Covid: What the tier rules say about the split between science and politics

- Published

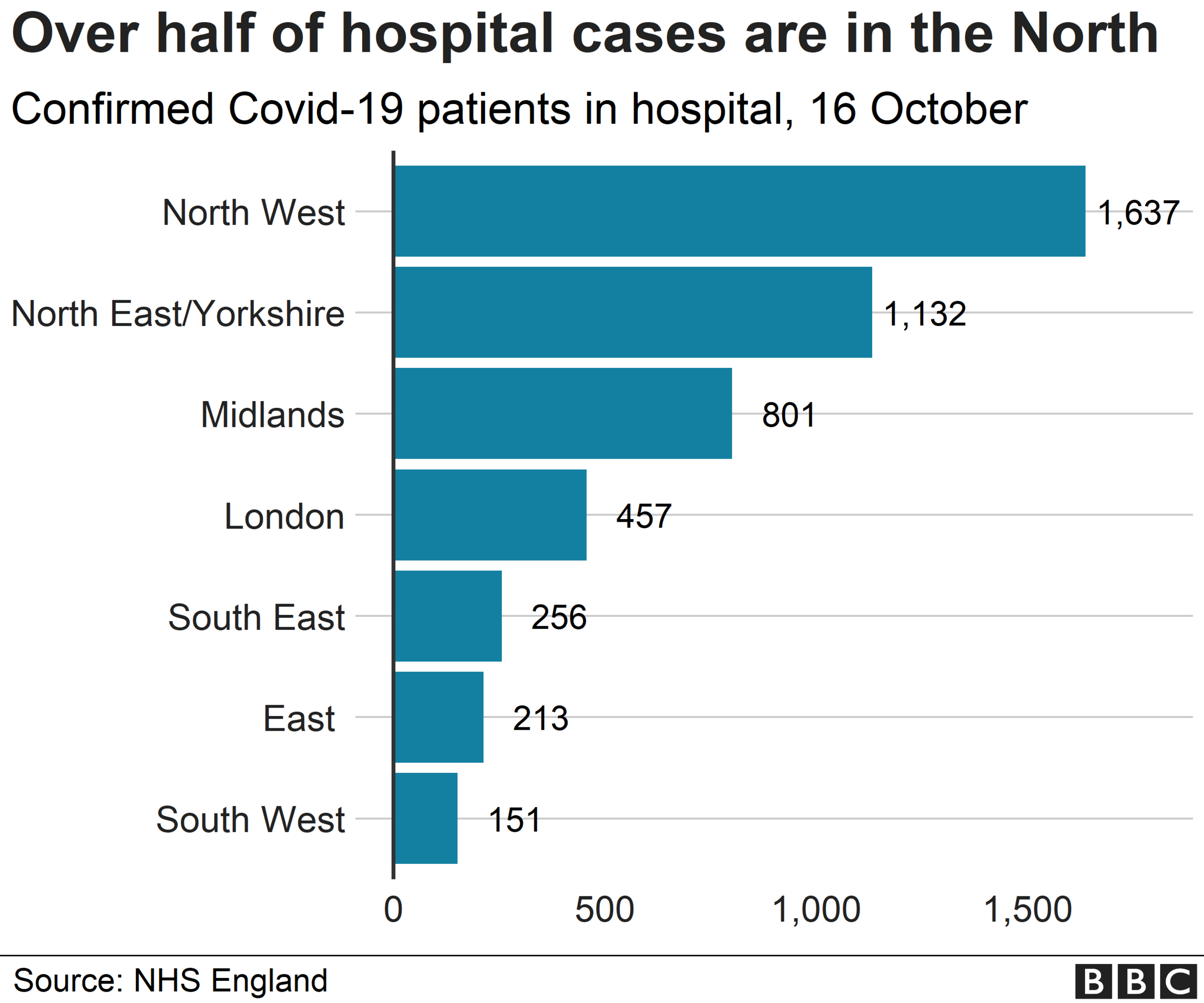

Manchester has resisted being put into the "very high risk" tier

Early in the pandemic, the government consistently said it was "following the science" - but what does that really mean, and is the divergence between politics and science now wider than it has ever been?

