How coronavirus tore through Britain's ethnic minorities

- Published

Zohra Khaku: "People's support systems were taken away"

Zohra Khaku is on the frontline of the fight against coronavirus.

But rather than working on a ward, or delivering food, she and her staff are on the end of a phone line. She runs the Muslim Youth Helpline, which offers counselling for young Muslims in the UK.

She's one of many people in this country dealing with the overwhelming effect the virus has had on black and Asian communities. In a report released on Tuesday, Public Health England (PHE) acknowledged the disproportionate effect the pandemic has had on black, Asian and minority ethnic (Bame) people, including making us more likely to become critically ill, and to die.

Black people are almost four times more likely to die of Covid-19, according to the Office of National Statistics, external, while Asians are up to twice as likely to die.

Over the past few months, outreach workers like Zohra have been helping those affected by Covid-19 in our communities. The effects have been brutal - not just physical, but psychological, societal and financial. And they hint at why our communities were so vulnerable to the pandemic in the first place.

Zohra says they've had a more than 300% increase in calls, web chats and emails from distressed teens and young adults since the virus arrived in the UK - including a spike on Eid weekend.

The virus, she tells me, has led to many young people becoming isolated - including those who'd never had mental health issues before - while others are struggling with bereavement and grief, after suddenly losing parents and other loved ones.

"We've been going for 19 years, but we've never been as busy as this," she says. The helpline has had calls from young Muslims with mental health conditions, for whom Friday prayers was their only lifeline to the outside world, providing them with a vital support system and connection to their community.

"People's support systems were taken away," she says. "Because we've had Ramadan in lockdown, and people not able to go to Friday prayers, people who had depression or were isolated or lonely before all of this happened - whose only thing they would do with other human beings was once a week on a Friday - they suddenly don't have that any more either."

One call that sticks in her mind was from a 17-year-old girl whose parents had both been taken to hospital with Covid-19.

"Because her parents were in hospital she was looking after a 19-year-old sibling who was self-isolating, and a younger sibling who was severely disabled," Zohra says.

"Issue one was, 'I don't have any money left, please can you point me in the direction of a food bank because I need to be making food for my siblings.' The second thing was that she was doing her A-levels and applying for university, and this was at a time when we weren't sure what was happening with grades. She said that if one teacher in particular ends up giving her a predicted grade instead of her doing an exam, then she doesn't think she's going to get into the university she wants, because she doesn't think her teacher believes in her and is a little bit racist. So she's worried about her future.

"And the third thing was, the doctor from the ward that her mum's in called her just before she called us, and said, 'we don't think your mum's going to make it'. This girl said to us, 'the next phone call I'm expecting is to say that she's died. How do I make sure she has a Muslim burial? I'm only 17, I don't know how to do that.'

"That's just one case, and yet it's so complex. She was on nobody's radar, and if she hadn't reached out for help she'd still be in that situation on her own."

The outbreak's impact on ethnic minorities' mental health has been devastating. The Muslim Youth Helpline, Zohra says, has seen a worrying increase in calls from people saying they're considering suicide.

"We usually get one call about suicide every two weeks, but we get them every night now," Zohra says. "We had one day last week where half of our enquiries were about suicide, and there have been about three or four every night this week."

For information and support on mental health and suicide, access the BBC Action Line

The PHE report reveals, external that people living in the most deprived areas of the country are twice as likely as those living in the least deprived areas to be diagnosed with and to die of Covid-19. People of black, Asian and mixed ethnicities are all significantly more likely to live in the most deprived 10% of neighbourhoods, according to government statistics, external.

Overcrowded households are linked to this deprivation, too. Overcrowding is significantly more prevalent in lower-income households than in wealthier ones - according to one study, it affects 7% of the poorest fifth of households, as opposed to 0.5% of those in the richest fifth.

This poses additional challenges for Ursala Khan, who provides counselling specifically to Bame youths through her work at The What Centre in Dudley. Since the coronavirus outbreak began, privacy has become a huge issue, she says. Many of the teens she works with live with large families in small spaces, meaning they don't have enough privacy to talk on the phone or video-call about mental health.

Ursala Khan: "I see a lot of young people concerned about returning to school"

"Although we do offer alternatives like online counselling or phone counselling, there are still concerns for people trying to access those," Ursala says. "If someone lives in an over-crowded house, it's quite difficult for them to know if they'll have the privacy to speak to us about their mental health."

