Infected blood: Parents and pupils reveal they were kept in dark at stricken school

- Published

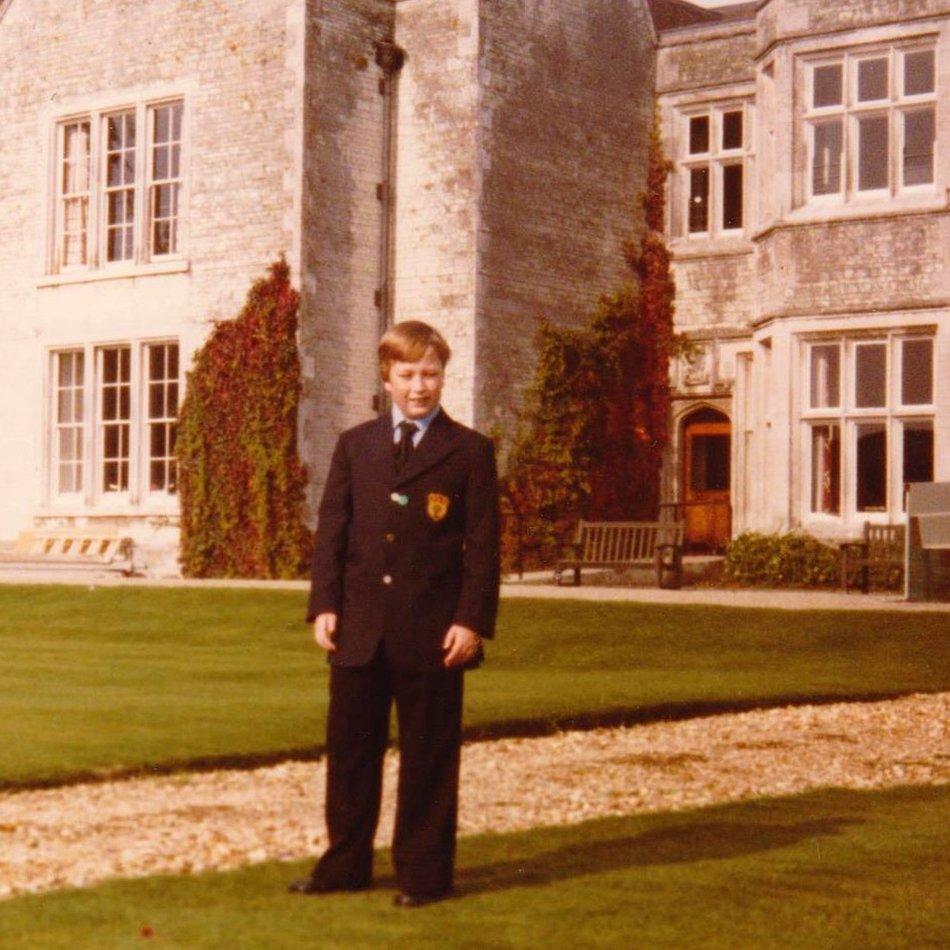

Lee Stay shortly after joining Treloar's College in 1980, aged 11

An inquiry this week heard evidence from former pupils of a boarding school where 72 of their friends died after being treated with infected blood products in the 1970s and '80s. It emerged that, as doctors were coming to terms with the fact many of the boys could have been infected with HIV and hepatitis, students and parents had been kept in the dark.

Lee Stay is not a typical campaigner. A private, quietly-spoken man, even his friends were not aware of his HIV diagnosis for many years.

This week he calmly gave detailed testimony in front of hundreds in central London.

"You haven't really done it for yourself, I think you've done it for others," said the inquiry chairman Sir Brian Langstaff, as he stepped down from the stand.

Lee was born with severe haemophilia, a rare condition in which the blood does not clot properly. It mostly affects men. His council in Hounslow, west London, wouldn't let him join his local secondary school - the risk of a severe bleed was too great. So, in 1980, aged 11, he was sent to the grounds of a stately home in Hampshire.

"It seemed very big at the time, because I'd never been to a boarding school before," he said.