Some with heels clacking on the cobbles, others capturing the moment on their phones - it's like the aftermath of a big win in the football, or the Saturday after pay day. The videos show Concert Square in Liverpool heaving with crowds.

And this in a city on the crest of a second wave of coronavirus, where almost all the intensive care beds in the hospitals are full.

It was Tuesday night, hours away from the Liverpool City Region entering the toughest restrictions in the country. But the footage sparked anger, and on Twitter there was a fight over the damage to the city's reputation.

Crowds gather in Liverpool on eve of new Covid rules

Dozens of tweets insisted that those present must have been students, that no true Liverpudlian would set foot in Concert Square, let alone behave like that. The tweeters were adamant - these people came from outside.

The mayor and the metro mayor condemned the scenes - but that wasn't the only thing they were angry about.

They accused the government at Westminster of not providing enough financial support - workers affected by the closure of businesses such as bars and gyms will only get two-thirds of their wages.

On the first day of lockdown, one gym owner showed his defiance by remaining open and was fined for it.

Gyms have indeed provided a source of confusion. Liverpool mayor Joe Anderson questioned why gyms in the Liverpool City Region had to close when the area moved into tier three - very high alert - but those in Lancashire, which went into tier three on Saturday, were allowed to stay open.

Liverpool was the first place in England to go into the strictest measures

In Blackburn, with 438 cases per 100,000 (in the week to 13 October), you can work out, but in Wirral, with 284 cases per 100,000, you can't.

Prime Minister Boris Johnson has acknowledged inconsistencies. "There are anomalies, that's inevitably going to happen in a complex campaign against a pandemic like this."

But do these discrepancies encourage those who feel the government's decision-making sometimes veers away from the science?

"Following the science" was a phrase we heard a lot of earlier in the year. It's what, we were repeatedly told, the government at Westminster was doing.

Liverpool pub worker talks emotionally about job fears

The reality was always more nuanced. There was a range of scientific views on a topic about which precious little was known at the outset, and there are still vast amounts to learn.

Added to that, from the perspective of ministers, this could never only be about scientific advice.

There was a constant swirl of broader considerations, what we might call the three Ls - lives, liberties and livelihoods. Ministers have been tussling with the three Ls from the start of the pandemic. But the divergence has never been wider than it is now.

Nick Triggle is the BBC's health correspondent @NickTriggle, external

Chris Mason is a BBC political correspondent @ChrisMasonBBC, external

Claire Hamilton is the BBC's political reporter for Merseyside @chamiltonbbc, external

The critical moment in recent weeks can be traced back to 21 September, when Sir Patrick Vallance, the UK's chief scientific adviser and Prof Chris Whitty, the UK's chief medical adviser, warned of the need for immediate action.

In a televised briefing, Sir Patrick warned cases could reach 50,000 a day by mid-October if they doubled every seven days, as had happened in recent weeks.

Chris Whitty and Patrick Vallance on 21 September

We now know that on that same day, the government's Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies (Sage) met and suggested the "immediate introduction" of a "short period of lockdown," and a series of longer term measures, including:

working from home where possible

"banning all contact within the home with members of other households"

"closure of all bars, restaurants, cafes, indoor gyms" and hairdressers

all university and college teaching moved online.

A day later, what actually happened?

The prime minister said people should work from home if they could and a 22:00 curfew for pubs and restaurants was introduced. In other words, not a lot of change.

What happened to "following the science"?

Plenty at Westminster whispered, even before we had seen the minutes from the Sage meeting, that this was a victory for those in government, like Chancellor Rishi Sunak, who worried about the pandemic's crippling economic consequences.

Mr Sunak has been consistent - warning again, just this week, of the danger of "rushing to another lockdown". He warned, instead, of the "economic emergency", touching on another of the three Ls - livelihoods.

When you speak to people in the Treasury, you get an insight into what informs this outlook.

"We have to keep an eye on the medium term. There may not be a vaccine. Listening to the scientists recently, the mood music has changed. They're more pessimistic," says one.

This is no longer about dealing with a short-term emergency, but being resilient through a medium or long-term slog of a crisis.

