The road to the Manchester Arena bombing

- Published

A CCTV image of Salman Abedi seconds before the bomb detonated

The Manchester Arena suicide bombing, an attack lasting only a moment, was the endpoint of a lengthy conspiracy.

At 22:30 on 22 May 2017, in a large foyer filling with people after an Ariana Grande concert, the attacker emerged from a stairway, crossed the concourse and detonated his device.

Of those he walked among, 22 were killed: children, teenagers, parents.

They included students, a nurse, a police officer, a support worker for those with special needs, and a school receptionist.

They came from different parts of the UK and diverse backgrounds, each with their own reason for being there.

Saffie Roussos, aged only eight, had attended the concert with her mother and sister.

Olivia Campbell-Hardy, 15, had attended with a friend, as had 14-year-old Nell Jones. So too had Eilidh Macleod, also 14.

Liam Curry and Chloe Rutherford, from South Shields, were teenage sweethearts out for the night together.

Sorrell Leczkowski, 14, was in the foyer, along with her mother and grandmother, to meet her sister.

Top (left to right): Lisa Lees, Alison Howe, Georgina Callender, Kelly Brewster, John Atkinson, Jane Tweddle, Marcin Klis, Eilidh MacLeod - Middle (left to right): Angelika Klis, Courtney Boyle, Saffie Roussos, Olivia Campbell-Hardy, Martyn Hett, Michelle Kiss, Philip Tron, Elaine McIver - Bottom (left to right): Wendy Fawell, Chloe Rutherford, Liam Allen-Curry, Sorrell Leczkowski, Megan Hurley, Nell Jones

Alison Howe and Lisa Lees, from Oldham, were friends waiting together to collect their children, just like Marcin and Angelika Klis, a couple from York there to meet their daughters.

Michelle Kiss was present for the same reason, while Wendy Fawell had taken her teenage daughter and others to the concert.

Elaine McIver, the police officer, was at the arena with her partner waiting to collect his daughter and her friend.

Jane Tweddle, from Blackpool, was there to accompany a friend whose daughter was at the event.

Kelly Brewster, from Sheffield, had attended the concert with her sister and niece.

Philip Tron, from Gateshead, was there with his partner's daughter, 19-year-old student Courtney Boyle.

Georgina Callander, 18, from Preston, was also a student.

John Atkinson, 28, from Manchester, was there socialising, as was 29-year-old Martyn Hett, from Stockport.

Megan Hurley, 15, lived in Liverpool and attended the concert with her older brother, who survived but suffered very serious injuries.

Many others were also seriously injured.

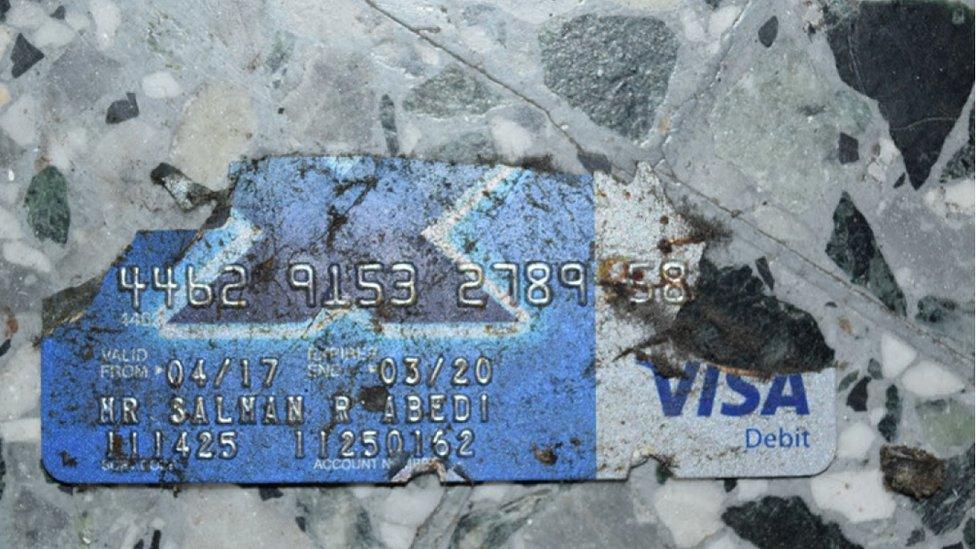

Salman Abedi's debit card, found at Manchester Arena after the attack

Planning an atrocity

The conspiracy that destroyed so many lives involved two siblings: Salman Abedi, the suicide bomber himself, and his younger brother Hashem, who was in Libya at the time of the attack.

