Prince Philip: The Duke of Edinburgh's Award 'saved me from jail'

- Published

Friends Nathan (left) and James were often in trouble with police before they signed up to do their bronze award

What does the Duke of Edinburgh's Award mean to you? For many it will conjure memories of hauling a badly-packed rucksack across rainy British countryside in the hope of adding some sparkle to their CV. Yet for some of the millions of young people who have taken on the self-improvement challenge, it has brought truly life-changing opportunities.

Without the award, James says he'd "probably be in jail". At the age of 15, James and his friend Nathan, then 16, had had more run-ins with the police than they care to remember. As bored mates growing up in Darlington, north-east England, they felt they had "nothing else to do" but to cause mischief.

Illegally riding motorbikes for a bit of fun in their early teenage years turned into a succession of petty crimes - theft, anti-social behaviour, criminal damage. James describes his behaviour as "causing mayhem". Nathan adds: "Wherever I was, I was causing trouble."

After being caught for separate offences, in 2018 the friends were both ordered to do hours of community service, or "reparations". The stint the pair enjoyed the most was being taught how to fix bikes by youth offending officer Dave Kirton, for a community project.

Dave, who is also a Duke of Edinburgh leader, arranged with those on the reparations panel to strike a deal with the boys: if they did their Duke of Edinburgh Bronze Award, external, they'd get five hours taken off their community service orders.

"It was a little bit of a reward, a carrot incentive," Dave says. "Both the lads were a bit reluctant at first, but they agreed and two or three weeks in they realised the opportunity they had - and they got stuck right into it."

It takes about six months for most participants to complete the four sections of the bronze award: volunteering, a physical challenge, developing a skill and taking part in an expedition, which usually consists of two days of walking and a night of camping. The silver and gold awards are more challenging and take longer to complete.

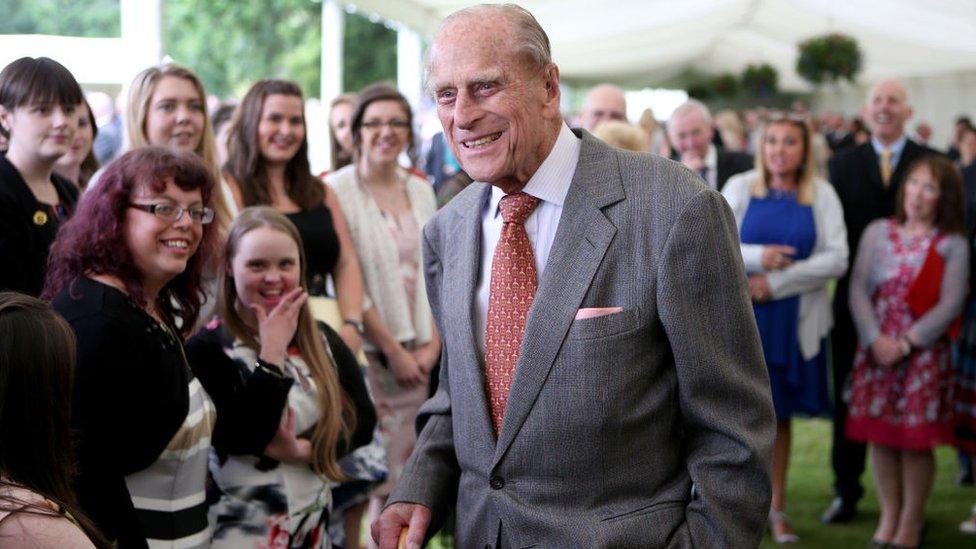

Prince Philip, pictured at a gold award presentation in 2017, believed the awards showed young people "what can be achieved through determination and persistence"

James says the commitment needed for his bronze award - the first of three achievement levels - forced a change in his behaviour: "It just stopped me being naughty." Nathan says learning expedition skills such as navigation made him realise how quick he was at picking up new things.

"There's potential that you don't know you've got until you actually try it," he says.

Nathan's realisation is exactly the kind of boost Prince Philip wanted to give young people when he first established the Duke of Edinburgh's Award for Boys in 1956. The idea, as expressed by the duke himself, was simple: "If you can get a young person to succeed in any one activity, then that feeling of success will spread over into many others."

