Rough sleepers: Long-term housing 'varies by area'

- Published

Martin used to sleep rough under a bridge, but now is in privately-rented accommodation

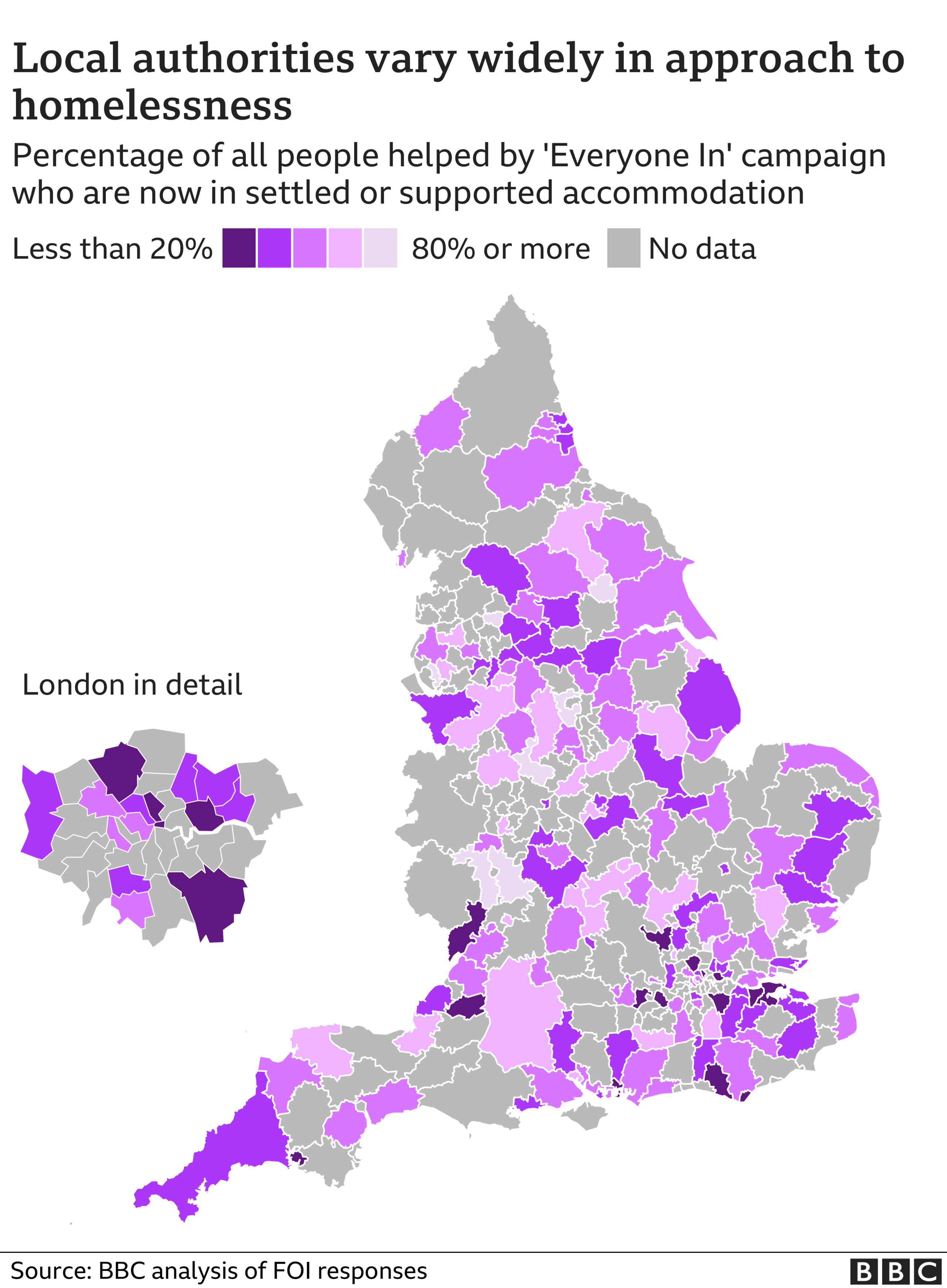

A scheme to bring all rough sleepers indoors at the start of the pandemic has seen a large disparity in the outcomes of those supported across England, new data has revealed.