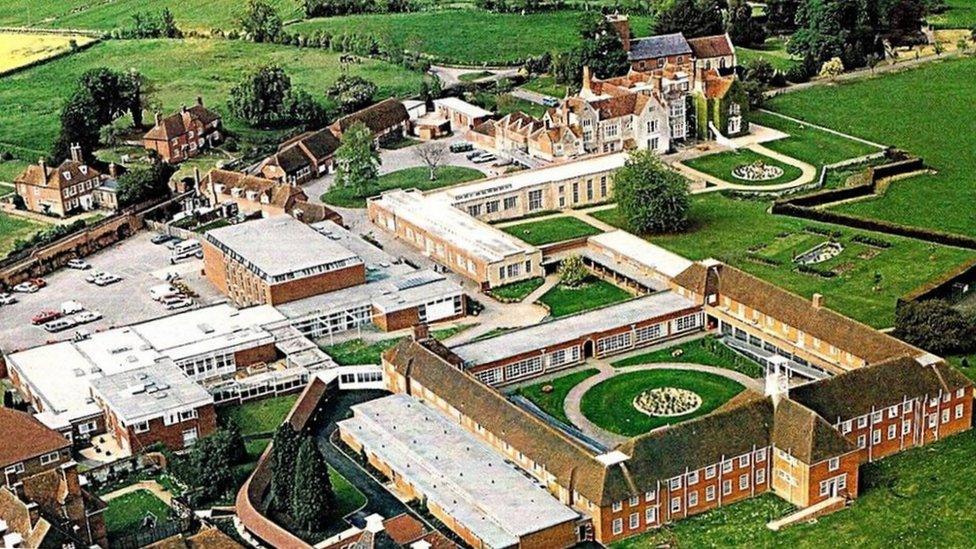

Lord Mayor Treloar College in Holybourne, Hampshire in the late 1980s

Lord Mayor Treloar College was the only site like it in the country with its own haemophilia centre, run by a small group of NHS doctors.

By the mid-1970s, treatment for Lee's condition was progressing. A new type of clotting agent called Factor VIII or IX - cut the risk of a haemorrhage. At Treloar's, Lee was taught to self-administer the clear solution, injecting it into his vein

Over the next two years he was given at least five different brands of the treatment. Other boys were given "massive doses" of a high potency product to prevent life-threatening bleeds, according to documents seen at the inquiry.

At that time, the treatment could only be made by pooling blood plasma from thousands of donors. If just one of them was infected with a virus, the whole batch could be contaminated.

But no-one was checking the supplies.

Documents released to the inquiry showed doctors knew there was a danger of infection linked to blood products. There had already been an outbreak of hepatitis B at Treloar's in 1974 and another "clutch of reports" in 1975.

Yet, Lee, now aged 52, said that he had not been told about the risks nor had his parents.

"[My parents] were never given a record of what bleeds I had, what treatments I had, what blood tests I had. To my knowledge, they had nothing," he said.

