A nightmare on repeat - India is running out of oxygen again

- Published

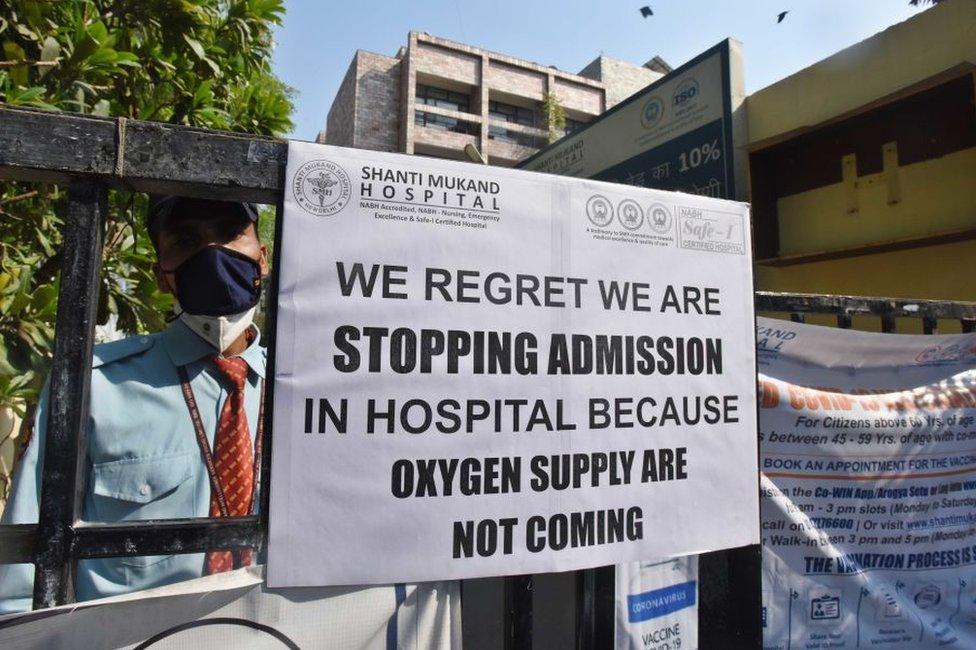

Hospitals in Delhi have been forced to display signs saying they have run out of oxygen

Twenty-five families in India's capital Delhi woke up to the news on Friday morning that someone they loved had died in the city's Sir Ganga Ram hospital, reportedly because coronavirus patients could not get enough oxygen.

The hospital's medical director said a severe shortfall had slowed the flow of oxygen to 25 of the sickest patients, who needed a high pressure, stable supply.

The tragedy came at the end of a week where several major hospitals in Delhi have repeatedly come close to running out of oxygen, which can help patients with the virus who need support with their breathing stay alive.

On Tuesday, it took a desperate public plea, external from the chief minister and an intervention from the high court for the Indian central government to organise a late night refill.

An oxygen tanker eventually arrived at Sir Ganga Ram hospital on Friday morning, shortly after a dire warning that 60 more patients were on the verge of death.

But India's rising wave of cases is pushing its healthcare system to the brink - from the country's richest cities to its remotest corners.

A battle for breath

Maharashtra and Gujarat in the west, Haryana in the north, and Madhya Pradesh in central India are all facing an oxygen shortage.

In the northern state of Uttar Pradesh, some hospitals have put "oxygen out of stock" boards outside, and in the state capital Lucknow hospitals have asked patients to move elsewhere.

Smaller hospitals and nursing homes in Delhi are doing the same. Desperate relatives in several cities are lining up outside oxygen refilling centres. One plant in the southern city of Hyderabad hired bouncers to manage the crowd.

Many stricken with coronavirus are dying while they wait. Hospitals are struggling to accommodate breathless patients, or even keep alive those who were lucky enough to find a bed. Social media feeds and WhatsApp groups are full of frantic pleas for oxygen cylinders.

For a week, India has been reliving this nightmare on repeat, waiting for the terrifying moment when there is no oxygen left at all.

Relatives beg for help as oxygen runs out

For anyone who has watched the pandemic unfold here - from doctors to officials to journalists - this feels like déjà vu. Seven months ago, the country had grappled with a similar oxygen shortage amid a rapid surge in case numbers. But this time, it's much worse.

Typically, healthcare facilities consume about 15% of oxygen supply, leaving the rest for industrial use. But amid India's second wave nearly 90% of the country's oxygen supply - 7,500 metric tonnes daily - is being diverted for medical use, according to Rajesh Bhushan, a senior health official.

That's nearly three times higher than was consumed every day at the peak of the first wave in mid-September last year.

Then, India was adding about 90,000 cases daily. Just two weeks ago, in early April, the single-day spike was around 144,000. Now, the daily caseload has more than doubled to well more than 300,000.

"The situation is so bad that we had to treat some patients in a cardiac ambulance for 12 hours until they could get an ICU bed," said Dr Siddheshwar Shinde, who runs a Covid hospital in Pune, a western district with India's second-highest active caseload and third-highest death toll from the virus.