According to the English Housing Survey, carried out between 2014 and 2017, 30% of Bangladeshi households, 16% of Pakistani households and 12% of black households experienced overcrowding. This was compared with just 2% of white British households.

South Asian families in the UK are also more likely than white families to live in multi-generational households, with up to three generations of the same family living together. This means that school-age children may be living with their grandparents - something outreach workers have said most iterations of the government's guidance haven't taken into account.

Because of this, many of the teens The What Centre works with are scared of going back to school.

"I see a lot of young people concerned about returning to school or college, especially if they live with elderly family members or family members who have pre-existing health conditions," Ursala says.

Some people have been told to go into work when they haven't felt comfortable, too. Zohra gives the example of a young man who called the helpline after losing his job, after refusing to go into an office he deemed unsafe.

"We had a few cases of people saying 'I'm not sure if it's safe to go to work, but my employer's making me', and even before the lockdown we had calls about things like PPE," she says.

"Early on in the outbreak, there was one guy who said he got fired for refusing to go in… but he wrote in a few weeks later and told us: 'You know what, I have no job, but at least I'm alive - and I believe that if I'd continued going into work I wouldn't be'."

The high risk of 'essential' work

The risk is partly because of the kind of work that many black and Asian people in the UK do. South Asians are significantly more likely to work in the NHS, for example. In England nearly 21% of NHS staff are from ethnic minority backgrounds, but they only make up about 14% of the general population.

At the same time, black and Asian people are also more likely to be in insecure work - such as gig economy jobs, bogus self-employment and zero-hours contracts - than white people with the same qualifications. Many of these jobs, such as delivery drivers, taxi drivers and supermarket work, are now considered "essential".

Uber driver Rajesh Jayaseelan died in a London hospital in April

Research from the Trade Union Congress (TUC) last year found that ethnic minority workers are a third more likely to be in insecure work. A report released last month by Carnegie UK Trust, UCL and Operation Black Vote also found that Bame millennials in particular were 47% more likely to be on notoriously unstable "zero-hours" contracts.

Because of this, black and Asian people are disproportionately more likely to have been "key workers" in front-line jobs during this pandemic - whether that's caring for patients on a Covid ward, or delivering takeaways. Rajesh Jayaseelan, for example, was an Uber driver in London who died of coronavirus in April. Days before he died, he was evicted from his home and forced to sleep in his car because his landlord had deemed him high-risk, on account of his job.

Healthcare workers have also highlighted racism and workplace discrimination as major issues during the pandemic.

Last month, Birmingham Community Healthcare NHS Trust's head of equality Carol Cooper told the Nursing Times that black and Asian nurses felt they were being "targeted" for work on Covid wards - more so than their white colleagues.

"They feel that there is a bias," she told the publication. "The same bias that existed before, they are feeling is now influencing their being appointed - and they are terrified. Everybody is terrified."

Just some of the first 100 NHS workers to die with Covid-19 - 21% of NHS staff in England are from ethnic minority backgrounds

In another survey last month, carried out by ITV News, about 50% of doctors and healthcare staff who responded explicitly blamed "systemic discrimination" at work for the disproportionate number of deaths among Bame NHS staff. One in five healthcare workers said they had personally experienced racism - in response, NHS England said protecting staff was its "top priority" and that it had asked trusts to risk-assess Bame workers.

So for now it's impossible to pin down whether the higher death rate among Bame people is down to sociology or biology, Michael Hamilton from Ubele, a social enterprise working with Britain's African diaspora, tells me.

According to PHE, this is "complex", external - but in essence, it's both. Socio-economic inequality means we're more likely to catch the virus, while our biology means we're more likely to die.

The BBC's Steph Hegarty looks at connections between coronavirus and poverty

Ubele has set up a fund to help people hold memorial services for their loved ones after the crisis. It is also leading the call for a full independent, non-governmental inquiry into the deaths of black and ethnic minority people of coronavirus.

So what, in Michael's opinion, is causing us to die at higher rates than our white British counterparts? "Clearly there are multiple reasons, and I think I am personally, genuinely in a place to say at this point that I don't know," Michael says - adding that jumping to conclusions without all of the information is "the worst thing we can do".

"I think people are going to find different answers depending on their own speciality," he says. "We might find that there is some biology. The socio-economic stuff, that's my bread and butter, so I can recite that. But I want to keep looking, because I genuinely don't know - but I believe that we do have to know."

