‘His voice became my constant companion’ – how Dan Johnson kept his dad’s memory alive

- Published

When BBC correspondent Dan Johnson posted on Twitter shortly before Christmas that he had finished editing a project capturing the voice of his late father Graeme, he was surprised by the reaction. It made him consider the importance of preserving the memories of loved ones.

Through the dark days of December, my dad was a constant companion. He spoke to me almost every day while I limited my social life to protect my Christmas plans. I couldn't speak to him, though. He'd died four years earlier.

I'd finally got round to editing his own personal version of Desert Island Discs - the long-running BBC radio programme where guests share the soundtrack of their lives - recorded in his last few months. I listened over and over to set the sound levels, carefully piecing together his audio jigsaw - the music that meant the most to him, and the comedians who made him laugh.

He had lung cancer, despite never smoking, and while we knew his life would be shortened, his outlook was positive - he was responding to treatment and focused entirely on living. We never discussed death. His suggestion, that we sit down and cover everything from Dusty Springfield to The Moody Blues, Morecambe and Wise to Eddie Izzard, was the only hint of something to leave behind, apart from a bench overlooking his favourite view across Green Moor cricket ground high on a hill in South Yorkshire.

It's the sort of talking we didn't do much of. He was a fairly typical Yorkshireman when it came to emotions. Besides that, I wouldn't have felt able to raise the idea for fear of negatively affecting his optimistic outlook, maybe even his chances. But thankfully, he was up for it and signalled a willingness to step outside our usual comfort zone. Even if his intention was to speak only about songs and sketches, I saw a chance to nudge him into reflecting a little on life and the things that made him tick.

We started recording on a wet and windy night in September 2017, hunkered down in the old station master's house at Ribblehead, by the impressive viaduct in the Yorkshire Dales. We were away for a few days in one of his favourite spots, where he'd stayed decades before as a boy scout on his first night away from family in Hull. Now he'd been drawn back.

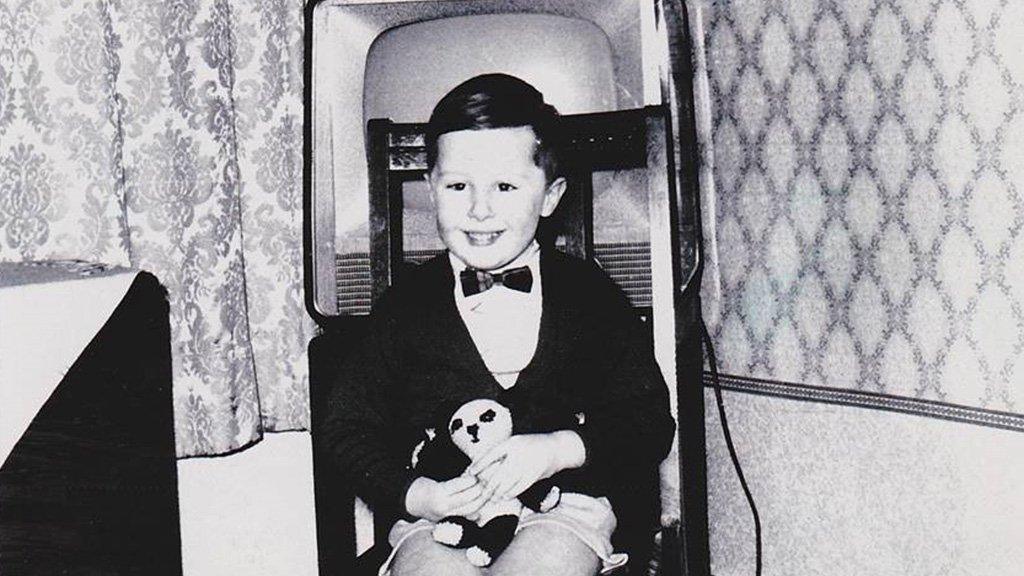

Graeme said he was introduced to the power of music through a neighbour's radiogram in Hull

He'd already given me a scrawled list of clips to play next to the warming fire as trains passed by the window. I waved a microphone towards him and he explained he thought it would be a nice thing to hand on, something he wished he had from his parents and grandparents.