The roots of this idea lay in the self-reliance that helped Philip through his sometimes troubled childhood, and the experience of his time at school. Gordonstoun, the school both Prince Philip and Prince Charles attended, had a tough physical regime with an emphasis on self-development - as depicted in the Netflix series The Crown.

Gordonstoun schoolboys on an obstacle course in 1956 - the same year the Duke of Edinburgh set up his award programme

In the beginning the duke's award was confined to boys, with 7,000 signing up in the first year. Girls were allowed to take part from 1958, but to begin with their programme had more emphasis on domestic skills and community service.

The programme was made the same for girls and boys in 1980 - a move towards equality that helped one girl to overcome part of her traumatic childhood.

Lauren (not her real name), was abused by her parents as a child. She says they used to dangle her from a balcony - an abusive pastime that left her terrified of heights.

During Lauren's bronze award expedition in 2018, when she was 14, she was given the opportunity to take part in a high ropes course as an extra activity. "I had a friend there that I'd met, and they were egging me on," she says. "I finally did it and I felt so relieved."

That day on the high ropes, Lauren's fear of heights disappeared. "I can do anything now," she says.

Lauren says the friends she made through the scheme have helped her gain the social skills needed to pursue a future career in social work. She says her aim is to help others who have had difficult childhoods.

Those who complete the gold award get to experience a high of a different kind - being invited to a presentation ceremony at a royal residence. Several are held each year, either at St James's Palace or in Buckingham Palace gardens, in London, at the Palace of Holyroodhouse, in Edinburgh, or at Hillsborough Castle, in County Down.

Prince Philip attended more than 500 of gold award presentations himself - and other Royal Family members stood in if he was absent. He remained a patron of the organisation until his death.

A look at the history of the programme as Prince Philip attends the 500th Gold Award presentation

Mohammed Leily says he was "thrilled" to meet "the man himself" at one of Philip's final presentation events before he retired from royal duties in 2017.

"He went around and had a chat with each group," says Mohammed, who is still in touch with the friends he made through the programme. "I remember he told us to make sure we are as active as we could possibly be, and to make sure we made use of our youth now while we have the energy."

Mohammed arrived to the UK from Syria as a refugee in 2013, aged 17, and decided to sign up for the bronze award as a way of meeting new people and improving his English. He revelled in the opportunity to volunteer for the Red Cross and help other refugees and asylum seekers settle into new homes.

He credits his gold award with helping him to get a place to study medicine at the University of Southampton - and says he still can't believe he got to meet Prince Philip. "When I left Syria I would never have imagined I'd do that, or see him."

One of the best things for Mohammed Leily was volunteering for the Red Cross, where he helped other refugees

As of early 2021, more than 3.1 million Duke of Edinburgh's Awards had been achieved by people like Mohammed, Lauren, James and Nathan. The international arm of the scheme, external means more than a million people more are currently taking part in programmes in more than 130 countries.

But if the numbers have grown dramatically, the ideas remain simple. "One of the perpetual problems about human life is that young people of every generation have to discover for themselves what life is all about," the duke said in 2010.

"These experiences teach more general lessons and serve as a practical demonstration of what can be achieved through determination and persistence."

Back in Darlington, those lessons have certainly been learned by James and Nathan. Neither has reoffended since completing their bronze award. "It makes you happy knowing you're pal's all right and doing well for himself," says Nathan. "And it makes us happy knowing that we've both changed together."

Did you take part in the Duke of Edinburgh's Award scheme? Did you meet Prince Philip? Share your experiences by emailing haveyoursay@bbc.co.uk, external.

Please include a contact number if you are willing to speak to a BBC journalist. You can also get in touch in the following ways:

WhatsApp: +44 7756 165803

Tweet: @BBC_HaveYourSay, external

Please read our terms & conditions and privacy policy

If you are reading this page and can't see the form you will need to visit the mobile version of the BBC website to submit your question or comment or you can email us at HaveYourSay@bbc.co.uk, external. Please include your name, age and location with any submission.

Related topics

- Published25 February 2016