'I went from spreadsheets to proning Covid patients'

- Published

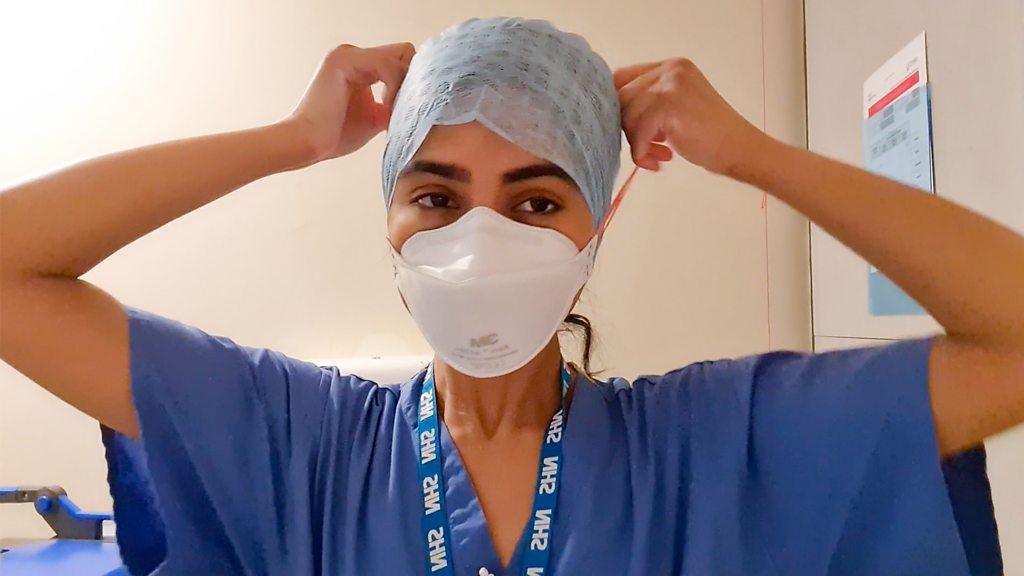

Jackie has worked in finance for the NHS for more than 40 years

As the UK emerges from the second wave of coronavirus, thousands of NHS staff - from dentists to pharmacists - are returning to their day jobs after being redeployed to help tackle the pandemic.

Jackie Armstrong normally works with numbers and spreadsheets, looking after budgets and accounts for the NHS. But as Covid cases peaked in January she signed up to work in an intensive care unit (ICU).

"Working in my normal job, it doesn't matter really if you get something wrong. You just retype the number," says Jackie, who is head of finance for the integrated medicine and emergency care divisions at Northwick Park Hospital in north-west London.

"But in that sort of environment you don't want to be getting it wrong."

When her hospital sent out a request for people who were willing to help in the ICU, Jackie's thoughts turned to her mum, who was treated there in July before she died following a stomach bleed.

"The clinical people were so fantastic with her that you just feel like you want to give something back," the 60-year-old says. "I knew that she'd be pleased I was doing something."

As the pandemic has placed huge pressures on hospitals, thousands of NHS workers have been redeployed, with many working in front-line roles.

According to a recent survey, external, about 14% of NHS staff say they have been redeployed to carry out duties outside of their normal job during the pandemic, with 8% working in ICUs.

Like many others, Jackie continued her normal role during the week but at weekends she did six-hour shifts in the ICU - working seven-days-a-week for more than two months.

She was part of the proning team - turning ventilated patients on to their front to increase oxygen flow to the lungs.

She had a couple of hours of training and was always supervised by an anaesthetist - but that didn't stop her feeling nervous as she walked into the ward in full protective equipment for her first shift.

"When some of my colleagues saw me walking around with scrubs on they did a bit of a double take and said: 'What on earth are you up to?'" she laughs.

The job was tiring - with the group of six working their way through a list of patients who needed to be proned for the entire shift.

But it was the emotional impact of the work that she found draining.

By January, there were nearly 40,000 patients in hospital with Covid-19 across the UK - almost double the figure during the first wave.

The large number of patients meant it was common for people to be there one weekend and gone the next, without any explanation whether they had died or recovered.

"I think the way I dealt with it, and I think a lot of our team was similar... we just didn't enquire because actually it's best not to know because we saw so many patients," she says.

A day in the life of an ICU nurse

Sometimes Jackie would bump into relatives of patients outside the hospital, who were only able to visit the ward if their relative was at the end of their life, to minimise the risk of infection.

"They'd stop you, thinking 'there's a doctor', and say 'my granny is in there, can you tell me how she is?' And of course we couldn't, partly because we didn't know. In a way, encountering the relative was harder than the patient."

Despite the emotional toll, Jackie says overall the experience was positive and rewarding.

"The team were fantastic," she says. "And because we were a mixture of staff with some people who were clinical and then some of us that weren't, if we ever needed to know something, there was always somebody there."

There's nothing quite like actually walking onto a unit and seeing a whole unit full of patients prone.

Redeployed staff also played a key role in the first wave last year.

Hayley Price, a 28-year-old physiotherapist, worked in the ICU at Queen Alexandra Hospital, in Portsmouth, for three months in March 2020. The experience has stuck with her.

"I can remember one week in the pandemic, I drove home, sat on my driveway in my car and just cried. We'd lost a patient," she says. "I just felt really helpless."

"I think everyone has a bit of a breaking point and that was mine because you were seeing it day in and day out."

Like Jackie, Hayley had never worked in an ICU before - her normal job involved helping patients recover from falls or operations like knee replacements.

As a physiotherapist, she had some transferrable skills - including in rehabilitation and respiratory medicine - and she was also given extra training. But working in the ICU still came as a shock.

"No matter what you hear from others, or hear on the news, or anything like that, there's nothing quite like actually walking onto a unit and seeing a whole unit full of patients prone," she says.

"Everyone's in full PPE [personal protective equipment]. So you can't meet staff. You can't even recognise them or put a friendly face to them."

LOOK-UP TOOL: How many cases in your area?

LOCKDOWN RULES: What are they and when will they end?

SOCIAL DISTANCING: How can I meet my friend safely?

Hayley helped out with everything from proning patients to getting them walking again after being sedated. She would also keep patients clean - washing their hands, brushing their hair - and keep in contact with relatives.

One of her best memories is video-calling a patient's wife with him for the first time after he came off ventilation.

"This patient's relative had sent letters to the hospital and we used to read them to him every day in the hope that he would take some of that in and know that his family were thinking of him. So to actually see the first phone call was incredibly emotional," she says.

I'll never be able to forget that patient when you first get them to walk again after a very long time of being very, very poorly.

The strain of working with such ill people in contrast to her normal job, where patients would rarely die, was also a challenge.

"To be in a situation where we couldn't talk to patients... and the thought was really just about getting them to survive this admission, was really tough," she says.

Looking back, Hayley has mixed emotions about her time in ICU.

"I'll never be able to forget that patient when you first get them to walk again after a very long time of being very, very poorly," she says.

"But on the flip side, I will always have a picture in my head of a family being allowed to come in because their relative was dying and they couldn't hold their hand without getting dressed in full PPE."

As for Jackie, she's now considering volunteering on the wards after she retires.

"Now, I wouldn't be frightened to volunteer in a more patient-facing role than I would have done otherwise," she says.

"That's quite exciting actually - that I've maybe opened doors."

"I CAN'T FEEL MY LEGS!": How a few seconds changed Grace's life

MASTERS 2021: The most memorable moments and meltdowns from previous years

Related topics

- Published6 January 2021

- Published2 November 2020

- Published23 January 2021