'Kevin's identity was stolen by police after he died'

- Published

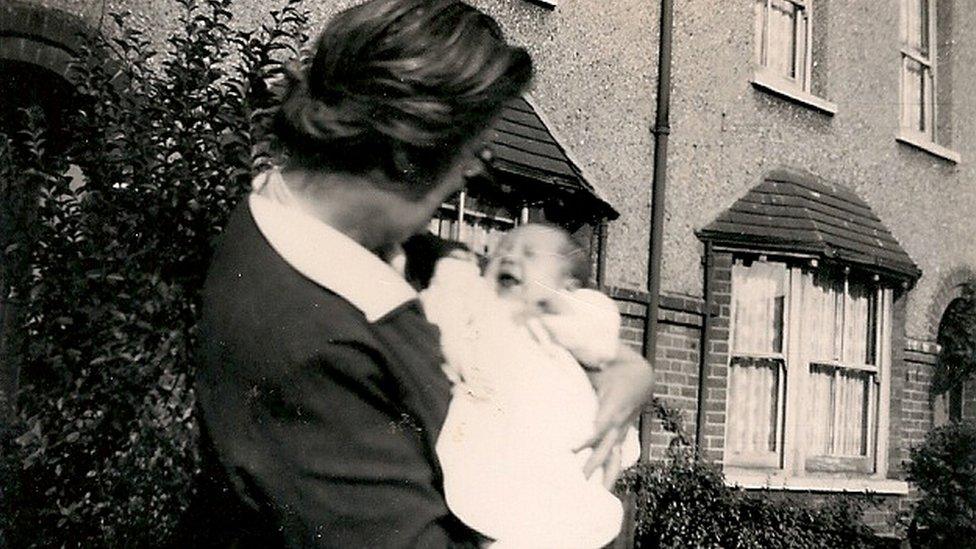

Kevin Crossland pictured with his grandmother in 1961, the year he was born

David Crossland's whole family died beside him on a holiday flight to Yugoslavia in September 1966. His wife Daphne, and their young children Kevin and Lynne were killed when their plane crashed in woods as it was approaching the airport in Ljubljana. David, who was sitting across the aisle from his wife and children, crawled to safety from the burning wreckage.

In the decades that followed, David suffered from long-term leg injuries and survivor guilt, but managed to build a new life. He remarried and had another son and daughter. He met his second wife, Liisa, when she was helping to nurse him as he recovered in hospital in London.

David died of cancer in 2001. He never knew that at that time an undercover police officer was using the name Kevin Crossland - the five-year-old son David had lost in the plane crash.

Liisa Crossland remembers her husband once telling her that he had heard from his police acquaintances that some officers would adopt the identities of dead children. It was a practice used by the assassin in the 1970s Fredrick Forsyth thriller, The Day of the Jackal, later a film.

Liisa says she has felt enormous anger for the two years since the family was first informed about the use of Kevin's name by police.

"How can someone stoop so low? My husband is not here to fight for the truth. But on behalf of him and my family, I want to get to the bottom of the way Kevin's identity was used," she said.

Liisa and David's son, Mark - whose middle name is Kevin in memory of the brother he never knew - describes it as "the most irresponsible thing the officer could have done. I really don't know how my dad would have dealt with this if he had still been alive. We are looking for a proper apology from someone who actually means it."

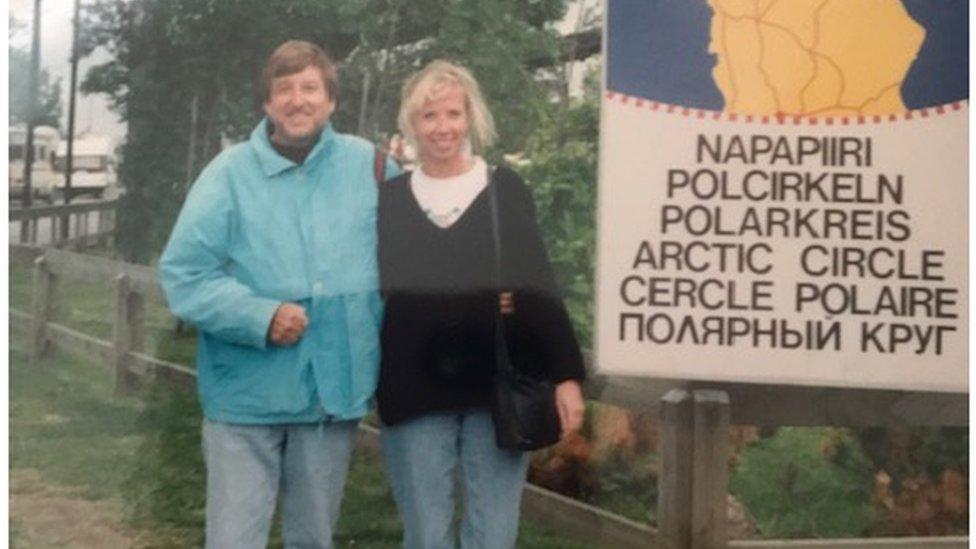

David and Liisa Crossland in 1999

The Crosslands are one of four families who have begun legal action against the Metropolitan Police over the use of their dead children's identities by undercover officers between the 1980s and early 2000s.

