Is four years too long to wait for justice?

- Published

Four years to wait for her day in court: Jenny's story sounds extreme - but not exceptional

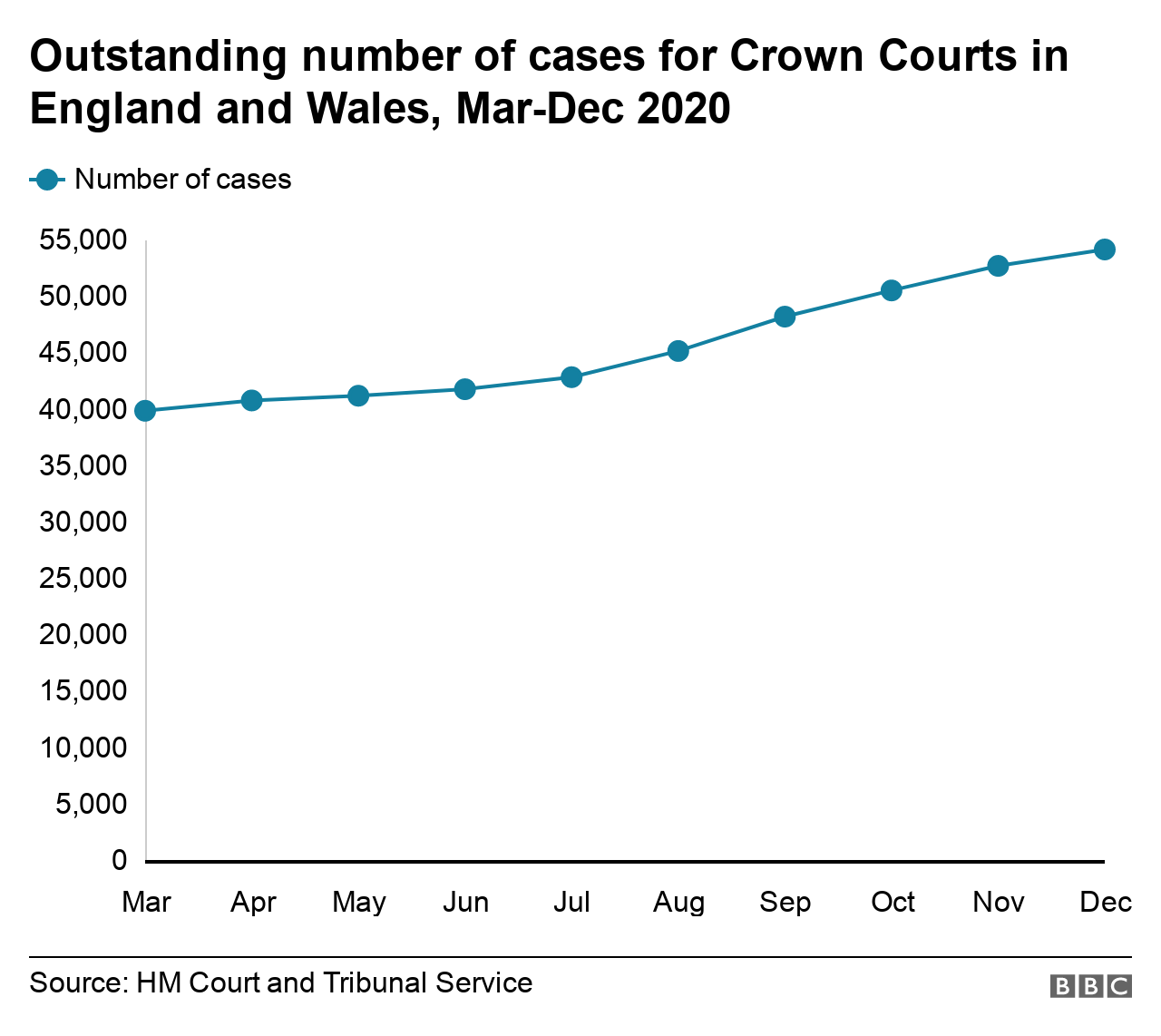

The backlog in the Crown Courts has hit a record of 56,000 cases - meaning some cases are now being timetabled for 2023. The Lord Chancellor and Justice Secretary Robert Buckland - the cabinet minister in charge of the courts - is promising that a recovery plan will bring justice. But will those plans make a difference to victims waiting for their voices to be heard?

If you want to know what it feels like to wait for justice for a serious crime, consider the limbo that "Jenny" finds herself in.

For legal reasons, the BBC is not revealing any details of the case but, put briefly, she quietly and secretly coped for years with having been the victim of serious sexual violence. When the #MeToo movement took hold, she decided that she too had to speak out.

