The challenge of being gay and an MI6 spy

- Published

Earlier this month the chief of MI6 issued a public apology for the historic treatment of LGBT employees. Until 1991, there was a ban on openly gay staff serving inside the intelligence agencies, which Richard Moore called "wrong, unjust and discriminatory". One former member of MI6, who is gay and served before the ban was lifted, tells the BBC that the apology was welcome but overdue.

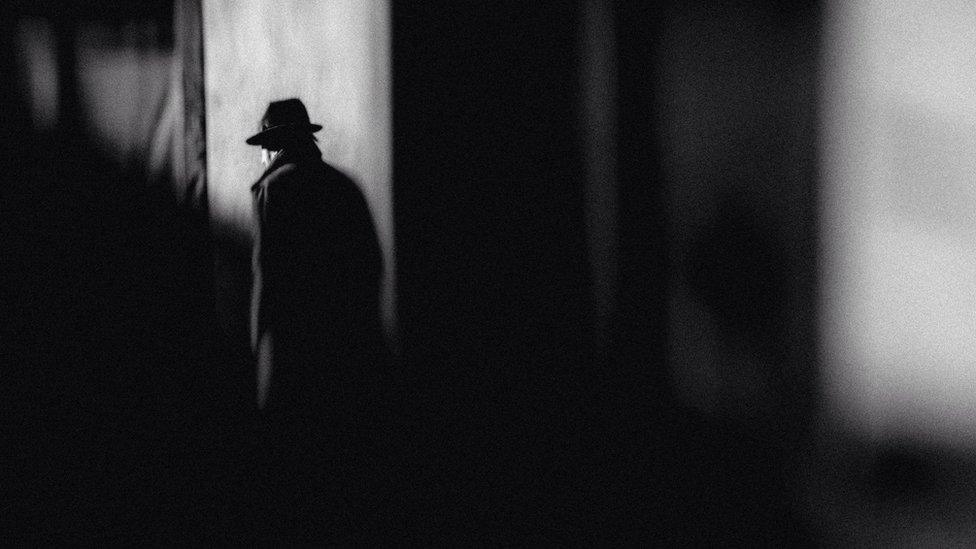

Being a spy can mean leading a double life - maintaining your cover by telling friends you work at the Foreign Office when in fact you head to MI6 in the morning. Or when you are abroad perhaps taking on an entirely new identity to meet an agent.

But being a gay spy in the Cold War meant leading a triple life. There was an additional layer of secrets, a clandestine life hidden even from your colleagues in the world of espionage.

That was because even though homosexuality had been legalised in Britain in the 1960s, it was still banned within the secret service because of a presumption that homosexuality made someone "unfit" for access to classified information.

This led to a constant fear of being outed not just as a spy but as gay. And that would, as it did in some cases, lead to dismissal.

"It could happen at any moment," recalls a former spy. "Same sex relationships were impossible in the current understanding of the term forcing any attempt at relationships deeply into the shadows," he says.

He experienced this first hand and watched the impact on others.

"They lived their already stressful professional lives against the constant fear of discovery either by their employers or their Cold War enemies."

Some were sacked but others covered up, which could still cause damage.

"Some married in an attempt to conceal their homosexuality only for some of these sham marriages to collapse in divorce. Whole families were impacted not just individual officers."

Former intelligence officers say problems at MI6 did not end when the ban was lifted in 1991

There was a concern among the intelligence services that gay operatives were more susceptible to blackmail, and this concern was used to justify the ban.

In the early 1960s, a civil servant John Vassall had been photographed in Moscow and then blackmailed by the KGB to provide secrets.

And yet during the Cold War one of Richard Moore's predecessors as chief of MI6 was himself gay.

Maurice Oldfield, chief in the late 1970s and then security and intelligence coordinator to the prime minister, had his security clearance withdrawn in the final months before he died in 1981 as his secret first emerged - although the truth only became public in 1987 in a statement to Parliament.

A number of MI6 officers serving at the time say they were shocked and had no idea.

One officer says the episode, along with the occasional report of someone being dismissed, were a reminder of how "precarious" his existence was.

In 1991, the bar was lifted. But things did not change overnight.

The restrictions had also affected Foreign Office colleagues. Richard Wood, the current Ambassador to Norway, recently published a blog about his experience., external

"There was no amnesty for those who joined before the ban was lifted, so many of us lived in fear even afterwards.

"I was outed to security department by colleagues while on my first posting, then put on the next flight home and told to expect dismissal. I was allowed to stay, but the price was heavy: a list of family and friends I was forced to come out to; a pink tag attached to my personnel file, and years of resentment and fear."

Inside MI6, change was slow, says one former officer.

"There were three communities - those who embraced the change, those who opposed it openly or in the background by their actions, and those in the middle who drifted in the wind according to events," says one individual.

"Throughout the 90s, there were direct discriminatory impacts on families and partners, allowances, pensions, promotion, career management and postings.

"Homophobia was never acknowledged but it could be concealed, even to the point of records being modified to hide it."

There were heroes at the time, including a head of vetting within MI6 who "worked tirelessly to achieve equality", according to one person, but he believes many in senior leadership were unable to conceal their discrimination.

Over time, he says, the "dinosaurs" became extinct and the sense of inclusion slowly grew.

The recently appointed chief, Richard Moore, said the security bar had been "wrong, unjust and discriminatory".

In a video posted on Twitter 30 years after the ban was lifted, he said it had deprived MI6 of talented staff who wanted to serve their country.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

Former officers are pleased by the statement but say "it's not obvious" why it has taken MI6 so long to apologise leaving it behind sister agencies. Robert Hannigan, the then director of GCHQ, did so in 2016 while the then-MI5 director general did so in a 2020 interview with the BBC.

"They are pretty much last in the queue," one says, questioning why previous leaders did not take the step.

Current members of staff told Pink News they felt the push towards equality felt genuine, external rather than a box-ticking exercise.

A former officer argues current staff should be proud of where the organisation has got to, but also aware that it has been a long and difficult journey.

- Published19 February 2021

- Published21 January 2019

- Published20 January 2016

- Published8 November 2014