Thatcher and Hodgkin: How chemistry overcame politics

- Published

To commemorate the 50th anniversary of Dorothy Hodgkin's Nobel Prize, a play - The Chemistry Between Them - has been written, looking at her friendship with Margaret Thatcher. Its creator Adam Ganz describes their ongoing mutual respect.

In 1964 Margaret Thatcher's personal fortunes were at a low.

The Conservative Party had just lost an election. Husband Denis had turned 50 and was approaching complete exhaustion.

He'd gone to South Africa for a rest and it wasn't clear if he was going to come back. Some have speculated the couple might have been close to divorce.

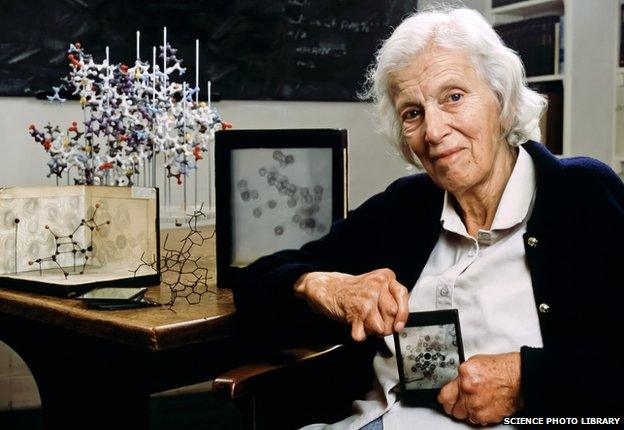

At the end of October Dorothy Hodgkin, Margaret's former lecturer at Somerville College in Oxford, won the Nobel Prize for Chemistry.

Dorothy Hodgkin continued to press the case for nuclear disarmament

Fifty years later she's still the only British woman to have been awarded a Nobel Prize for science.

When Margaret heard the news on the BBC, it was, I think, a major turning point in her political career.

If the woman who'd sat across the room from her in tutorials for four years could achieve the highest honour in her chosen field, what was to stop Margaret reaching the pinnacle in hers?

She read beyond the headlines saying "Nobel Prize for British Wife" and saw a familiar figure achieving greatness. Dorothy was 54 years old - exactly the same age Margaret was when she became prime minister.

They were two of the most influential women of the 20th Century.

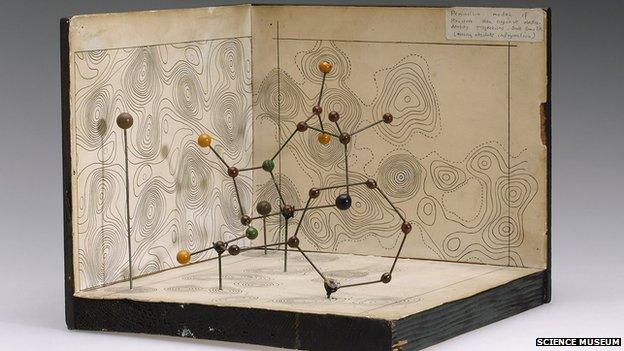

Margaret Thatcher arrived at Oxford in 1943

Dorothy Hodgkin's model of the Penicillin molecule was made during the future prime minister's time at the university

Though Margaret Thatcher's legacy is all around us, it could be argued Dorothy, in mapping the structures of Vitamin B12, penicillin and insulin, three molecules essential for human well-being, did even more to change the world than her pupil.

She also played a major role in the future prime minster's development.

When 18-year-old Margaret Roberts arrived at Oxford in 1943 to study chemistry she had never left Grantham for more than a few days at a time.

Hodgkin was already a figure of international renown, mixing with scientists and thinkers like Bertrand Russell and Isaiah Berlin. But she was only 15 years older than Margaret and, unlike many of the women tutors, she was married with young children.

She mixed with pioneering women politicians like Eleanor Rathbone and took an active interest in politics - though she supported Labour.

Who was Dorothy Hodgkin?

Born in Cairo in 1910, she studied at Oxford and Cambridge, later working to determine the structures of penicillin, insulin, and vitamin B12.

She won the Nobel Prize for Chemistry in 1964 for her work on "determinations by X-ray techniques of the structures of important biochemical substances".

