Imprisonment for Public Protection jail terms 'a death sentence'

- Published

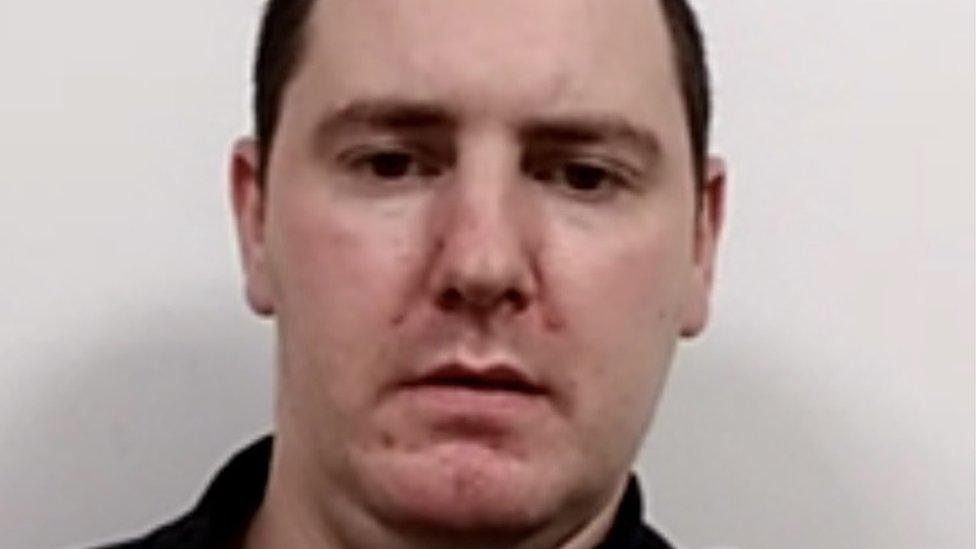

Karl Maroni, 33, has spent all his adult life in jail.

Aged 18 he committed three violent offences and was convicted.

He was told the minimum time he'd be in prison would be three and a half years.

But 16 years and 17 jails later he's still there, "left to rot", he says.

He's never had a bank account, never owned a smartphone and never used social media.

Speaking from the low-secure mental unit where he's currently detained, he says he's come close to "giving up".

"I was self-harming, getting into trouble, feeling really low and depressed, not knowing when I was going to get out," he said.

"It's like a death sentence."

Karl Maroni, 33, has spent all his adult life in jail

Maroni is serving a sentence known as an IPP - Imprisonment for Public Protection - which were abolished by the coalition government eight years ago because they were seen to be unfair.

Yet there are still 1,900 people in custody in England and Wales with no end date and no idea when they are getting out.

Former Conservative Justice Secretary Lord Kenneth Clarke, who got rid of them in 2012, has told BBC Radio 4's World At One programme it's a "tragedy" there are still so many people serving IPPs.

Another former Tory Justice Secretary, Sir David Lidington, told the programme that all remaining IPP cases should be reviewed "as soon as possible".

'I have changed'

As a teenager, Maroni took part in a robbery of a bookmakers in London.

He and an accomplice threatened the pregnant cashier with an imitation gun and demanded cash, leaving with £200.

He also refused to pay a taxi fare and showed the driver a knife, as well as carrying out a street robbery.

He says he now feels remorse for his victims.

"I was an offender," he says.

"Growing up I was a street kid. People shouldn't feel sorry for me but I have changed. I've been punished enough."

IPPs were designed for the most violent and sexual offenders.

Back in 2005, the Labour government thought they'd be used for around 900 offenders - but 6,000 people received the sentence.

Many were kept in jail for years after their tariff expired.

The prison and parole system couldn't cope with the need to give inmates access to rehabilitation programmes in order to demonstrate they were safe to be let out.

According to official probation documents, Maroni had a difficult childhood.

His mum was an alcoholic and drug user and her partner used to beat her and Maroni.

He missed three years of school and attempted to take his own life using his mother's drugs.

Since he's been in custody, his mental health has deteriorated significantly - exacerbated, he says, by having a sentence which gave him no hope.

He's self-harmed, had panic attacks and says he's been diagnosed with a personality disorder and schizophrenia.

His application for parole has been rejected several times because the parole board thought he still posed a risk to the public.

He's due to have another hearing this summer and is feeling optimistic.

Blunkett's 'regret' at IPPs

Sir David Lidington and Lord Clarke say setting a firm release date for IPP inmates would bring their treatment in line with prisoners on determinate sentences of a fixed length, but warn it could also mean "letting out people who were still considered dangerous".

Lord Blunkett, who as Labour home secretary introduced IPPs back in 2005, has expressed regret before about the way they were used for many more people than he intended or expected.

He has now told the World at One the fact there are still 1,900 people in jail on an IPPs "weighs heavily on him".

Families want all those on IPPs with a minimum tariff of under five years - like Maroni - to have their cases reviewed and given a sentence with an end date.

Only then, they say, will the legacy of these "disgraceful" sentences end.

The Ministry of Justice said in a statement: "The number of IPP prisoners has fallen by two-thirds since 2012 - and is down 13% in the last year.

"We are helping those still in custody progress towards release, but as a judge deemed them to be a high risk to the public, the independent Parole Board must decide if they are safe to leave prison."

Related topics

- Published18 September 2012

- Published14 September 2017