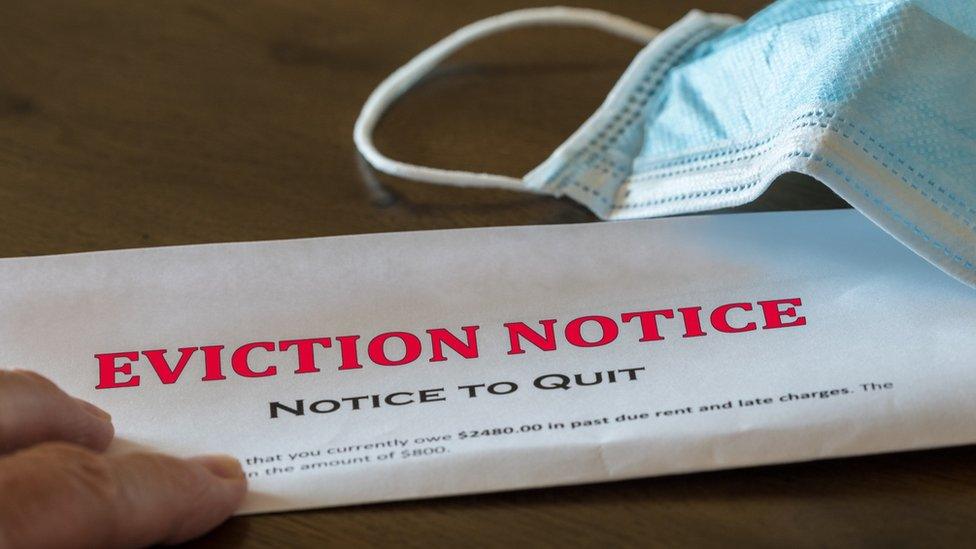

Renters: Eviction ban in England extended until March

- Published

Renters: Eviction ban in England extended until March

The ban on evictions in England is to be extended until the end of March, the government has announced.

It means eviction notices - which could have started again on 22 February - cannot be served for another six weeks.

Housing Secretary Robert Jenrick said it would ensure renters remained protected "during this difficult time".

The eviction ban had already been extended from 11 January when it was originally due to expire.

Mr Jenrick said the ban on the enforcement of evictions by bailiffs would continue "in all but the most serious cases".

He added that the government had taken unprecedented action to support renters during the Covid pandemic, and that measures had struck "the right balance between protecting tenants and enabling landlords to exercise their right to justice".

But Labour, charities and landlords groups said the measures did not go far enough.

Shadow housing secretary Thangam Debbonaire said: "Last minute decisions and half-measures from the government are putting people's homes at risk.

"Ministers promised nobody would lose their home because of coronavirus, but the current ban isn't working.

"The government should give people security in their homes, by strengthening and extending the ban for the period [virus] restrictions are in place."

Huge sums of money have been pumped into the economy to stop mass unemployment and keep the economy afloat.

But the government has stopped short of direct financial support for tenants in rent arrears, and landlords losing income.

While I'm told some within Whitehall are receptive to the idea of emergency grants or loans, the policy has met significant resistance - and there's little sign Westminster will follow Wales and Scotland's lead.

But there is concern from groups representing tenants and landlords that a rent debt crisis is mounting - which will, in the end, see many people forced from their homes.

Mortgage holidays and mediation have helped many get by for the time being - but some argue that a longer-term policy is needed.

Banning evictions for another six weeks may bring some temporary relief, but as one frustrated Conservative MP put it to me: "This can't go on forever."

Shelter said its research showed almost 445,000 private renting adults in England had fallen behind on their rent or been served with some kind of eviction notice in the last month.

The housing and homelessness charity's chief executive Polly Neate said the extension would "keep people safe for now", but warned it was "not an answer to the evictions crisis".

"Renters are still are being served with eviction notices every day and our helpline is flooded with calls from those desperately worried about paying their rent," she said.

"Before the ban is lifted, the government must give renters a real way out of debt. That means a lifeline of emergency grants to help pay off 'Covid arrears' so people can avoid the terrifying risk of eviction altogether."

Meanwhile, National Residential Landlords Association chief executive Ben Beadle warned the announcement was storing up future problems.

He said 800,000 private renters had built up arrears since the ban came into force, which they would struggle to ever pay off.

"It will lead eventually to them having to leave their home and face serious damage to their credit scores," he said, as he called for further financial support to combat "the debt crisis renters and landlords are now facing".

Housing is a devolved issue, and Wales and Scotland have already extended their bans to the end of March.

In Northern Ireland, landlords are required to give tenants 12 weeks' notice to quit, before moving to eviction proceedings. The rules were extended to March in anticipation of the second wave of the Covid pandemic.

Evictions were first banned at the start of the first lockdown in March, with ministers also extending the notice period landlords must give tenants to end their tenancy from three to six months.

Courts began to clear the backlog of repossession cases in September, starting with the most serious cases, such as those involving domestic violence or anti-social behaviour.

But the housing secretary then called a so-called "Christmas truce", meaning bailiffs were not allowed to enforce possession orders between 11 December and 11 January.

JESY NELSON 'ODD ONE OUT': Jesy opens up about cyberbullying abuse and the effect it's had on her mental health

'Man Up': Honest conversations about what it's like to be a man today

Related topics

- Published8 January 2021

- Published21 September 2020

- Published10 September 2020