Coronavirus: Boris Johnson 'heartless' for not meeting bereaved families

- Published

Covid families: The PM will not look us in the eye

Campaigners representing families whose loved ones have died from coronavirus have accused Prime Minister Boris Johnson of being "heartless" in declining to meet them.

Covid-19 Bereaved Families for Justice said it wrote to Mr Johnson five times to request a meeting.

Asked by reporters about the letters, the PM said he would "of course" meet anyone bereaved by Covid-19.

But days later he wrote to the group to say he was "unable" to meet them.

The group, which says it represents 1,600 families, said it was "devastated" to receive the letter, which it has made public, external.

Jo Goodman, co-founder of Covid-19 Bereaved Families for Justice, said: "The prime minister has done a 360 - dodging five letters, then agreeing on live TV to meet with us, and now quietly telling us he's too busy. It's heartless.

"Of course we know the prime minister can't meet every bereaved person, but we really feel he should be meeting one of the largest groups of bereaved families in the country."

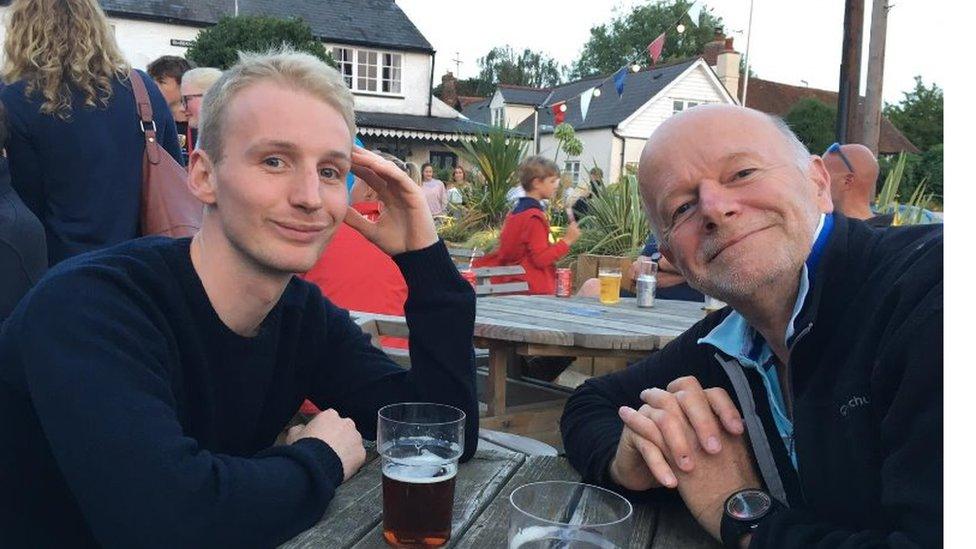

Ms Goodman, who lost her father Stuart to the virus, added: "It feels like we're the wrong type of bereaved people - like the prime minister only wants to meet with people who will smile and not ask difficult questions."

Labour said refusing to meet the group was "a new low" for Mr Johnson.

A Downing Street spokesperson said the PM remained committed to meeting people who have been bereaved as a result of Covid-19, and that he was "resolute in his determination to beat this virus" to prevent further "dreadful loss".

Bereaved relatives call for inquiry: "It wasn't good enough for our loved ones"

Covid-19 Bereaved Families for Justice is calling for an independent, judge-led, statutory public inquiry into coronavirus deaths, which it wants to begin imminently.

Unlike other inquiries, a statutory public inquiry has the power to subpoena people and take evidence under oath.

In a TV interview on 26 August, Mr Johnson was asked about the group's claim to have written to him five times to request a meeting.

Mr Johnson said he was not aware of the letters but that he would meet with "anybody" who has lost a loved one to the virus.

"I will write back to every letter we get and of course I will meet anybody… the bereaved who've suffered from Covid. Of course I'll do that," he said.

The PM said last week he would "meet anybody" bereaved due to Covid-19

In a letter from 29 August, published by the group, the prime minister offered his "sincere condolences to all the families who have lost loved ones".

But he added: "As much as I would wish to be able to offer my condolences in person to all those who have suffered loss, that is regrettably not possible and so I am unable to meet with you and members of Bereaved Families for Justice."

Mr Johnson went on to say there would be an "independent inquiry at the appropriate time", and that as the campaign group has instructed solicitors, any further correspondence relating to an inquiry "should pass through the respective legal teams."

In July the prime minister committed to an independent inquiry into the pandemic, but has repeatedly said now was not the right time.

Labour's shadow cabinet minister, Rachel Reeves, condemned the PM for not meeting the family, saying: "For him to privately go back on his public word and refuse [is] astounding, and upsetting for so many whose families and lives have been impacted by Covid in this way.

"41,504 people have tragically lost their lives to this virus. The very least the prime minister could do is respond truthfully to their families, and have the heart to meet some of them and their representatives."

What could an inquiry look like?

Independent inquiries can take many forms - from full public inquiries that can take years, or in some cases decades, and cost millions of pounds; to smaller scale, more fleet-footed investigations.

The idea is to hold the powerful to account and try to learn lessons from decisions that have gone wrong, and how to avoid repeating scandals and tragic events in the future.

Recent examples of judge-led inquiries include the Leveson inquiry into media standards, or the ongoing inquiry into the Grenfell Tower catastrophe.

Other inquiries, such as 2009 Iraq inquiry, headed by a retired senior civil servant Sir John Chilcot, do not take evidence under oath.

The government of the day is normally expected to adopt many, if not all, of the recommendations of an official inquiry, although it does not always work out like that in practice.

WILL COVID-19 CHANGE THE WORLD OF WORK FOR GOOD?: Is working from home a long-term solution?

"WE'RE ALL STRONGER THAN WE THINK": What are the positives of 2020?

- Published12 June 2020