As we embarked on the list, he described a fascination with sound, its power and projection, that began as a young boy at the house of a neighbour who had a big radiogram. He captured typical family life at the end of the 1960s, gathered around watching the Morecambe and Wise Christmas special and having to take his turn on the new "Hi-Fi system" to play his budding LP collection that started with the Beatles' Abbey Road. The older girls next door had asked if he wanted to see the Beatles with them at Hull's ABC cinema. His parents said 12-year-old Graeme was too young.

I never knew he'd flunked his A-Levels and been forced to take a gap year to weigh up his options. He spent that summer in France, working on a campsite, where the local kids played Pink Floyd's Dark Side of the Moon on the bar's jukebox.

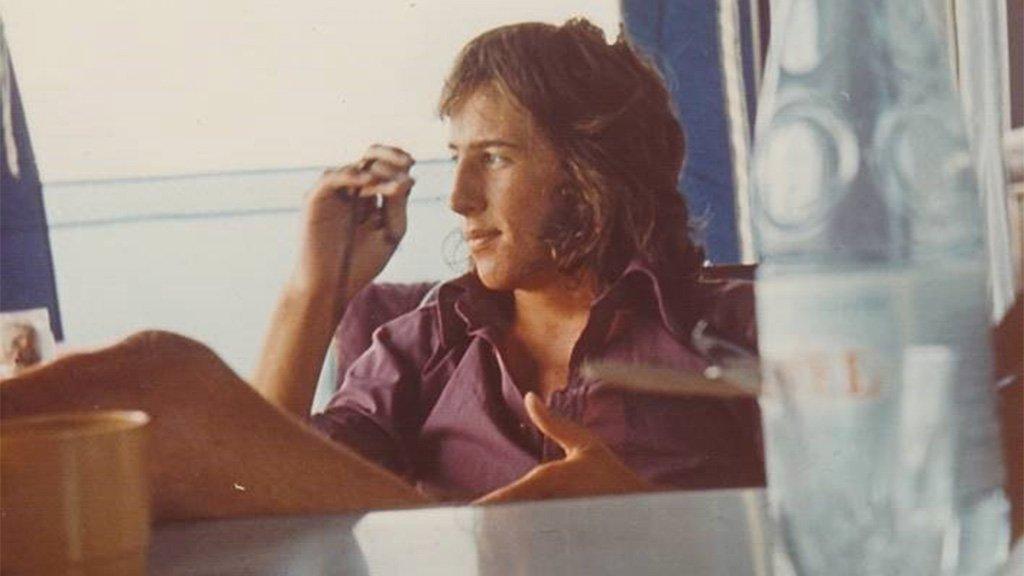

Graeme had hidden a teenage love of Motown because he said it wasn't cool at the time

He went on to build a career in town planning, which took him to Liverpool, Nottingham and Barnsley, where he worked on redeveloping a landscape scarred by coal mines and coke works. He'd drag me and my sister along the redundant railway lines converted to cycle paths or march us up replanted slag heaps to see the new roads and modern warehouses which were replacing the old industries.

In the old station master's house, we talked about Van Morrison being a grumpy old man but a great performer. He remembered Bruce Springsteen's epic live gigs full of energy. He described a secret teenage love of Motown, hidden because it wasn't deemed cool at the time.

As he relaxed a bit, he confessed some thoughts of "what if", but was content things had worked out well. He'd made plans in life but had always been flexible, prepared to take opportunities and confident things would be fine.

After three recording sessions, we were about two thirds of the way down his playlist when time ran out. I started editing soon after his lungs suddenly deteriorated at the end of 2017. But I found it tough. It was upsetting and I faced a difficult decision. Without a proper ending, I wasn't sure how to wrap up his unfinished symphony. I wonder if I was also reluctant to complete what had become the last task of his life.