Working in tandem, the Manchester-born pair spent months preparing the atrocity.

In the immediate aftermath, the official terror threat level was raised to its maximum, amid fears a bomb maker could be at large, and senior police spoke of a "network" when discussing the multiple arrests that took place in the UK, none of which later resulted in charges.

What emerged during the lengthy police investigation was more prosaic and arguably more troubling.

Salman and Hashem Abedi, two of six siblings, grew up in Manchester, the children of parents who had fled Col Gaddafi's Libya in the 1990s.

Ramadan, their father, was a political radical who associated with members of the Libyan Islamic Fighting Group, which was banned as a terrorist organisation and regarded as an al-Qaeda affiliate.

When civil war broke out in 2011, his sons were removed from school and taken to Libya - thus exposing them to weapons and violence in the process, as they delivered aid to rebels fighting the Gaddafi regime.

Salman would later return to school, completing his GCSEs, and Hashem would eventually enrol on a college course.

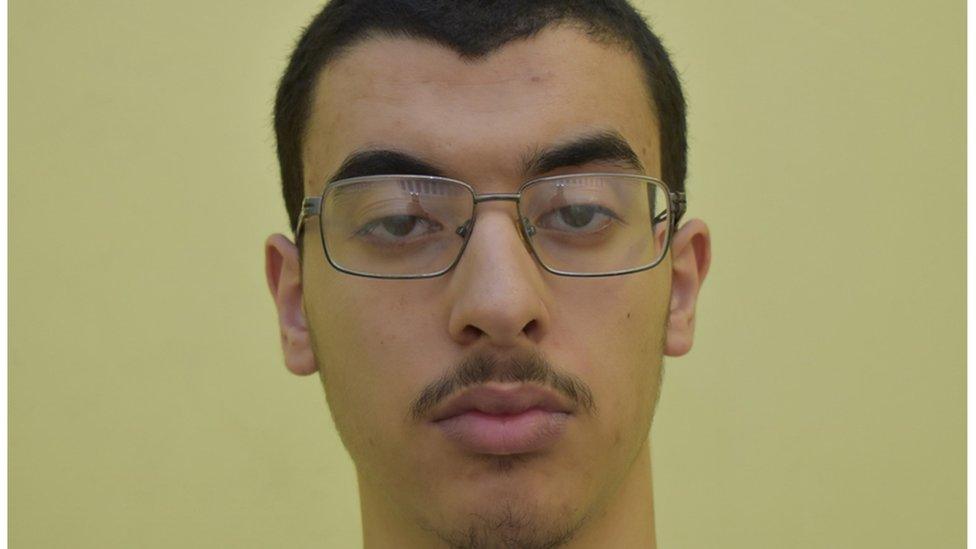

An image of a young Hashem Abedi from his father's Facebook page

Photos from the time show a youthful Hashem and his elder brother Ismael brandishing large firearms.

Ramadan, his wife and their youngest children eventually based themselves in Libya, although hundreds of pounds in benefits and tax credits were still paid into her UK bank account each month, money that Salman and Hashem used during their attack planning.

Drugs, alcohol and Islamism

The two brothers, although travelling between the two countries, lived together at the former family home in Elsmore Road, with their eldest brother having got married and moved elsewhere in the city.

Both were involved in gang culture and drug-taking, with Salman regarded as an aggressive, vindictive figure.

In time, their ease with this lifestyle would augment their commitment to terrorism, providing the context for what was to come.

After a pilgrimage to Saudi Arabia in 2015 they both became more overtly religious, but their commitment was to Islamist Jihadist violence rather than any benign expression of faith.

Salman, in particular, began openly identifying with the violent revolutionary aims of the self-styled Islamic State group, which was then at the height of its influence in Syria - and claiming to its followers to be the true path of believers - killing anyone, including Muslims, who stood in its way.

He was briefly investigated by the security service MI5, before being discounted as a threat, but he continued to appear as a contact of other extremists and the authorities received reports about his pro-IS mindset.