And that means the Treasury is well aware of what is going out - in public spending - and what is coming in, in taxes.

"There isn't the headroom there was," an insider says - a reference to the £200bn already spent.

And there is a keen awareness of the economic consequences of shutting pubs. "Our economy is comparatively very reliant on social consumption," is how it is described.

The experts know the ministers have to take into account a variety of factors. One Sage member said: "Our job is to give clear unvarnished science advice so they can do that with their eyes open."

On Tuesday, Labour leader Sir Keir Starmer advocated a short, limited lockdown - the circuit-breaker suggested by the scientific advisers.

But does Sir Keir calling for a circuit-breaker make it more or less likely to happen?

Since then, the government - to quote Foreign Secretary Dominic Raab - has been "leaning in" to its regional response for England.

Political convention says, everything else being equal, it is harder to adopt a policy advocated by your opponents than it is by independent advisers.

Then there's the last of the three Ls. Liberties.

Boris Johnson, 21 September 2020

Among the most influential Conservative backbench voices is Sir Graham Brady, who said ministers had got used to "ruling by decree" and "the British people aren't used to being treated like children".

This unease at how the pandemic has, in their view, swept away some of the checks and balances on those in power, is widely held in Parliament.

Then there's the question of geography. First there was devolution for Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland, but now we're all aware of the big English cities that have metro mayors because they are fighting back against Westminster.

According to well-placed sources, Health Secretary Matt Hancock had argued for tougher measures in private. But the need to get local leaders on board has meant the tiered system has had to leave some wriggle room for negotiation.

Ministers were stung when Middlesbrough mayor Andy Preston said he flatly rejected the restrictions that the government announced there in early October. "It was a real problem for us - it undermined the public health message and threatened to undo what we were trying to achieve," one government source said.

Steve Rotheram, Metro Mayor of the Liverpool City Region, had been asking for a lockdown circuit-breaker for at least two weeks - but he said any measures must come with a bespoke financial support package for businesses. It appears this hasn't been forthcoming.

Andy Burnham outside Manchester town hall this week

But the mayor of Greater Manchester, Andy Burnham, has gone much further than his colleague in Liverpool. On Friday, he was described as "effectively trying to hold the government over a barrel" by Mr Raab.

Mr Burnham, a former Labour cabinet minister, who lost out to Jeremy Corbyn in the 2015 Labour leadership contest, is suddenly back on the national stage. He is demanding noisily and frequently the need for more generous support for those unable to work because of tier three restrictions.

There is nervousness within the Labour Party nationally, and elsewhere in the north of England, about this stance. Some worry it imperils people's health, others that it's become "the Andy show" - as one figure put it.

The idea of "metro mayors" voted for directly by the people of the region has long been championed by the Conservatives. David Cameron was a particular fan.

Top SAGE scientist tells us the regional restriction row is dangerous

"Some Conservatives are now realising you've got to be careful what you wish for," an early advocate of them says.

"And remember this, Boris Johnson was a mayor. There is a path to Downing Street that can pass via a town hall. Perhaps Andy Burnham has realised that too."

What we are seeing is how different parts of the UK have tilted in different directions. Loyalty to region, to nation, to party. The legacies of past perceived slights and injustices. The realities of perceived injustices now.

"We owe a big thanks to George Osborne for bequeathing us this incredible standoff," a senior Conservative says about the row.

Some Conservative ministers ponder privately that - in the end - Mr Sunak will be forced to be more generous to those unable to work under tier three restrictions. They don't think it'll be politically sustainable to pay people normally on the minimum wage, less than the minimum wage, for months on end.

The rows between local and central government leaders are "very dangerous" and "very damaging to public health", according to Prof Sir Jeremy Farrar, Sage member, and director of the Wellcome Trust.

But these are not the only rows that have been taking place. Across the scientific and medical community tempers are frayed and the pandemic is taking its toll.

There is a network of committees that feed into Sage, bringing together a wide range of experts from sociologists and public health directors to epidemiologists.

Many are not paid for their advice and instead are fitting it in around their day jobs. "We do it because we care and it's our life's work," said Prof Devi Sridhar, an expert in global public health at Edinburgh University, who has been advising the Scottish government.