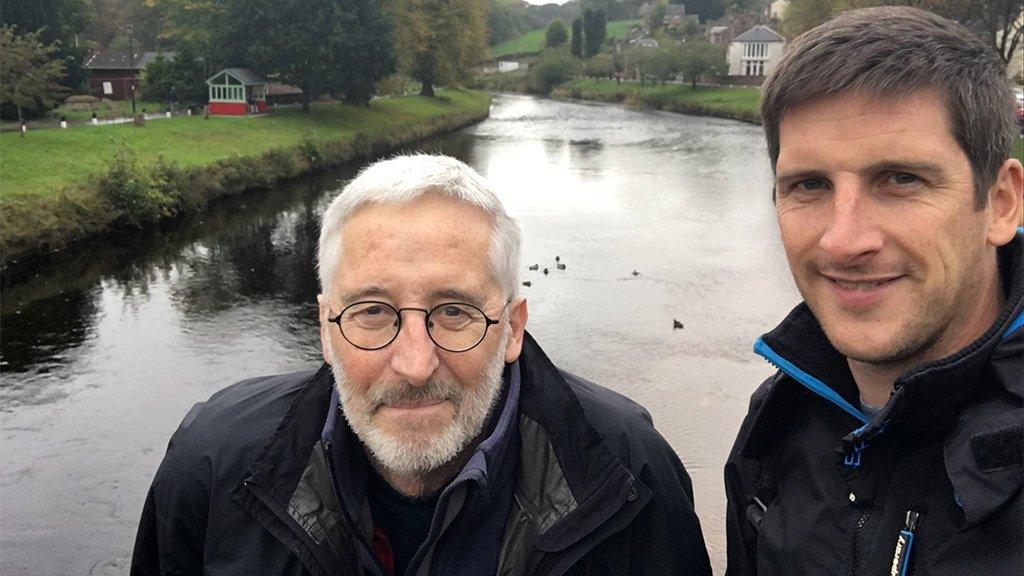

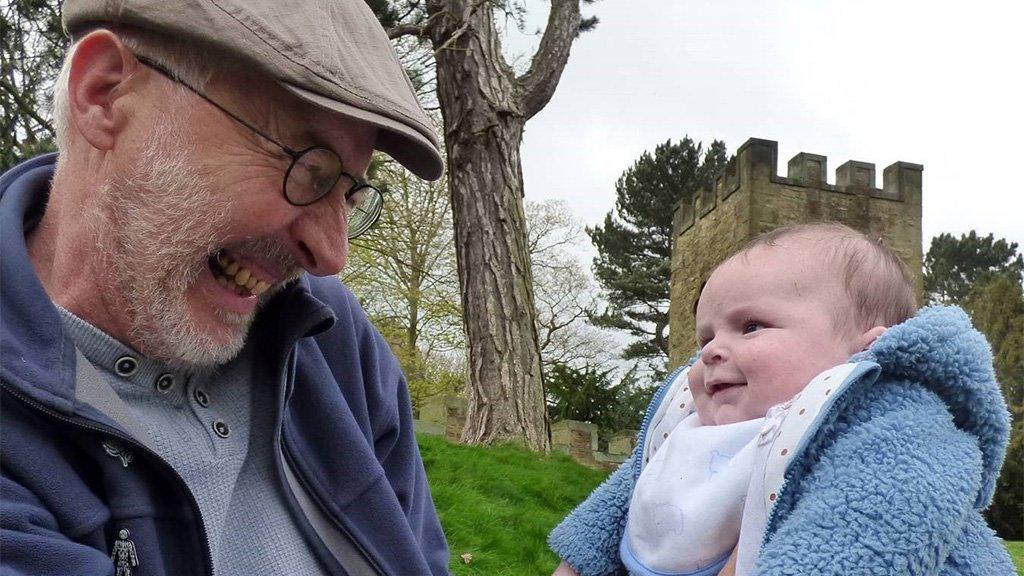

Dan and Graeme on the weekend they made the recording in the Yorkshire Dales

True to form, he'd left a list of scribbled suggestions, so eventually I took that, explained his spoken contribution would end there, then let his other choices play through.

