Channel crossings: France and UK clash over Border Force tactic plans

- Published

UK Border Force officials working with migrants brought into Dover harbour on Thursday

France has hit out at the UK over plans to turn back some boats carrying migrants across the Channel to England.

The government wants the Border Force to turn away boats - but only in limited circumstances under a pre-authorised policy signed off by Home Secretary Priti Patel.

France said this would break international maritime law, and also accused the UK of financial blackmail.

Boris Johnson's spokesman has said any new plans will be safe and legal.

The UK's Border Force has been training for months to use the highly controversial tactic of turning boats back in certain circumstances.

Government sources told the BBC that the final training may take place within days, subject to the weather, meaning the tactic could be in place and ready to be used whenever the UK thinks it is practical, safe and legal to do so.

But France - as well as campaigners and critics - have questioned the legality of the plan. They believe it breaks international maritime law, which says people at risk of losing their lives at sea must be rescued.

The government's lawyers say turning boats back would be legal in limited and specific circumstances - although they have not confirmed what these will be.

A man being brought ashore in Dover on Thursday

In a strongly worded tweet,, external French interior minister Gérald Darmanin said France would not accept any practice that breaks maritime law.

"UK's commitment must be kept," he said. "I clearly said it to my counterpart Priti Patel. The friendship between our two countries deserves better than posturing which undermines the cooperation between our ministries".

He also accused the UK of financial blackmail - referring to a deal the UK and France struck over money earlier this year, when the British government promised to pay £54.2m for extra action on the French side of the Channel such as doubling the number of coast patrols.

Since then, Ms Patel has warned that Britain could withhold the money, unless more boats are intercepted.

The PM's spokesman rejected those accusations, saying the government has "provided our French counterparts significant sums of money previously, and we've agreed another bilateral agreement backed by millions of pounds".

And he said: "Any approach Border Force use is safe and legal. Our operational activities comply with domestic and international law."

He added that "we continue to evaluate and test a range of safe and legal options" and any approach "is tested through multiple sea trials".

The UK has a legal right to intercept people at sea where necessary to prevent crime or to protect borders.

But whatever the legal advice the UK government has received on migrant boats, it's questionable whether such an operation could continue once there is a clear sign of danger.

Border Force commanders, like everyone else at sea, are under an international legal obligation to protect life where possible.

So their window of opportunity to run a push-back operation could be very tight.

But more importantly… is this really ever going to happen?

The intervention from the French interior minister may have just sunk the operation before a single Border Force ship has set sail.

There are no international waters in the Dover Strait - so any operation would need French co-operation.

And Gérald Darmanin's statement makes clear France's opposition to any confrontation of dinghies in one of the world's most dangerous shipping lanes.

Charities and opposition politicians have also criticised the plan.

The British Red Cross said it was concerned that sending people back to sea could "make already treacherous journeys even more perilous".

"Crossing the Channel in a small boat is only ever a desperate last resort, and an extremely dangerous one. When people's lives are in danger they need help, compassion and humanity, not to have their ordeal extended."

Amnesty International UK said people "only make dangerous journeys and rely on smugglers because there are no safe alternatives made available to them".

And the boss of charity Refugee Action said the policy was "about bullying refugees to score political points rather than breaking up smuggling gangs.

"We all want the boats to stop but this plan massively increases the chances of families drowning at sea."

Labour also said the tactic risks lives, adding: "That the home secretary is even considering these dangerous proposals shows how badly she has lost control of this situation."

