Jeremy Bowen: 'I was wrong about this town of my childhood'

- Published

The BBC's Middle East editor Jeremy Bowen grew up in South Wales and would visit Merthyr Tydfil as a child. He returned for a series in which our reporters are revisiting areas of the UK to see the impact of Covid, and found his assumptions about the town were wrong.

Where is the love? Merthyr has plenty, despite these challenging times

I wasn't surprised when I saw that Merthyr Tydfil had, for a time in the late autumn, the highest coronavirus infection figures in the United Kingdom. It seemed to fit the profile, given the town's fixture in the Welsh government's annual survey of deprivation.

Many of the years since the death of industry in the 1980s have been hard. And social distancing has not come easily to the steep and narrow streets of the South Wales valleys.

The leader of Merthyr borough council, Kevin O'Neill, put it better than I could: "I think that's more about the nature of Welsh valley people anyway. We live in old industrial housing that's very closed - the infrastructure. You've got your pubs, you've got your Chinese, you've got your corner shop, so it's made for Covid transference.

"But also what you've got is we're very tactile… We're very close people. We're very affectionate people. You know, to tell us not to hug is criminal."

As part of the BBC's Our Lives series, Jeremy Bowen visits Merthyr Tydfil, to see the impact Covid's had on the town

Mr O'Neill, a retired detective with South Wales Police, said Merthyr had been buzzing with plans for new investment and jobs before the pandemic hit. Better times, he insists, will return once the virus is beaten. Skilled workers earned good money in the '50s and '60s.

I stood with Mr O'Neill, overlooking the town, near the gates of Thomastown Park where I used to play as a child with my brothers when we travelled up from Cardiff in the 1960s to visit my aunt and uncle.

Jeremy's father Gareth Bowen (right) with his Merthyr-born parents Winnie and Emlyn

More in the Our Lives series

In the 1930s my grandfather, Emlyn Bowen, scavenged for coal on tips. He was with crowds of other unemployed men, after he lost his job at one of the steelworks during the Great Depression.

He moved his wife Winnie and son Gareth, my father, down to Cardiff when jobs opened up at the East Moors works, continuing a migration in search of work that had started when my dad's family, on both sides, left rural Carmarthenshire for the ironworks and pits of Merthyr Tydfil.

His maternal great-grandfather, Evan Griffiths, was a "catcher" at Cyfarthfa ironworks. His job was, literally, to catch iron bars with tongs as they came out of the rolling mills.

Cyfarthfa and the other Merthyr ironworks were at the centre of the British industrial revolution in the 1790s, pioneering new technology and processes. Merthyr was a boom town, the biggest in Wales.

We’re always shown in a bad light but there are a lot of good things about Merthyr Tydfil

Chris Parry, a historian based at the Cyfarthfa Castle Museum in the old ironmaster's baronial mansion showed me the blast furnaces, which still stand, after more than two centuries.

"It would have been a scene of smoke billowing out of all these 50-foot-high furnaces, light, white, hot light beaming out of all the furnaces," said Mr Parry, as he explained how they had survived so long. They were built into a natural hill.

'I was wrong'

There were countless smaller furnaces too, he says. "It would have been overwhelming for the senses - light, smoke, smells of sulphur - and the sound as well; this overwhelming hammering and rolling of the iron."

Merthyr's self image, as a town forged the hard way, was created in that brutal industrial landscape. With it came a tradition of self-help, which this year's pandemic has brought flooding back.