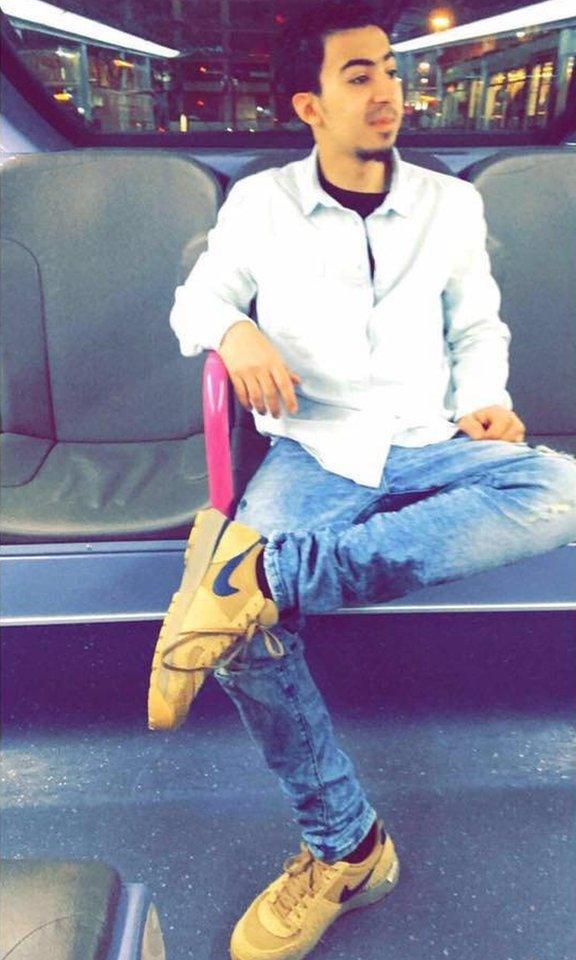

Hashem (left) helped his brother Salman Abedi prepare the attack

Hashem, although a regular at local mosques who lectured others on what constituted being a Muslim, carried on using drugs, drinking alcohol and partying with his friends.

In summer 2016, having dropped out of college, Hashem moved to Germany to work at a property business owned by Mohammed Benhammedi - a man once sanctioned by the United Nations for financing the Libyan Islamic Fighting Group - but had returned to Manchester by the following January.

It was at this point that the brothers actively embarked on their plot, renting a flat at Somerton Court in the Blackley area of Manchester, which they used over the following weeks to make the explosive TATP.

Hashem Abedi after his arrest on UK soil in July 2019

The pair are believed to have followed instructions from an IS video, then accessible online, although they might also have gained relevant expertise in Libya.

Hashem began asking people known to him to buy chemicals with their Amazon accounts in order to avoid the multiple purchases being traced directly back to the brothers.

When requesting some purchases of sulphuric acid, Hashem claimed the chemical was needed to fill a car battery or a generator in Libya, but he lacked the necessary money and therefore needed a favour.

Some people, including Hashem's contacts in Germany, refused to make the suspicious purchases.

Others attempted to do so, but the purchases were declined due to a lack of funds in their own accounts.

Some of the men provided accounts to police that led to them ultimately appearing as prosecution witnesses in Hashem's trial.

Several other associates appeared in the evidence, but were not called as witnesses.

The online shoppers

One man, Yahya Werfalli from Manchester, provided his debit card details to Hashem, asking him "When u doing this Amazon thing", only to call his bank within hours claiming he knew nothing about pending transactions relating to the website.

The details of Zuhir Nassrat, a friend of Hashem, were used in attempts to buy hydrogen peroxide, with one of them made from his home address.

Last year, Nassrat pleaded guilty to offences of perverting the course of justice, drinking and driving, and driving without a licence or without insurance. He had earlier provided his own brother's personal details in an attempt to evade responsibility when his vehicle was stopped after he was spotted driving erratically. He has since moved to Libya.

Mohammed Soliman knew both Abedi brothers

Mohammed Soliman, who was employed at a takeaway where Hashem was also working, purchased 10 litres of sulphuric acid using his own Amazon account and bank details.

He knew both Abedi brothers - and his relevant online activity was preceded, and followed by, contact with them.

Soliman, who grew up in Libya, was stopped by counter-terrorism police at Manchester Airport on 23 March 2017 as he attempted to leave the UK.

His mobile was seized and the contents were downloaded as part of that stop, but he left for Libya the following month and has not returned.

The information found on his phone later formed part of the evidence at Hashem's trial.

Werfalli, Nassrat and Soliman all had money deposited in their bank accounts by Hashem but the evidence in the case did not indicate if they knew or had any suspicion about what the brothers were plotting.

Takeaway bomb parts

Hashem even used his role as a takeaway delivery driver to obtain large empty cans of oil and sauce which the brothers then cut-up and manipulated to make bomb parts.

He also created a Gmail address to make chemical purchases, whose title, Bedab7jeana, translates from Arabic as "we come to slaughter" and is the slogan of Katibat al-Battar al-Libi, an IS-linked militant group operating in Syria.