Talk to these experts and it is clear they are exhausted.

"The requests just keep coming in," one said. "We're fed up, especially when we hear that test-and-trace consultants are getting paid £7,000 a day, and we have to put up with MPs going on the TV telling the world we are naïve and don't live in the real world. It's demoralising."

But it is not just between politicians and scientists that disputes have developed. Rival camps of scientists are clashing. Two online petitions have now been established: the Great Barrington declaration for those who want to see controlled spread of the virus and protection of the vulnerable, and the John Snow Memorandum for those arguing for outright suppression until a vaccine is developed.

Prof Francois Balloux, director of the UCL Genetics Institute, says the toxic atmosphere that is developing is really "unhelpful".

Brought together, it has created a climate where almost every utterance or development is examined for double-meaning.

The problem facing advisers and decision-makers is two-fold. First, the nature of the virus means it is a lose-lose situation - whatever decision is taken has negative consequences either for the spread of the virus, or for the economy, education and wider health and well-being. What's more, there is not a simple binary choice of one thing or the other.

For example, much has been made in recent weeks about the need for the NHS to also focus on non-Covid work, which has taken a terrible hit during the pandemic.

Referrals for urgent cancer check-ups and the number of people starting treatment have dropped, while the amount of routine surgery being done is still half the level it was before the pandemic.

THREE TIERS: How will the system work?

SOCIAL DISTANCING: Can I give my friends a hug?

PAY-PACKET SUPPORT: What will I be paid under the new scheme?

SUPPORT BUBBLES: What are they and who can be in yours?

FACE MASKS: When do I need to wear one?

This can have tragic consequences. This week the British Heart Foundation warned the number of younger adults dying of heart disease had increased by 15% during the pandemic.

The argument put forward by some is that the government should choose to do more non-Covid work. But, and this is a point the health secretary has been making week after week, if hospitals fill up with coronavirus patients, it makes non-Covid work harder to do.

The second key issue - and this goes to the heart of the disagreements we have seen bubble up in recent weeks among the scientific and medical community - is that there are huge gaps in the evidence and knowledge.

This is true on everything from the numbers infected already and the level of immunity exposure brings to the true impact of "long Covid", and exactly what effect any restrictions beyond a full lockdown actually have.

In normal times, the scientific and medical community is able to reach more of a consensus off the back of rigorous randomised controlled trials and painstaking peer review.

But in a fast-moving pandemic with a new virus, that has simply not been possible. Paul Hunter, a professor of medicine at the University of East Anglia, says it means there is such "uncertainty in the science" that he does not think any plan is guaranteed to work.

And then there is the human factor - the unintended consequences of actions that are impossible to take into account in the modelling. Hence the prospect of scenes like the ones we saw in Liverpool, which were not taken into account by Sage in its latest advice.

But Prof Keith Neal, an infectious disease expert at Nottingham University, says it shouldn't come as a surprise that people react in the way they do. Both young and old are suffering, he says, from not being able to meet up with people. "This degree of isolation is not allowed in prisons under human rights legislation."

People from different households will not be able to drink together inside, after London went into tier two

It is, he says, therefore natural that some people will ignore the rules. Closing pubs may sound good on paper, he says, but it could lead to an increase in house parties where people are "far more at risk".

So where has this left us?

The complexity of competing interests, uncertainty in the science and general exhaustion across society both among decision-makers and the public has, some fear, left us in the worst of both worlds.

Delay and deliberation, says Sir Jeremy Farrar is a "decision in itself".

But by reaching a decision by default there is a risk - another adviser says - of making the same mistakes we made at the start of the pandemic.

"In March we toyed with the Swedish model of limited restrictions with the hope of developing immunity and then hesitated. But we then went for a lockdown, but it was introduced bit by bit and it was too late anyway.

"The same thing has happened again - we have delayed and then gone for some half measures. I can understand why. This is bloody difficult."

The government is now hoping it will be just enough that we can get through this wave without a devastating number of deaths or hospitals being overwhelmed. But it's a big risk - it could all unravel.