What is the Undercover Policing Inquiry?

- Published

The inquiry has already attracted criticism from campaigners

One of the most important public inquiries in recent years is beginning in London on Monday after years of delays - but can it get to any answers?

What is the UCPI?

The Undercover Policing Inquiry (UCPI) is one of the most complicated, expensive and delayed public inquiries in British legal history.

At its heart is a series of very serious allegations of systematic abuses by undercover policing units developed over 40 years.

It was officially set up in 2015 by the then Home Secretary Theresa May, after a series of allegations that she said amounted to evidence of "historical failings".

Who committed these failings?

There are two undercover units at the heart of the inquiry.

The first is the Metropolitan Police's Special Demonstration Squad (SDS). It had its genesis in the late 1960s when Scotland Yard began investigating groups protesting against the Vietnam War.

It evolved to run operations into a wide range of political groups, causes and movements, most of which were on the left of politics.

The second unit, the National Public Order Intelligence Unit, was a team carrying out identical work largely outside London. Both units have now been disbanded.

What are the main allegations?

Mark Kennedy: Undercover relationships

In 2010, Mark Kennedy, an undercover police officer who had spent years pretending to be an environmental campaigner and supporter of other causes, was unmasked.

Mr Kennedy had had a series of relationships with women - none of whom knew his true identity.

The following year, Kennedy's deployment was revealed to have led to miscarriages of justice and his name became widely known in public.

Twenty environmental protesters who had been accused of an alleged plan to occupy a strategically-important power station had their convictions quashed by the Court of Appeal after it became clear that evidence of an undercover operative, who had played a role in the affair, had not been disclosed to the defence.

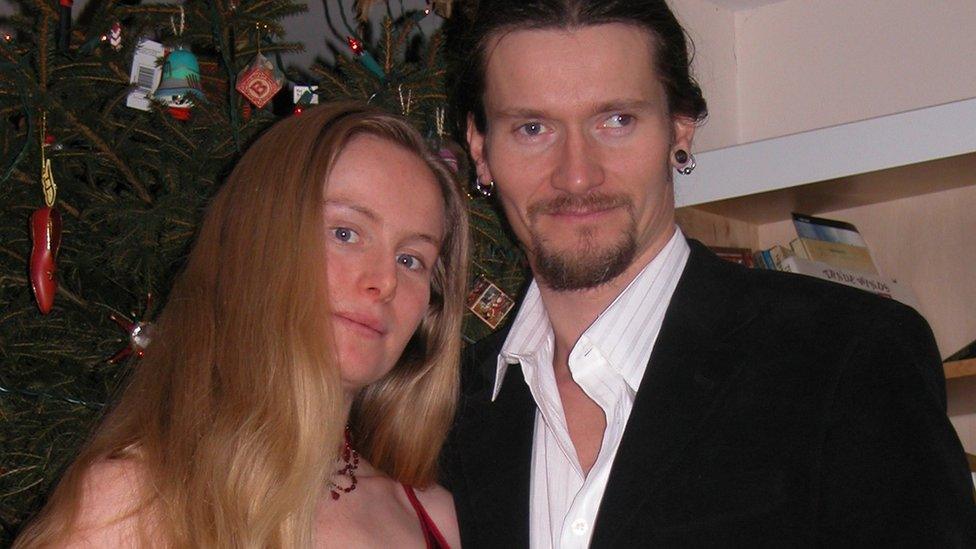

One woman, Kate Wilson, spent two years in a relationship with the officer who had a parallel real life elsewhere.

Ms Wilson's two-year long relationship with Mark Kennedy began in 2003

Another, known only as Lisa for legal reasons, was with Mr Kennedy for much longer.

"It was exactly 10 years ago that I discovered that my partner of six years was actually a policeman," says Lisa. "He was a fictional character - his identity was fabricated and he was put into my life to deceive me, by his employer, who knew that one day they would remove him."

Campaigners have identified at least 30 women who were in relationships with officers.

The earliest dates back to the 1970s - suggesting that the targeting of women may have been considered a justified means for officers to embed themselves deep into the movements they were targeting.