There was other stuff that went unsaid. He chose Dear John, sung by Eddi Reader but written by Kirsty MacColl about the end of her marriage. My dad referred to his own divorce, but he didn't say much and I didn't press him. "It had a resonance, it rang a bell," he said. "It made me think, yes, she's captured that very well."

These were hints of deeper meaning behind his choices, even the entire project. He was more emotionally engaged than he let on. He'd learned to love music listening to albums in their entirety, through upbeat hits and darker melodies, changing moods and different tones. He took the rough with the smooth and focused on the overarching narrative, aware that development comes in stages and hopeful that it would be alright in the end - whatever happens along the way.

Some of my family were wary of listening to the finished recording. They'd had four years of radio silence and had to brace themselves to hear his voice again. My sister said it wasn't the gut punch that she'd feared it might be. She found it warm and comforting, not distant or upsetting. The familiarity reassured her that she hadn't forgotten him. Van Morrison brought tears because Brown Eyed Girl had been set as his ringtone.

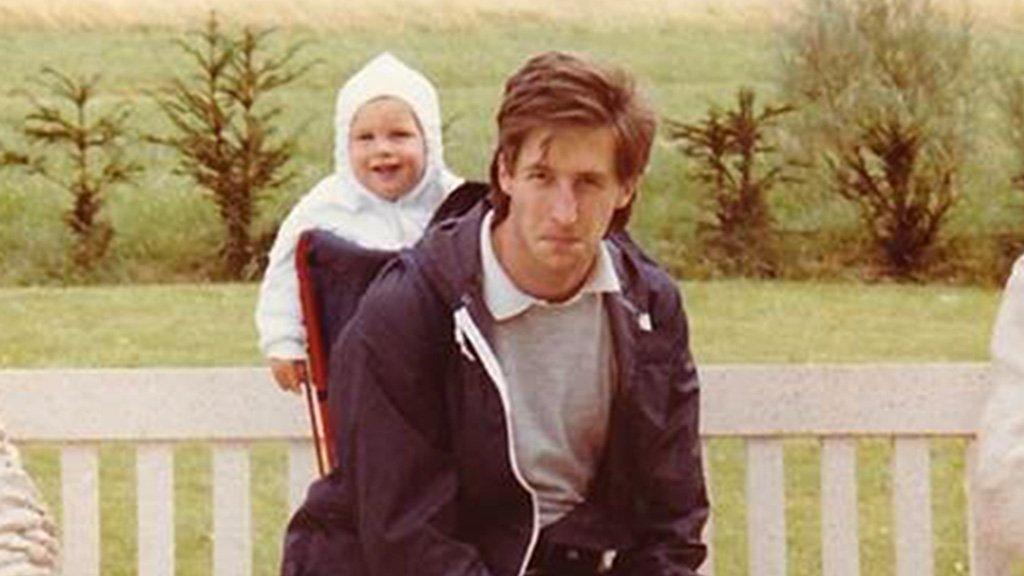

Graeme with his grandson Ted

I appreciate we're really fortunate to have this. I know so many others do not, and I'm sorry. I hope photos, videos and stories can help keep memories fresh and flowing. Death has snatched suddenly from so many families, without even the chance to say goodbye. But if you have the opportunity, make the most of it - get something recorded. It doesn't matter what you talk about. The reflections and insights are powerful but really, it's much simpler than that.

I'll never hear my dad as an old man, the tales he would have told his grandsons, the new interests he'd have immersed himself in. But he left me his snorting, sniggering laughter, the traces of his Hull accent still stretching out his words, and his friendly voice preserved in all its rich, gentle warmth.

"I may be old, but at least I got to see all the best bands," he said, quoting one of his own statement t-shirts. It's arguable. He'd only just turned 63 and, as he said himself, he never did see the Beatles.