioneer, Anning discovered Jurassic remains in her hometown of Lyme Regis.

She came across her first find - an ancient reptile later named an Ichthyosaurus - at the age of 12.

The Natural History Museum calls her the "unsung hero of fossil discovery", as the scientific community was reluctant to recognise her contributions to science during her lifetime.

She was not allowed to be part of the Geological Society of London, for example. In fact, it did not admit women until more than half a century after her death.

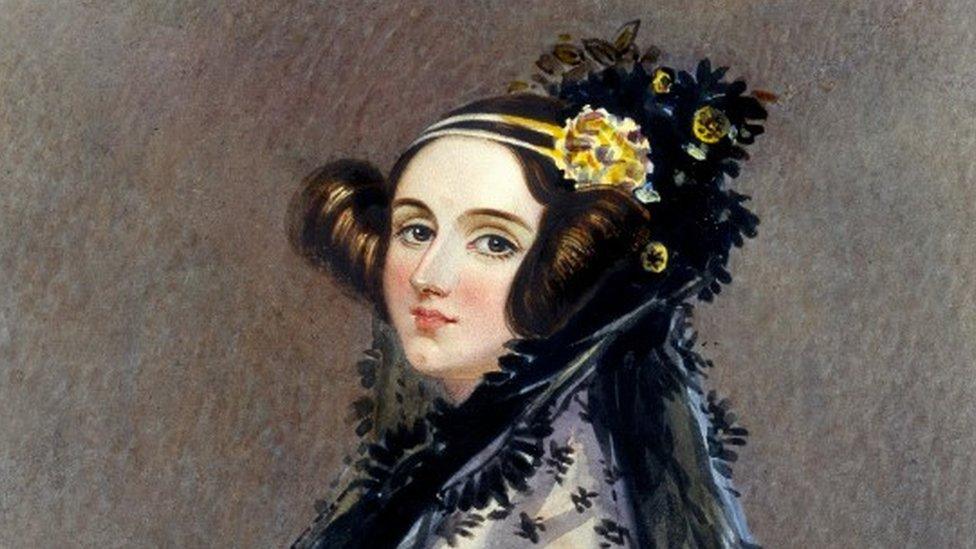

Ada Lovelace (1815 - 1852)

Mathematician

Born: London, England

Ada Lovelace was a leading 19th century mathematician credited with creating early computer programs.

She worked with her friend Charles Babbage, an inventor and mechanical engineer, on his proposals for an "Analytical Engine".

The device was never built, but the design had the essential elements of a modern computer.

Her notes described how codes could be created for the handling of letters, symbols and numbers.

She also created a method for the machine to repeat a series of instructions - a process known as "looping", which computer programs still use today.

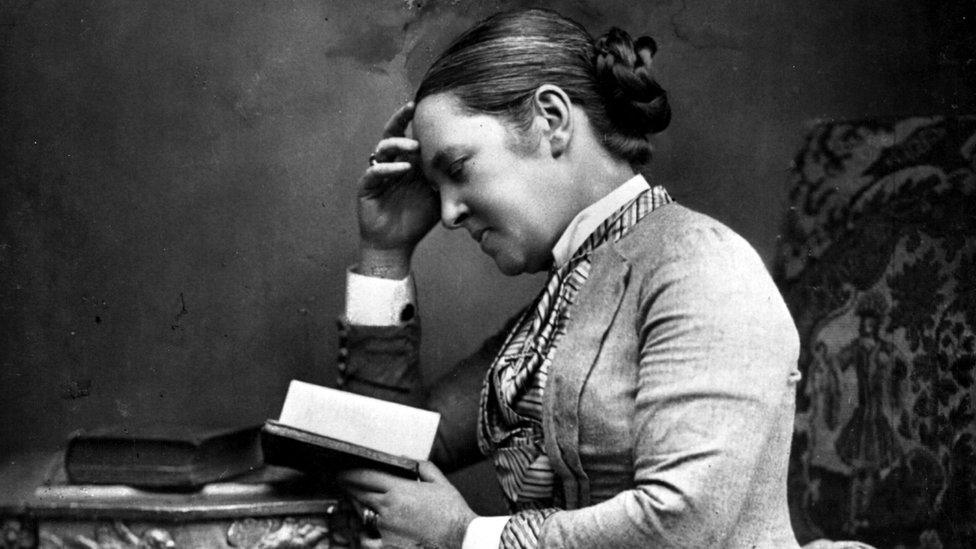

Elizabeth Garrett Anderson (1836 - 1917)

Doctor

Born: London, England

Garrett Anderson was the first woman to qualify in the UK as a doctor - but it wasn't easy to get there.

In her mid-20s, she enrolled as a nurse at the Middlesex Hospital in London.

She attended lectures and observed the male medical students, but no university would let her take the exams to become a doctor.

However, after finding that the Society of Apothecaries couldn't legally refuse her, she qualified in 1865.

She subsequently opened the St Mary's Dispensary for Women and Children in London and co-founded the London School of Medicine for Women.

She was the sister of Suffragist leader Millicent Garrett Fawcett, and campaigned for women's right to vote.

Elsie Widdowson (1906 - 2000)

Dietician

Born: Surrey, England

Widdowson devoted her life to improving people's diets in Britain and overseas.

In 1940, when food was being rationed during World War Two, she published a book called The Chemical Composition of Foods that contained details of the nutritional values of many foods.

She was one of the dieticians who oversaw the addition of vitamins to food during wartime rationing.

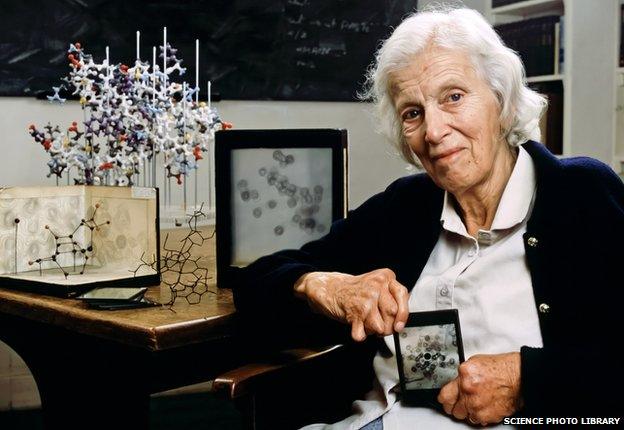

Dorothy Hodgkin (1910 - 1994)

Chemist

Born: Cairo, Egypt

Hodgkin was born in Cairo to a British couple who were working in the north African country during a period when it was under British control.

But she herself largely spent her childhood in Norfolk and was educated at a state school in Beccles, Suffolk, where she fought to be allowed to study chemistry along with the boys.

She used X-ray technology to discover the structures of penicillin, insulin, and vitamin B12.

In 1964 she won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry - and is still the only British woman to have done so.

She also lectured former Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, who studied chemistry at Somerville College in Oxford in the 1940s.

From 1976 to 1988, Hodgkin was president of the Pugwash Conference, an international organisation set up in the 1950s to assess the dangers of nuclear weapons.

Jocelyn Bell Burnell (1943 -)

Astrophysicist

Born: Lurgan, Northern Ireland

Professor Dame Jocelyn Bell Burnell is credited with one of the most important discoveries of the last century: the discovery of radio pulsars.

Pulsars are the by-products of supernova explosions that make all life possible.

Prof Bell Burnell was overlooked for the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1974, even though the award went to two male academics who worked alongside her.

- Published2 February 2020

- Published13 October 2020

- Published18 March 2019

- Published6 September 2018