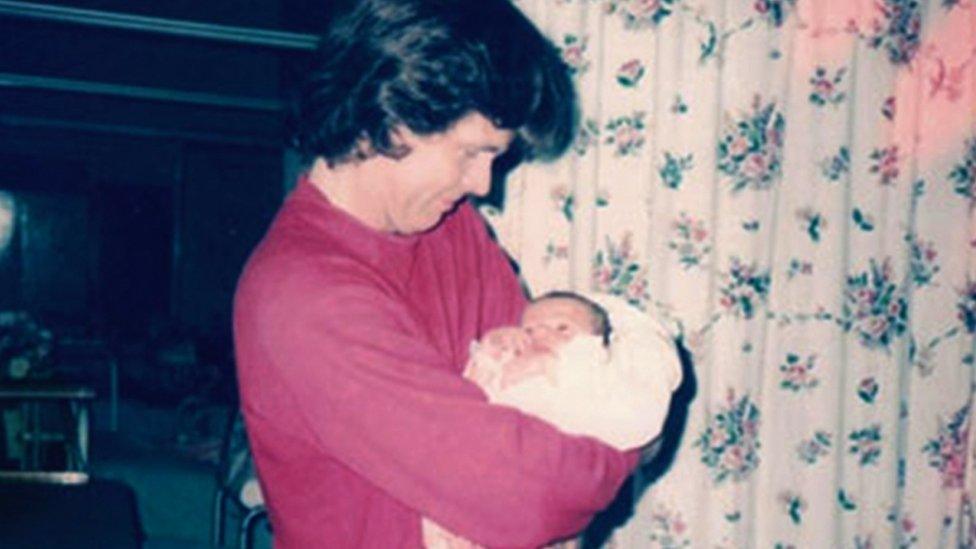

Another officer, Bob Lambert, fathered a child with his partner, an animal rights campaigner, before disappearing from her life when his deployment ended. She has since received £425,000 in damages from Scotland Yard.

The Met has already settled one case involving former officer Bob Lambert, who fathered a child

Only one former officer, Peter Francis, has voluntarily revealed himself. Mr Francis had not been in any relationships - but he'd been deployed against justice campaigns.

He revealed to the Guardian newspaper that the Metropolitan Police had gathered intelligence on the family of Stephen Lawrence, external who, at the time, were campaigning for redress for the botched investigation into the racist murder.

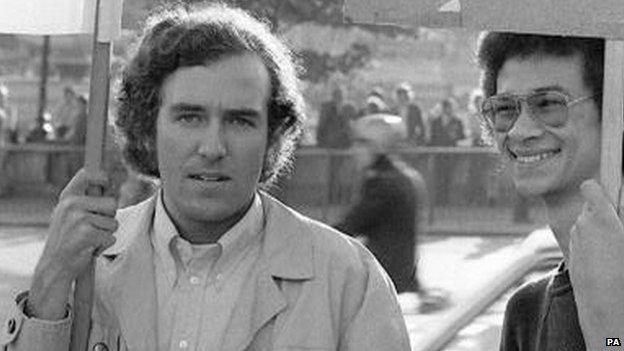

Some officers appear to have gathered intelligence on Labour MPs including Peter Hain, once a leader of the UK's anti-apartheid movement, and Jack Straw, who went on to become the home secretary.

Many officers deployed by the SDS created their undercover personas after being instructed to research records of real children who had died young - and then "resurrect" that identity for their own use.

Who are the complainants?

There are 200 "core participants" in the inquiry. They include:

Women who had relationships

Justice campaigns - including families of victims of racist murders

Political activists in left-wing groups and anti-capitalist movements

Labour politicians

Environmental protesters - including many people who have spent decades warning of climate change

Animal rights activists

Trade unionists who say they were blacklisted from taking work based on their political views

Peter, now Lord, Hain: Monitored from anti-apartheid day - and when he was an MP

What do the complainants want?

Many want to simply know why their lives were spied on and what information the police gathered on them.

It's been suggested that the undercover units gathered information on up to 1,000 different groups over 40 years - there are millions of pages in the undercover archives.

They also want to know the identities of the officers. As things stand, the vast majority are not going to be revealed in public. Some 69 fake names used by officers have been published, external - but many more remain unknown.

Mr Francis, the former officer who accused his bosses of running an operation against the Lawrence family, also wants recognition for the mental scarring that many officers live with - and transparency about who at the top of policing knew what was happening.

Have the police admitted any wrongdoing so far?

In 2015 the Metropolitan Police made an "unreserved apology" to women whom it admitted had been deceived into relationships that should never had happened - and paid out compensation.

Why has the inquiry been so delayed?

An enormous team of lawyers has spent five years working out how it can actually hear evidence because of the complicated and often competing issues relating to secrecy.

To date, it has cost almost £30m just to get to the starting point of hearing evidence.

After the November 2020 opening, it will run for at least three years as it works its way chronologically through the operations that took place.

- Published24 March 2019

- Published25 March 2015

- Published20 November 2015