Boats used by migrants to cross the Channel are stored at a warehouse in Dover

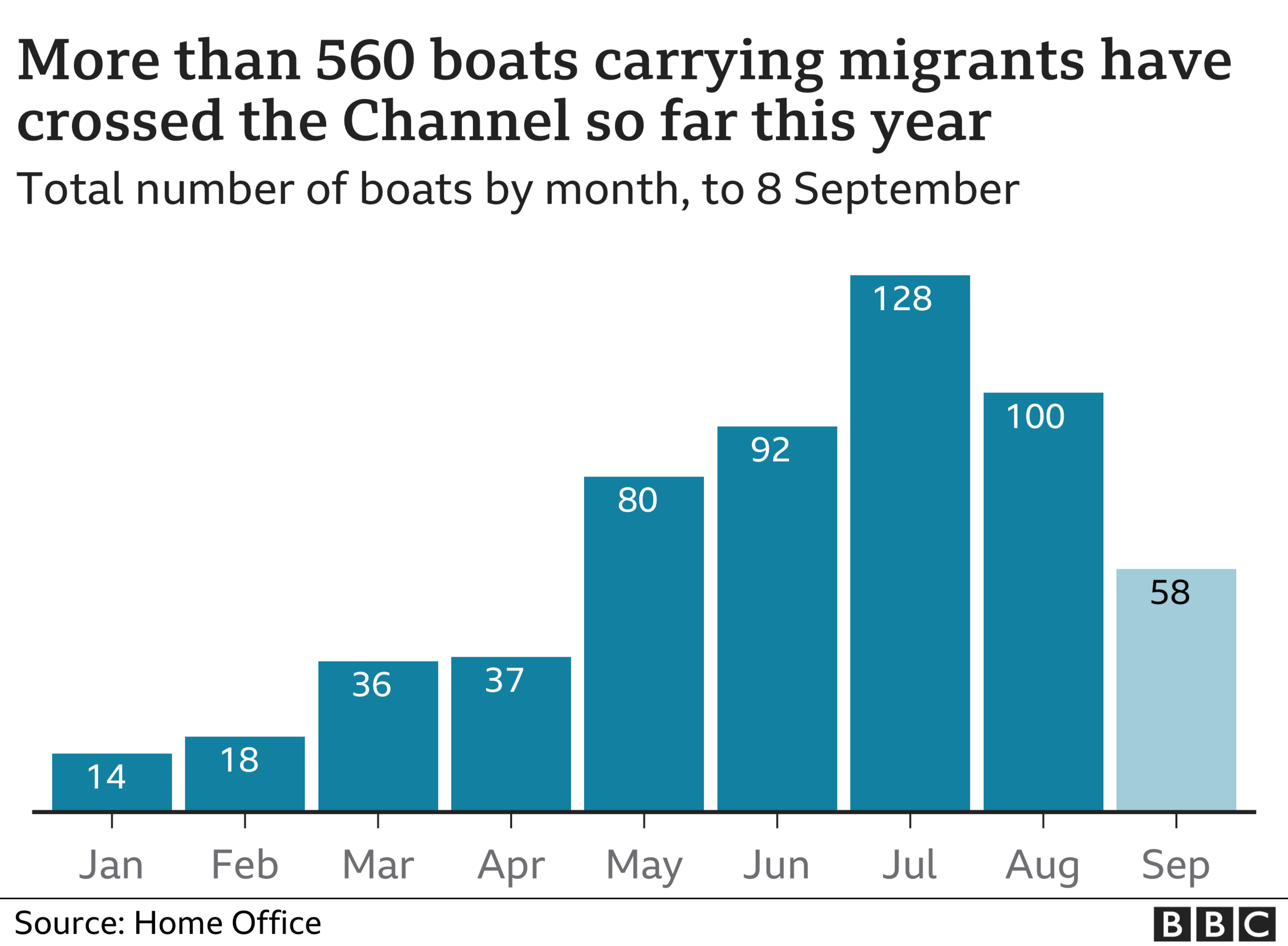

Rising numbers of migrants have been crossing the English Channel in recent months - since Sunday more than 1,700 people have crossed by boat.

And in total this year, more than 14,000 migrants have made the journey across.

The Channel is one of the most dangerous and busiest shipping lanes in the world. Many migrants come from some of the poorest and most chaotic parts of the world, and many ask to claim asylum once they are picked up by the UK authorities.

The government has previously spoken of cracking down on the organised crime gangs who smuggle people across the Channel, often for profit.

On Thursday, No 10 said the public expects the government to act.

"We know this is a long-standing problem that the public expect us to address. It simply cannot be right that dangerous... that criminal gangs are able to exploit our most vulnerable and put their lives at risk.

"It needs to be addressed, it's what the public want, and it's what we're doing."

What happens to migrants in the English Channel?

If migrants are found in UK national waters, it is likely they will be brought to a British port

If they are in international waters, the UK will work with French authorities to decide where to take them

Each country has search-and-rescue zones

An EU law called Dublin III allows asylum seekers to be transferred back to the first member state they were proven to have entered but the UK is no longer part of this arrangement and has not agreed a new scheme to replace it

"I HAD HOPE THAT ONE DAY I WOULD BREAK THROUGH": The prize-winning novelist Bernardine Evaristo

GOING 'FILTER FREE': Will Hayley decide to drop the filters and embrace her 'flaws'?

- Published8 September 2021

- Published7 September 2021

- Published6 September 2021

- Published14 August 2021

- Published21 July 2021