Last week, when there were no ventilators left, Dr Shinde began moving patients to other cities - unheard of in Pune, where patients usually arrive from nearby districts seeking treatment.

Relatives of Covid patients have been queuing up in cities to refill cylinders

The state of Maharashtra, where Pune is located, is among the worst-affected parts of India, and currently accounts for more than a third of active cases. The state is producing about 1,200 metric tonnes of oxygen daily but all of it is already being used for Covid patients.

And demand is rising along with cases, and outstripping supply. It shows no signs of letting up.

"Usually hospitals like ours were able to have enough oxygen supply. But in the past fortnight, keeping people breathing has become a task. Patients as young as 22 need oxygen support," said Dr Shinde.

Doctors and epidemiologists believe the deluge of cases is delaying tests and consultation, leading to many people being admitted to hospital when their condition is severe. So the demand for high-flow oxygen - and therefore more oxygen - is higher than it was during the last wave.

"Nobody knows when this is going to end," Dr Shinde said. "I think even the government did not foresee this."

A scramble to find supply

Some governments did. The southern state of Kerala increased supply by monitoring demand closely and planning for a rise in cases. Kerala now has surplus oxygen that it is sending to other states.

But Delhi and some other states do not have their own oxygen plants and are relying on imports.

The Supreme Court has weighed in, asking Prime Minister Narendra Modi's administration for a national Covid plan that addresses the oxygen crunch.

The federal health ministry had invited bids for new oxygen plants in October last year - more than eight months after the beginning of pandemic in India. Of the 162 that were sanctioned, only 33 have been installed so far - 59 will be installed by the end of April and another 80 by the end of May, the ministry has said.

A woman with access to oxygen waits for admission at the LNJP Hospital in Delhi

The scramble to increase supply points to the lack of any emergency plan.

Liquid oxygen, pale blue and extremely cold, with a temperature of around -183C, is a cryogenic gas that can only be stored and transported in special cylinders and tankers.

About 500 factories in India extract and purify oxygen from air and send it to hospitals in liquid form. Most of it is supplied through tankers.

Major hospitals usually have their own tank where oxygen is stored and then piped directly to beds. Smaller and temporary hospitals rely on steel and aluminium cylinders.

Oxygen tankers often queue outside a plant for hours and it takes about two hours to fill one tanker. It takes several hours more for these tankers to travel to various towns within or across states.

The tankers also have to follow a specific speed limit - no more than 25mph (40km/h) - and they often don't travel in the night to avoid accidents.

The head of one of India's biggest oxygen suppliers has said part of the struggle has been getting oxygen from eastern India, where supply in industrial states such as Orissa and Jharkhand is high, to western or northern India such as Maharashtra or Delhi, where cases are rising fast.

And the demand for oxygen at individual facilities is unpredictable, making it difficult to gauge a hospital's requirement and adequately get supply where it is needed.

Transporting oxygen has become a huge logistical challenge

"Not every patient needs the same amount of oxygen for the same duration. How many patients need oxygen changes by hour in a hospital," said Dr Om Shrivastav, an infectious diseases expert at a Mumbai hospital.

"We are taking all the care we can. But I've not seen anything like this. I think nobody here has."

Too little, too late

Before the crunch of the oxygen crisis, the federal government was already facing criticism for allowing election rallies and a massive Hindu festival, and failing to expand the vaccination drive quickly enough. Critics have accused various state governments of doing too little to prepare for the devastating second wave now washing through the county.

Doctors and virologists who spoke to the BBC said the oxygen shortfall was more a symptom than a cause of the crisis - effective safety protocols and strong public messaging could have kept more people at home, and the virus at bay.

But a sharp drop in cases by January lulled the country into a false sense of safety, they said, creating the conditions for a terrible second wave.

Mr Modi's government has now started an "oxygen express", with trains carrying tankers to wherever there is demand, and the Indian Air Force is airlifting oxygen from military bases. They are also mulling plans to import 50,000 metric tonnes of of liquid oxygen.

"We have been telling authorities that we are willing to increase our capacity, but we need financial aid for that," said Rajabhau Shinde, who runs a small oxygen plant in Maharashtra.

"Nobody said anything and now suddenly, hospitals and doctors are pleading for more cylinders," he said.

"This should not have happened. As the saying goes, dig the well before you're thirsty. But we didn't do that."

Have you been affected by any of the issues raised in this story? Email haveyoursay@bbc.co.uk, external.

Please include a contact number if you are willing to speak to a BBC journalist. You can also get in touch in the following ways:

WhatsApp: +44 7756 165803

Tweet: @BBC_HaveYourSay, external

Please read our terms & conditions and privacy policy

If you are reading this page and can't see the form you will need to visit the mobile version of the BBC website to submit your question or comment or you can email us at HaveYourSay@bbc.co.uk, external. Please include your name, age and location with any submission.

Read more of our coverage on Covid-19