In 2018 detectives video-recorded Jenny's allegations and, after a long and complex investigation, the Crown Prosecution Service concluded last summer that her abuser should be charged with serious offences.

Jenny agreed not to begin deep trauma therapy because it may affect her evidence in court.

Last autumn, she learned when her abuser would face trial - and she was devastated.

Weeping, she recalled her conversation with the police officer.

"The first court hearing and second court hearing were really close to each other. And so that gave me some faith, I thought it's taken this long to get to this point. But actually, maybe this next bit isn't going to be as long.

"I was asked... to provide dates of availability for court for the next nine months. So I thought, it's just another nine months. I can do this. And then I got the call - and they gave me the date. It was 2022.

"I said down the phone, 'You do mean 2021?' And they said, 'No, we mean, 2022.' And I got really angry. How can anyone believe that that is acceptable that you keep somebody in trauma and you don't give them the access [to the therapy] that they need?"

Every week since has been a rollercoaster - to the point that Jenny cannot currently work and her family are rallying around to support her as she tries to comprehend the absence of justice.

"I start having a panic attack in the middle of town, I can't breathe. My body goes tight. I start convulsing, I'm sometimes sick, I'm shaking, I'm wailing. Trying to understand, why is that happening?

"There have been two occasions where I felt suicidal. The second time was when I was told the trial would be 2022.

"I felt like I'd been let down by the state. This was the whole system letting me down."

Jenny 's experience sounds extreme - but it is not exceptional, because of the enormous delays in criminal justice.

Record backlog

Last month the watchdogs that report on the police, prosecution, prisons and probation all agreed that the backlog in Crown Courts of 54,000 cases was of grave concern.

In the last week, it's hit an all-time record of 56,000.

There was a backlog in the Crown Courts before the pandemic hit. Coronavirus made operations far harder because many courtrooms are too small to safely distance everyone who needs to be inside.

Speaking to the BBC, Mr Buckland has defended the government's attempts to tackle these record backlogs. He has promised that his court recovery plan will work - but it will take time.

Today, he's announcing 14 more temporary "Nightingale Courts" - converted spaces and hotel conference facilities that are part of £113m of spending to alleviate the pressure.

Part of Manchester Crown Court will be knocked through to create a new "super court" for large socially-distanced gang trials. About 20,000 monthly remote video hearings - not without some technical problems - are already part of the court process.

"I think we're virtually at the limit of what we think is feasible, we continue to look to see what more can be done," he says. "But I think the key now is, it's not just about capacity, it's about getting cases listed. Working with [judges], I think that we can make solid progress this year."

A court sketch from a major trial at the Old Bailey shows some of the measures that have been put in place to allow justice to continue

The Criminal Bar Association says new spaces are not enough - they need to be staffed.

Sitting days yo-yo

In 2009-10, the budget for Crown Courts in England and Wales meant judges could "sit" for more than 108,000 days. Last year, it was 86,000. That roughly equates to only 45% of available court space being used, before the pandemic hit.

Mr Buckland says reductions in "sitting days" were driven by projections of falling levels of crime. His critics say it was also a political decision to deliver cuts. He is now promising a huge increase in sitting days - above 100,000 - in effect a return to where the courts were.

"I'm working out the number of days to be agreed with the Lord Chief Justice," he says. "But I can assure everybody that that number [of sitting days] will be significantly in advance of 82,000 to many, many tens of thousands of days above that."

WATCH: Two young lawyers share their concerns about the profession

It's worth noting that before he became a minister, Mr Buckland sat as a part-time Crown Court judge.

So what does he say to victims like Jenny who are in limbo?

"That case is a dramatic example of a number of cases that concern me. I don't want to see victims and witnesses having to wait an inordinate length of time. I can understand her perspective.

"I accept what you say about the huge frustrations and the anxiety and the concern that is out there. But I'm doing everything I can to mitigate those problems."

One of the most significant changes has been the extension of the option of pre-trial video-recorded testimony and cross-examination for vulnerable victims and witnesses - in essence allowing them to give evidence long before a court hears the case.

The government has also pledged an extra £40m to support vulnerable people, external waiting for trial - including £16m for more independent sexual violence advisers - specialists who have been instrumental in supporting Jenny as she waits for justice.

Jenny meanwhile has been given permission by prosecutors to get additional help - but she can't get the specific deep counselling that could help her because the waiting list in her part of the country is staggeringly long.

"I'm resilient. I've got support. What about individuals who have got no family, no friends?" she says. "How many of those have walked away? Not because a crime didn't happen, but because the system hasn't enabled their voice to come out?

"The system is not broken because of Covid. It was well broken before that. And you might put your Nightingale courts up and running, but you need to go back to asking: what do the victims need?"

- Published19 July 2020

- Published26 January 2021

- Published19 January 2021