In some areas over 80% of those helped are in longer-term accommodation. In others it is less than 15%.

The charity Crisis said the government must provide a clear national strategy.

Rough sleeping minister Eddie Hughes said many councils were "doing an exceptional job".

He said local authorities were best placed to allocate funding in their area, and that the UK government had provided £4.6bn of support to be spent by them.

'I felt a bit emotional'

Martin, from Shrewsbury, was one of those helped by Everyone In.

He slept rough in a concrete alcove under a bridge next to the River Severn for a year prior to the pandemic.

"I used to have a bit of carpet underneath me, and a sleeping bag and a pillow basically. And that's it," he said.

"I never felt so down in my whole life."

He said he had asked his local council for support when he first became homeless, and was told he did not qualify as he was not considered a priority need.

Martin said when he asked for support before the pandemic, he was told he was not eligible

Then on 26 March 2020, the government announced all rough sleepers in England should be brought indoors regardless of their situation. Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland had similar schemes.

Over the course of a few days, thousands of vulnerable people were placed in emergency housing.

Martin was given a hotel room - and has since been helped into privately rented accommodation.

He admits to being "a bit emotional" when he first found out he would be living in his new home.

"It's just opened doors for me. I'm now able to work again," he said.

The stability had also enabled him to become closer to his family and given him a sense of purpose again, he added.

He said he believed he would still be homeless if it was not for the pandemic.

Mixed picture

The scheme has so far helped around 37,000 people.

But figures obtained by the BBC through the Freedom of Information Act, from 174 councils that responded, have shown a disparity in the levels of long-term support provided by different local authorities.

Among the top 20 best-performing councils, on average 82.5% of those helped by the scheme have been moved into supported or settled accommodation.

This includes social housing, privately rented homes, longer-term placements in hostels and refuges, and self-contained accommodation with support worker visits.

But in the worst-performing councils, an average of just 13% have had that same outcome.

Jasmine Basran, policy manager at Crisis, said the government's decision to end its emergency funding for the scheme in May created a "lack of clarity" for councils.

She said it meant there was no longer the nationwide approach that had proved so successful at the start of the pandemic.

This led to vulnerable people's housing needs being affected by their local authority's financial situation and individual decision-making as to who remained eligible for support, she added, alongside the availability of social housing.

Crisis said the government must ensure England moved away from "a postcode lottery approach".

It has written an open letter to Prime Minister Boris Johnson, alongside charities The Trussell Trust and Joseph Rowntree Foundation, calling for a long-term strategy to tackle poverty and destitution.

Jasmine Basran from Crisis said the government must lead the way with a clear, national strategy

According to the latest government figures, of the 37,000 helped by the Everyone In scheme in England, 11,263 are currently in emergency housing.

Paul, in Oxford, has been in emergency accommodation since the start of the pandemic.

He said being housed had been a "blessing", enabling him to get better support for his medical conditions and ease his mental health problems.

"The depression began to fall away," he said.

But he now fears that support will run out.

Paul said he was worried about what would happen to him if his emergency accommodation ended

Originally from Zimbabwe, he has lived in the UK for 21 years. But as he has an immigration status, there is no duty for the council to help him long-term.

"The uncertainty of not knowing what the future holds means the anxiety is starting to creep back into life," he said.

"[If the scheme ends] it's back to square one, isn't it?"

Minister Eddie Hughes said councils had always had to make "difficult decisions", but the government had been working to help ensure those with an immigration status could access support where eligible.

He said its Rough Sleeper Accommodation Programme would be providing 3,000 new homes this year, and 6,000 in total.

The Welsh government has said it plans to ensure all those placed in emergency accommodation during the pandemic are helped into permanent housing.

Scotland has said it is "transforming temporary accommodation by transitioning to rapid rehousing [of homeless individuals] by default".