How systemic inequality affects our health

Dr Enam Haque is a GP in Manchester, but he also works with two Bame outreach groups - one that aims to educate patients, and another that works with Bame healthcare workers. He says he and his Bame colleagues have been "terrified" of the virus.

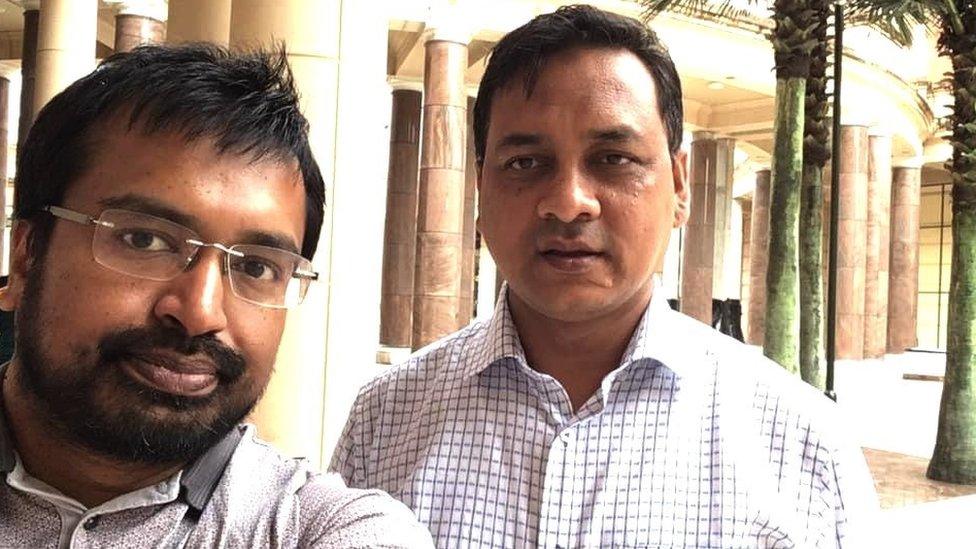

"It's quite scary as a GP from a Bangladeshi background myself, when I've seen Bame colleagues dying disproportionately," he tells me. The virus is very close to home for him - his uncle, Dr Moyeen Uddin, was a cardiologist in the city of Sylhet in Bangladesh, and was the first doctor in his country to die of Covid-19.

Dr Enam Haque (L) - his uncle, Dr Moyeen Uddin (R) died of coronavirus in Bangladesh

It's affecting his patients, too: "Many of our patients are staying away and not contacting us with health issues. My fear is that a lot of chronic conditions, lots of worrying conditions are not being diagnosed because people are scared - particularly, I've observed, from the ethnic minority population - that any kind of access to healthcare will make them exposed to Covid-19."

What about pre-existing conditions?