From 1976 to 1988 she chaired the Pugwash movement, which warned of the dangers of nuclear technology.

A Labour supporter, she died in 1994.

In those days Somerville, like all Oxford colleges, was single-sex. But wartime Oxford had advantages for women. Though there were many privations, with so many men away at the war it was perhaps the first time they could play a fully equal role in the life of the institution.

When Margaret joined the Conservative Association, a woman politician could have few mentors. For four years Dorothy was perhaps the most significant adult in Margaret's life. She watched her develop from plump teenager to confident young woman.

Dorothy also helped Margaret. Thanks to Dorothy's efforts she received some financial support from the college.

When she came to lunch at the Hodgkin house in north Oxford, she might meet anyone from a Nobel Prize-winning scientist, to a communist organiser, or a future African leader.

She could take from her the example of a working woman with children, who was seen as the intellectual equal or better of her male colleagues.

Margaret could also observe that a successful marriage can take many different forms and how to reconcile domestic and professional issues. These things we take for granted now but then they were rare in Oxford, let alone Grantham.

Tom Hodgkin, a member of the Communist Party, was largely away teaching in the Lake District and Dorothy had responsibilities not only to her children and her students, but to her research.

She was part of the Oxford team working on penicillin, where her role was to find its molecular structure, which in those days involved enormous amounts of calibration and calculation in three dimensions, all without the aid of a computer.

Here too Dorothy was a pioneer, one of the first scientists in Britain to use computers in her research. The work that could take her decades can now be done in an afternoon.

Margaret spent her fourth year working in Dorothy's lab on a crystal of the molecule Gramicidin S, which had been grown in the Soviet Union and sent to Dorothy for analysis.

In 1947 Margaret graduated and took her first job in a plastics factory in Manningtree, Essex.

In the same year Dorothy was elected Fellow of the Royal Society (FRS). A friend wrote to her that "if a woman FRS can have three children then 'anyone can do anything'".

In style they were completely different. Margaret was brash and confrontational; Dorothy was softly spoken. Margaret was stylish and loved new clothes, while Dorothy kept the same dresses for 20 years.

Politically they were worlds apart. Dorothy was banned from the US for her closeness to the Communist Party and later took trips to China and Vietnam, playing a leading role in maintaining links with Chinese scientists and attending a dinner in the presence of Ho Chi Minh and Mao Zedong. She was an active member of CND and was awarded the Order of Lenin.

But they stayed friends. When Margaret became prime minister she had a picture of her former teacher in 10 Downing Street.

She received Dorothy at Chequers, where she pleaded for nuclear disarmament in her role as president of the Pugwash group of concerned scientists from all over the world, including behind the Iron Curtain.

Whenever they met they greeted each other warmly, though Margaret was always a little in awe of her. Even when prime minister she apparently revised for days before Dorothy's visits, as she had done for her tutorials.

Margaret was proud of her connection to Dorothy, speaking of it at meetings she addressed at the Royal Society of Chemistry, and the Royal Society (where she was one of the first leaders to speak out on global warming).

It's a peculiar fact that the UK's Margaret Thatcher and Germany's Angela Merkel both studied science at university, yet no male leader of either country has had a science degree.

What did these women get from studying science that men in politics didn't need? Scientists, like politicians, must be ready to put up with long periods of failure on their way to their goal.

Success in both pursuits also depends on a fair amount of luck. But the stubborn facts scientists deal with don't discriminate on gender.

When Dorothy was working on the B12 molecule she had to work out how more than 100 atoms fitted together in a hugely complicated three-dimensional jigsaw puzzle and she could only see the shadows of the pieces she had to fit together.

Margaret knew this kind of imagination was a gift she didn't have. But she admired those who did, and remained captivated by the magic of scientific investigation.

When she went to the Soviet Union for the first time after meeting Mikhail Gorbachev she visited the Institute of Crystallography - and sent Dorothy the pictures of her visit.

Their relationship continues to inspire. When welcoming students to the college now, Dr Alice Prochoska, Principal of Somerville, uses the story of Margaret and Dorothy as a parable - telling how the two managed to listen to each other with respect, despite their differences.

The Chemistry Between Them is the Afternoon Play on BBC Radio 4 at 14:15 BST on Wednesday 20 August.