Abdalraouf Abdallah was serving time at HMP Altcourse on Merseyside

There was direct contact with a known extremist in the UK.

The first chemical purchase of all, by a cousin who later gave evidence at trial, took place on the same day in January 2017 that Salman and two associates visited Abdalraouf Abdallah, a convicted terrorist then serving time at Altcourse prison on Merseyside.

Abdallah, seen as an influence on Salman, is confined to a wheelchair due to injuries he received fighting in Libya.

A dangerous radicaliser jailed for IS organising largely via a phone, Abdallah nevertheless had an illegal mobile in prison that he used to call Salman.

Neither the Ministry of Justice nor G4S, the private firm that runs the prison, provided a statement when the BBC asked how it was possible for a serving terrorist prisoner to obtain a phone.

Police images shows the brothers driving in Manchester during their preprations

In addition to the flat for making explosives, the brothers also gained access to an empty terraced house - on Lindum Street, in a different area of Manchester - which was used to order and take delivery of 55 litres of hydrogen peroxide.

Neither brother had a driving licence, yet they bought and drove three cars in the relevant period, using them to travel between the different addresses, transporting their purchases.

One car, fraudulently insured in the name of their elder brother Ismael, was involved in a crash, with the pair fleeing the scene after taking care to remove an address label from a box on the back seat.

Elyas Elmehdi was an associate of the Abedi brothers

In early April 2017 their parents returned to Manchester, intent on taking the two brothers back to Libya.

The pair made a hurried late-night effort to clean out the property where they had been making TATP, buying a cheap Nissan Micra as a form of storage, which was then parked outside the flat of an associate called Elyas Elmehdi.

Salman was out of the UK for nearly five weeks.

Just before flying back, he called Elmehdi, who then visited Abdalraouf in prison - the day before Salman's return.

Last year Elmehdi was convicted of drugs offences, which came to light following his arrest during the Arena investigation, but he could not be jailed as he had fled to Libya.

The final days

When Salman returned on 18 May 2017 he was not stopped at the airport nor subject to any scrutiny.

He went straight to the Nissan Micra, checking its contents, before renting a city centre flat in which he would make his final preparations, as well as visiting the Manchester Arena as a form of reconnaissance.

It had become the target.

Over the following days he used a taxi to transport the explosive to his new flat, before visiting various shops to buy items for his bomb, including thousands of nuts and bolts for use as shrapnel and a rucksack in which to hide the device.

A public inquiry later this year will examine any potential opportunities to prevent the attack.

An official report previously recorded that on two separate occasions in the months beforehand, MI5 received intelligence which was deemed at the time to be non-terrorist activity by Salman, but can subsequently be seen as "highly relevant to the planned attack".

On the night of 22 May he made his way to the arena, visibly weighed down by the rucksack on his back, making a final call to his family's Libyan number - almost certainly to Hashem - two hours before the attack.

At 22.30, after waiting for the concert to end, he walked amongst the crowds.

Salman Abedi bought thousands of nuts and screws to use as shrapnel in the bomb

A militia arrested Hashem Abedi in Libya the day after the attack.

Ramadan Abedi and Mohammed Soliman have also been questioned in the country, but both are now free.

British investigators want to speak to Ramadan and say there are still outstanding matters in the UK, although the inquiry has done as much as it can based on the available information.

It is also understood that one individual linked to the investigation has been stripped of their British citizenship

Hashem has not left custody since his Libyan arrest. During pre-trial legal submissions, his lawyers said he had been subjected to torture during his time in Libya

A lengthy extradition process took place, which saw him brought back to the UK last July when he was charged and sent for trial.

Detectives had built an overwhelming circumstantial case: his finger-marks were in the flat used to make TATP, all over the car in which the explosives and other relevant items were stored, and on the cans that had been cut up to create parts for a bomb.

He was involved in the chemicals purchases and present at every central moment of preparation.

It was a joint operation.

Officers had to build up a fingerprint profile using marks found on his every-day possessions, such as college books, but were only able to prove they were Hashem's on the night he returned to the UK.

At trial, he displayed no emotion and gradually withdrew from the proceedings, at first apparently staying in the cells instructing his legal team, before eventually refusing to leave prison and ordering his legal team to stop representing him.

This meant he was not in court - unlike some victims' families and survivors - when the jury returned its unanimous verdicts.

No one in an English court has ever been convicted of so many murders.

- Published17 March 2020