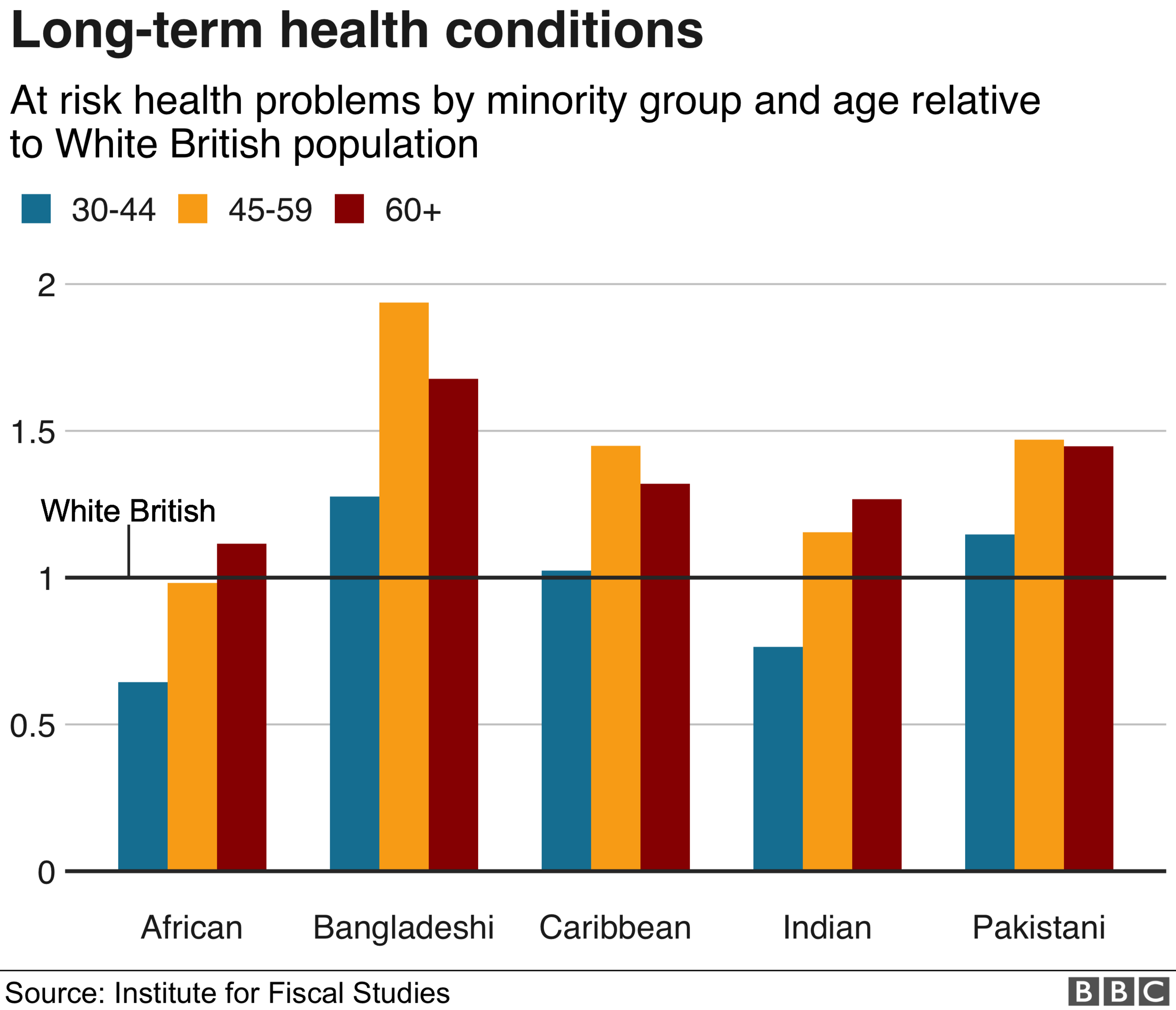

Scientists have been looking into whether certain pre-existing medical conditions could be playing a part.

Black and South Asian people are significantly more likely than white people to have Type 2 diabetes and hypertension (that is, high blood pressure), two conditions known to be high-risk.

The PHE report reveals that the proportion of both black and Asian people who've died of Covid-19 with diabetes was higher than white patients. As well as these two conditions, a recent study from Anglia Ruskin University in Cambridge has found a link between lower levels of vitamin D and higher Covid-19 mortality rates in 20 European countries. Vitamin D deficiency is particularly common among black and Asian people in the UK and other countries with limited sunshine.

I ask Dr Haque what, in his opinion, could be the reason we're so much more likely to become critically ill, or even die. He tells me that although there are medical reasons for people from Bame backgrounds to be more vulnerable, biology doesn't explain everything.

"It's a fact that people from Bame backgrounds, particularly from South Asia, are more likely to have diabetes, heart disease and high blood pressure, all of which make them more at-risk," he says. "But the bigger issue, in my opinion, are the social determinants of health."

By this, he means the economic and social conditions that make some people more vulnerable to health conditions - in this case, to becoming critically ill from a deadly virus - than others.

"There's something that has disadvantaged our population and has put us at risk," Dr Haque continues. "It's the inequality in society - there's so much more deprivation, people in our communities earn lower wages, and we have more people working in frontline jobs as well.

"As well as healthcare workers we have a lot of bus drivers, taxi drivers… they may not have access to PPE in these jobs either, so they're putting themselves at risk while serving the community. That's a major factor right there."

The problem, Michael Hamilton from Ubele says, is the people we're relying on the most in this pandemic are the ones who are the most exposed - and yet, by virtue of being considered "low-skilled", they are rendered invisible.

"I think one of the things we have to do - the biggest lesson I think we have to take from this - is to look at what we value, and who we value, and how we show them value," Michael says.

"It's our ability to not value certain types of people that has allowed this to happen."

- Published24 May 2021

- Published19 June 2020

- Published28 April 2020