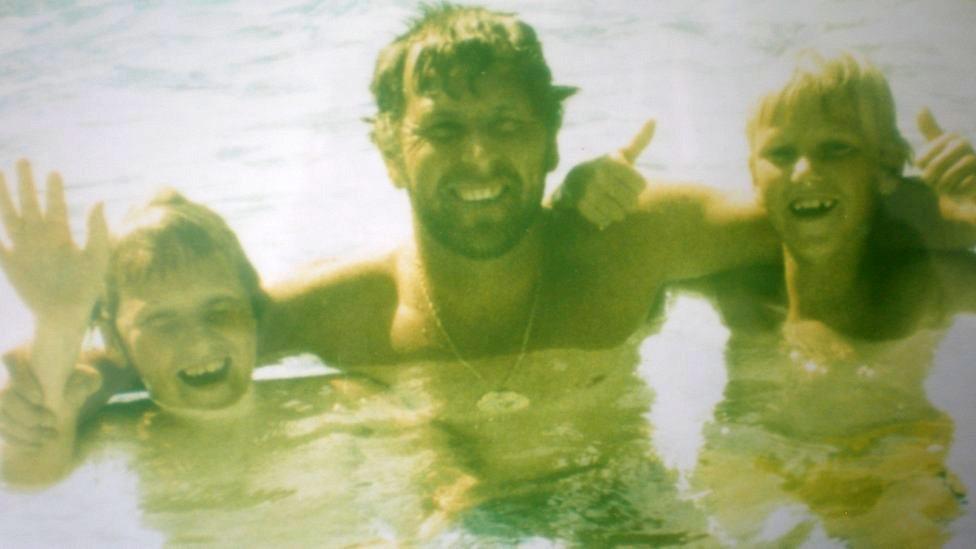

Lee, here with his parents in 1984, was already being tested for Aids at this point although none of them knew that

By 1981 reports of another virus had begun emerging from New York's gay community. In 1982 the US published its first bulletin, external linking haemophilia treatment with what would become known as Aids.

Yet it took some 40 years, as part of the current inquiry, for Lee and other survivors from Treloar's, to find out that doctors started monitoring them for the disease as early as 1983.

A letter sent by M Wassef, a doctor at Treloar's haemophilia centre, to Lee's consultant in June 1983 - and revealed at the inquiry - said he was already conducting "Aids-related investigations" on Lee. Just as Lee and his parents had not been told about treatments, so they were kept in the dark about these tests.

All the while, the use of Factor VIII at the school continued as it did in hospitals and haemophilia centres across the country.

The father of another two Treloar's pupils looked shocked when he was shown similar documents at the inquiry.

"Especially not that early, 1983. Christ," said John Peach, the father of Leigh and Jason.

John Peach and his sons Leigh and Jason

Jason's medical records from Treloar's in July 1985 refer to "stigmata of Aids" such as "some thrush and difficulty swallowing". But their father said he was not told about the possibility his son was ill and did not learn about his eventual HIV diagnosis until December 1985, after a doctor in Oxford carried out blood tests.

Jason and Leigh died of Aids six months apart in 1993 and 1994.

All of the senior NHS staff who worked at the haemophilia centre on the Treloar's site have since died. But former headmaster Alec Macpherson told the inquiry he found it "hard to believe" doctors would not have acted straight away if they had known about the danger of contamination.

"[I'd be] very surprised if that is true and I would be pretty horrified and disgusted as well as that's not how I would have wanted it dealt with," he said.

Yet it's clear a lot of the burden of understanding was put on very young shoulders.

"They said they didn't know how long I would have left," said Lee Stay, remembering when he was eventually told he was HIV+, aged 17. "It could be anything from a couple of years to 10 years, but the outlook was bleak. I thought, well, I just need to get on with my life the best I can with what time I've got."

Like others who gave evidence, he cannot remember his parents being informed by the school and thinks he had to break the news himself. He said he was never offered counselling and support.

Alec Macpherson said it would have been the responsibility of the NHS medical staff, not teachers, to tell the boys and their parents, but he would have "absolutely expected" families to have been informed.

"All the boys had someone they could talk to who was willing to listen to them," he said. "[T]hey had… a rage inside them, a frustration, that suddenly they had been made ill and they were going to die in the not-too-distant future."

In 1988, Lee left Treloar's College, eventually going on to work for the ferry company P&O and getting married. He was later diagnosed with hepatitis C. He has had three different types of cancer, a liver transplant and, more recently, severe stomach pains, all linked to the Factor VIII he was given as a child.

"As a result of being infected, I have lost my job, my home, my wife, my ability to have children, the possibility of a decent pension, had numerous serious health issues and who knows what other health condition could yet materialise," he said in his final statement to the inquiry.

In a statement, Treloar's School and College, which still cares for disabled children said: "Although the NHS clinic closed decades ago, we continue to stand with all those affected. We trust that the inquiry will find the answers needed for our former students and indeed all the thousands of people who were infected with hepatitis and HIV across the UK as a result of this tragedy."

Related topics

- Published1 May 2019