The other children whose identities were used were:

Rod Richardson, who died of pneumonia two days after he was born in January 1963 in hospital in south London

Neil Martin, who died a month after his sixth birthday in hospital in County Durham in October 1969. He was severely disabled

Michael Hartley, whose body was never found after he fell from a fishing trawler when he was a teenager in August 1968

The practice of taking dead children's identities has been exposed as a tactic used by police officers from two units, the Special Demonstration Squad and the National Public Order Intelligence Unit, who infiltrated protest groups and political movements over a 40-year period from 1968.

They would use the children's birth certificates to apply for passports and driving licences to allow them to build a back story or "legend".

The families of Kevin, Rod, Neil and Michael are claiming for misuse of private information, negligence and personal injury - and are calling on the Met to apologise and admit liability.

In a statement the Met said it was investigating the claims and was "unable to comment further at this time".

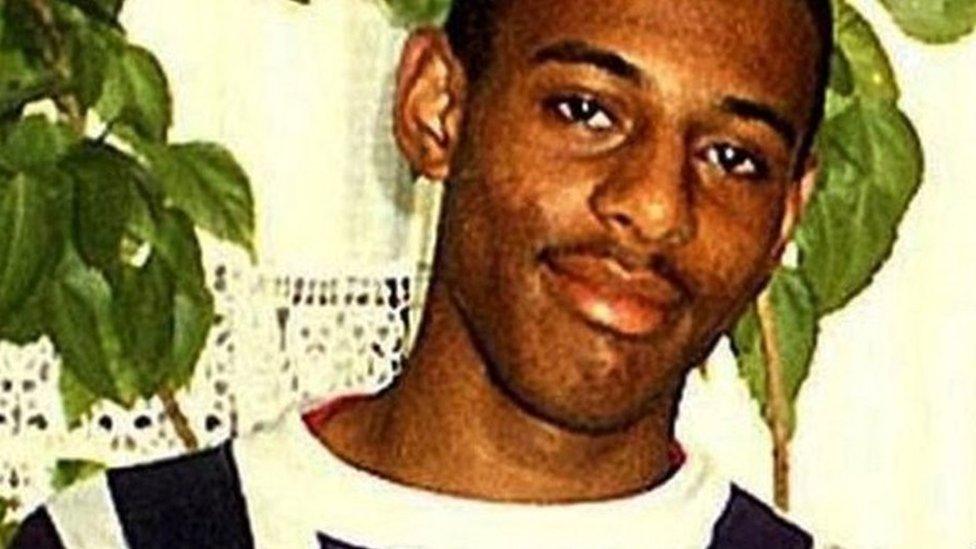

This photo of Kevin was taken not long before he was killed

It comes at the end of a year which has seen the much-delayed public inquiry into undercover policing finally get under way. It's examining the role of police spies over a 40-year period from the late 1960s.

During opening statements last month, Heather Williams QC, representing the families of Kevin, Rod, Neil and Michael, as well as other families, denounced the use of dead children's identities by officers as an "abhorrent practice".

"It has caused our clients' memories of their loved ones to be forever tarnished. The intensity of their original grief has been brought back with full force," she said.

Faith Mason‘s son, Neil, died in 1969. An undercover officer used his identity

A "tradecraft manual" for the Special Demonstration Squad (SDS) is among a cache of documents released to the inquiry. It reads: "By tradition the aspiring SDS officer's first major task was to spend hours and hours at St Catherine's House leafing through death registers in search of a name he could call his own."

And it goes on: "The SDS officer would assume squatters' rights over the unfortunate's identity for the next four years."

In some cases officers are believed to have visited the graves of children whose names they were using. They also researched their families, described in the manual as establishing their respiratory status and "if they were still breathing, where they were living".

The officers who used the identities of Kevin, Rod, Neil and Michael infiltrated groups including the Animal Liberation Front, Class War and the Revolutionary Communist Party. Their true identities, like most of their colleagues', remain secret, as do even the cover names of more than 50 other police. More than 40 officers are said to have taken the names of dead children.

The officer who used Kevin's identity did not appear to have been authorised to do this, according to a statement from the inquiry in 2018.

He had been given permission to use his second undercover name, James Straven, but not the identity of a dead child.

The inquiry has heard that he was known as James Straven when he had relationships with two female activists. This is another practice used by a number of officers which is under scrutiny by the public inquiry, which had its initial hearings last month and will resume next year.

Liisa says she is grateful for the difficult work done by the police generally, but her family is now in torment as a result of the undercover tactics.

"Kevin's memory belongs to us. He was laid to rest. Why was his identity stolen?"

- Published2 November 2020

- Published19 November 2020

- Published10 November 2020