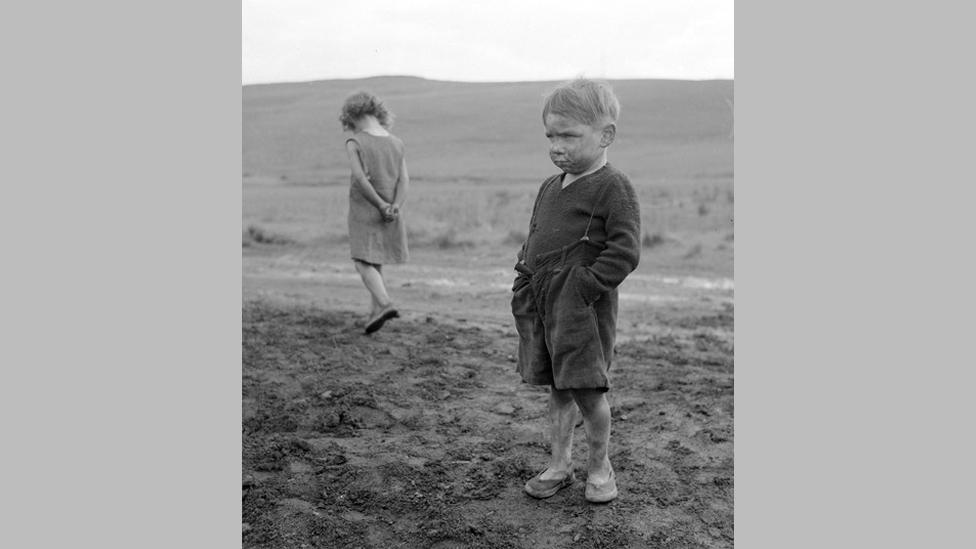

A photo of children near Merthyr in the 1950s, taken by Jeremy's mother, Jennifer Bowen

My mother, Jennifer Bowen, was a photographer on the Merthyr Express in the late 1950s.

"Don't forget," she told me, when I dropped in on her in Cardiff on my way up the valley of the river Taff, "Merthyr people are very warm. Everyone was kind to me."

But that didn't alter my assumption that the pandemic, on top of Merthyr's well-known problems, that mostly start and finish with poverty, was going to have been too much of a strain.

But I was wrong. As Merthyr has suffered, and is still suffering, its people have pushed back. The warmth and kindness my mother found in the '50s is still there.

Saviour with Greggs donation

People in Merthyr often complain about their portrayal in newspapers or on TV. On a walk with the Merthyr Ramblers, a group of mostly retired people, I asked Maureen Donovan about the way others see them.

"Always the worse. We're always the top of the table for Covid tests, bad teeth, heart attacks, obesity. And it's not all like that. [They] tar us all with the same brush I think. We're always on the media shown in a bad light. That is totally wrong, because there are a lot of good things about Merthyr Tydfil."

We have a fragile community... we try to make people feel wanted, loved, to give people purpose

My assumptions about the town's ability to cope with the pandemic were wrong.

Up the hill from my father's boyhood home on Christopher Terrace, a street of cottages built just before World War I by my great-grandfather, John Griffiths, is the Twyn Community Hub. It is run by Louise Goodman, a psychologist who has raised more than £800,000 since March to help people in all sorts of ways.

Merthyr, Louise explained, is "... a fragile town. We have a fragile community... we try to make people feel wanted, loved, we give people purpose. We try to make the best of what people have got and help them to get through a very uncertain future."

A psychologist, Louise worries about the inner world of the people she helps, which she says is "in turmoil".

"There are lots of people who don't understand what's going on. They don't understand the things they're told on the news. They don't have any clarification because there are a lot of people without the internet here… a lot of elderly."

The effect of Covid is "horrendous" and its long-term impact unknown, she says.

Homeless people have been housed by the council in flats and bed and breakfasts, to reduce their risks of coronavirus infection.

I met some of them with Claire Jones, a volunteer who started a group called Merthyr Homeless Outreach. That night Claire and her friends Pauline and Susan were picking up unsold food donated by Gregg's for the hungry. Claire couldn't stop herself hugging Maldwyn Ashton, a young man open about his drug addiction.

The warmth of the Valleys does not always sit easily with the latest versions of Covid regulations, but he had just thanked her for saving his life when he was on the streets.

The arrival of vaccinations, and mass testing which Merthyr has pioneered alongside Liverpool, might mean we are all able to think about an end to the pandemic. But the people I met in Merthyr Tydfil know their race is not yet run, let alone won.

Clockwise from top right: Mass testing in Merthyr, a Covid warning sign, an aerial view of the town