James Bond and MI6: Is there fact in fiction?

- Published

No Time To Die is Daniel Craig's fifth and final James Bond film

Finally. After pandemic-induced delays and a sudden change of director, the latest long-awaited Bond movie is hitting the screens. No Time to Die is the 25th Bond movie and Daniel Craig's final outing as James Bond.

So does the Bond fantasy bear any relation at all to life in the real MI6, Britain's external spy agency, more properly known as the Secret Intelligence Service (SIS)? And perhaps more importantly, how relevant can a spy agency be in this digital age?

"I think the biggest way it differs," says Sam (not her real name), "is that we're much more collaborative than the people in Bond. Very rarely, if ever, would you ever go out by yourself, unsupported. It's all about teams... you've always got a security team around you."

Sam is a career MI6 case officer with a background in counter terrorism, one of several serving intelligence officers I requested to meet and interview ahead of the latest Bond release.

Alright, so if they are not Bond, what exactly do real-life MI6 officers do, whether based in their Thameside headquarters or out "in the field" overseas?

"There's an enormous variety of roles that you can do," says Tara, also not her real name. "There's agent-running and recruiting, we need technical experts, we have comms teams, there's a sharp edge on the front line. It's never one person on their own. There's very little resemblance of the reality of working for SIS. So I think if someone came wanting to do that they would quite quickly realise in the application process that this was not for them."

Armed? Do MI6 officers ever carry firearms? I get the official response: "We can neither confirm nor deny that."

But another MI6 officer told me: "The idea of having some guy crash-banging his way around the world shooting people up is absolute anathema to us. Someone like that simply wouldn't get in the door."

But step back a minute and consider some of the more dangerous parts of the world where Britain's overseas intelligence-gatherers are likely to operate, and it is hard to imagine that if not actually armed themselves, then someone very close to them will be tooled up and watching over them.

Strictly speaking, MI6 officers are not agents. They are intelligence officers who, at the sharp end, try to persuade the actual agents - who could be well-placed individuals, say, inside an al-Qaeda attack-planning cell or a hostile state's nuclear research facility - to steal vital secrets on behalf of Her Majesty's Government.

It is the agents who take the biggest risks every day, and it is clear that MI6 goes to great lengths to protect their identities and their families.

So how close does an agent-runner get to their agent, I ask. Can they ever be friends?

"There's a reliance on each other," says Tom, another serving officer. "You're responsible for someone's life so you say things to each other that they might not want to hear, you might have difficult conversations, but it's all about their safety."

"People do put their lives at risk in order to work with us," Tara adds. "Some of them are not very risky. But there is a category of people that it's our privilege to work with, who, if they were found out to be working with us, would be in grave danger. They could lose their lives, and we take that very seriously from the very first moment of interacting with that person."

A general view of the MI6 headquarters in London

A lot has happened in the real world of espionage in the six years since the last Bond film, Spectre, in 2015. The Islamic State group's self-declared caliphate has come and gone, the deal to contain Iran's nuclear ambitions has all but collapsed and China is making noises about "taking back" Taiwan. Plenty here to keep MI6 busy.

But in an age where almost every action we take leaves a digital footprint, is there still a place for old-school human intelligence, the time-honoured art of persuading some people to help steal other people's secrets?

"If you look at the sort of end-to-end lifecycle of data to its actually being analysed," says Emma, again not her real name, a senior in-house technical officer, "there are people involved at every step of that process. And those are the relationships that we'll be building. Of course we're working on harnessing all of those technologies to support our intelligence officers in the field."

So is there an actual workshop full of gadgets deep within the bowels of MI6 headquarters in London's Vauxhall Cross? Yes, apparently.

"It's quite different to what we see on the films," Emma says. "I have a much larger team of engineers working for me delivering new capability. And unlike in the films we're not all wearing white coats and we don't all look like geeks. [But] in terms of gadgets, we work very closely with intelligence officers to find out what they want."

Nearly 60 years have passed since the first Bond film, Dr. No, in 1962, and a further 10 years beyond that since the author Ian Fleming first created this fictional character after working for naval intelligence.

Since then, the shape of espionage has changed beyond recognition.

There are officers at the upper echelons of MI6 today who began their careers in a time before either mobile phones or the internet, let alone social media. Records were largely held in physical safes and steel filing cabinets. Biometric data was not yet in use and officially, MI6 did not even exist until 1994. Back then it was still relatively easy to get an undercover intelligence officer across a border and into a hostile location using an assumed identity and sometimes, literally, a false beard and glasses.

It is harder these days - although not impossible. Take the Russian GRU team that travelled unimpeded to Salisbury in 2018 in order to, according to the Met Police, assassinate the former KGB officer Sergei Skripal.

Today the data revolution, complete with iris recognition, biometric data, AI, cyber, encryption and quantum computing, has placed a premium on technology in espionage.

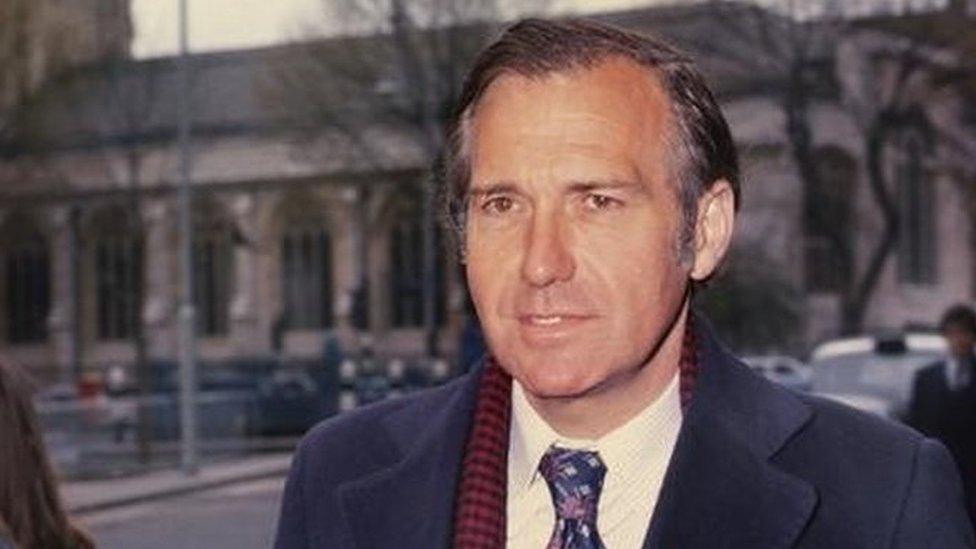

But human intelligence will always be indispensable, says Sir Alex Younger, who ran MI6 for six years until last year. His fictional on-screen counterpart, M, as played by Ralph Fiennes in No Time to Die, warns prophetically that "the world is arming faster than we can respond".

It is something that clearly keeps the real-life women and men of MI6 turning up for work.

Related topics

- Published9 September 2021

- Published12 August 2021

- Published27 July 2021