When did young Elizabeth realise that one day she would become Queen?

- Published

The young princess Elizabeth, far right, with her little sister Margaret, and her parents when they were Duke and Duchess of York

It is often said that Queen Elizabeth II lived out the first decade of her life with little expectation of her royal destiny. She was a carefree child, apparently, who spent her time playing with her horses and dogs, blessedly free from the shadow of what lay ahead.

This Sunday marks the 70th anniversary of her becoming Queen. The young Princess Elizabeth has been compared to the modern-day Princess Beatrice - daughter of the second-ranking Duke of York ('Bertie' in 1926, Prince Andrew today), and hence remote from any serious prospect of succeeding to the British Crown, let alone reigning over the 500 million or so inhabitants of what was then known as the British Commonwealth and Empire.

December 1936 thus became the dramatic turning point in this scenario when her Uncle David, King Edward VIII, stunned the world and his family by abdicating the throne to marry Wallis Simpson, his divorcée American mistress - throwing the 10-year-old Elizabeth into the direct line of succession. Her father Prince Albert took the title of King George VI, and his elder daughter now became his immediate heir - the very first in line.

Baby Princess Elizabeth with her grandmother Queen Mary in 1926

But was the young princess really so unprepared?

"Papa is to be King," Elizabeth informed her six-year-old sister Margaret Rose that December day, explaining the sudden cheering from the crowds that were gathering outside their town house in Piccadilly.

"Does that mean you're going to be Queen?" asked Margaret.

"Yes," replied Elizabeth coolly, "I suppose it does."

"Poor you!" responded her younger sister humorously as she related the incident to Elizabeth Longford in the early 1980s. But Margaret chose to omit the joke when she re-told the tale two decades later to historian Ben Pimlott. She focused rather on how the new heir had seemed disinclined to jest or dwell upon her dramatic elevation. "She didn't mention it again," the princess told Pimlott.

So what did the 10-year-old Princess Elizabeth know? And when did she know it?

Queen Elizabeth II's first model for what became her destiny was her beloved grandfather, the bluff and bearded King George V (1865-1936). She called him "Grandpa England", which showed how astutely the little girl already grasped the essence of the royal business.

George V was distinguished "by no exercise of social gifts, by no personal magnetism, by no intellectual powers," admitted his official biographer John Gore. "He was neither a wit nor a brilliant raconteur." The old king, in other words, was exactly like most of his subjects. But he had a sharp sense for survival - and also for symbolism.

It was George V who shrewdly jettisoned the royal family's Germanic surname of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha in 1917. So it is hardly surprising that, more than a century later, the world should be in such admiration of the skills that Queen has deployed through her uniquely long and distinguished reign. She learned them first-hand from the House of Windsor's founder.

Sea-loving George V was the source of his granddaughter's famous family nickname 'Lilibet'. In April 1929, on her third birthday, she made it to the cover of TIME magazine as 'P'incess Lilybet'.

Her grandfather's preferred spelling, however, was 'Lilibet' without the 'y', as set out in frequent fond references in his meticulously maintained diary - one of the delights of the Royal Archives at Windsor.

That spring of 1929 the old king insisted that his beloved granddaughter, just three, be brought down to see him at Bognor Regis on the Sussex coast as one of two crucial ingredients to his recovery from a near-fatal lung operation (the second was that "he might be allowed to smoke a cigarette").

It was in these early months of 1929 that George V first shared his hopes that his granddaughter would one day ascend to the British throne.

'You'll see,' he told Lilibet's father, who was visiting him during his convalescence, "your brother will never become King."

"I remember we thought 'how ridiculous'. . ." the Queen Mother recalled in later years. "We both looked at each other and thought 'nonsense'."

But the old king was adamant. "He will abdicate," he insisted to one of his associates - with extraordinary prescience, considering this was seven years before the event.

George V was concerned not only that his eldest son David would sabotage his own reign when he inherited, but also that next-in-line Bertie, himself frail and suffering from lung congestion, would not last the course either.

The old monarch apparently worried that the stuttering Duke of York could collapse under the strain of royal responsibility, so little Lilibet might be thrust upon the throne as a child. In that event, the logical Regent was likely to be George V's stolid third son Henry, Duke of Gloucester (1900-1974).

The possibility of a still-juvenile Elizabeth ascending the throne under the tutelage of her Uncle Henry may simply have reflected the fretting of an ailing king. But staying at Balmoral the previous autumn, Winston Churchill, then Chancellor of the Exchequer (and later the Queen's first prime minister) seemed to endorse the idea that the child might be a future Queen. The young princess, he wrote to his wife Clementine, "is a character. She has an air of authority and reflectiveness astonishing in an infant".

Artist CE Turner captured this image of the young princess with her grandfather King George in Bognor Regis in 1929

As she built sandcastles with her slowly recuperating grandfather, the child had evidently absorbed some royal gravitas from the King Emperor. Before the reign of George V came to an end in 1936, the extraordinary expansion of unsolicited public gifts to his granddaughter - and even requests for the presence of the child at public functions - had reached such a volume that a lady-in-waiting had to be engaged to take care of the affairs of young Elizabeth of York.

At Windsor Castle in the late 1920s, the young Princess Elizabeth (born 21 April 1926) was observed by the Royal Librarian Owen Morshead being wheeled out in her pram to watch the Changing of the Guard, when the officer commanding would march up to salute her smartly.

"Permission to march off, please, Ma'am?"

Sitting up in her pram, the princess would incline her bonneted head, according to Morshead, then wave her hand to give permission. At this tender age the little girl who already grasped the weightiness of her grandfather's national role as "Grandpa England", was clearly developing some inkling of her own as well...

What effect does it have on a three-year-old mind to discover that you only have to wave your hand and nod your head for the band to strike up and the entire platoon to march off at your behest - especially as further signals of your grandeur multiply?

Young Princess Elizabeth on a six cent stamp from Newfoundland in 1932

Soon after her fourth birthday, in the summer of 1930, a waxen effigy of Princess Elizabeth made its debut at Madame Tussauds, seated on a pony. Two years later the princess was featured on a six-cent stamp in Newfoundland - and down near the South Pole the Union Jack was raised over the 350,000 square miles of "Princess Elizabeth Land", claimed by Australia (and a full 100,000 square miles larger than the entire United Kingdom).

"Every time she goes out for a drive in the park,' reported the Belfast News Letter in the summer of 1932, people recognised the six-year-old. "Hats are raised and handkerchiefs raised from all quarters."

For her seventh birthday in April 1933, the princess sent out tea party invitations on her own stationery - blue writing paper embossed with a capital "E" below a royal crown. A crown!

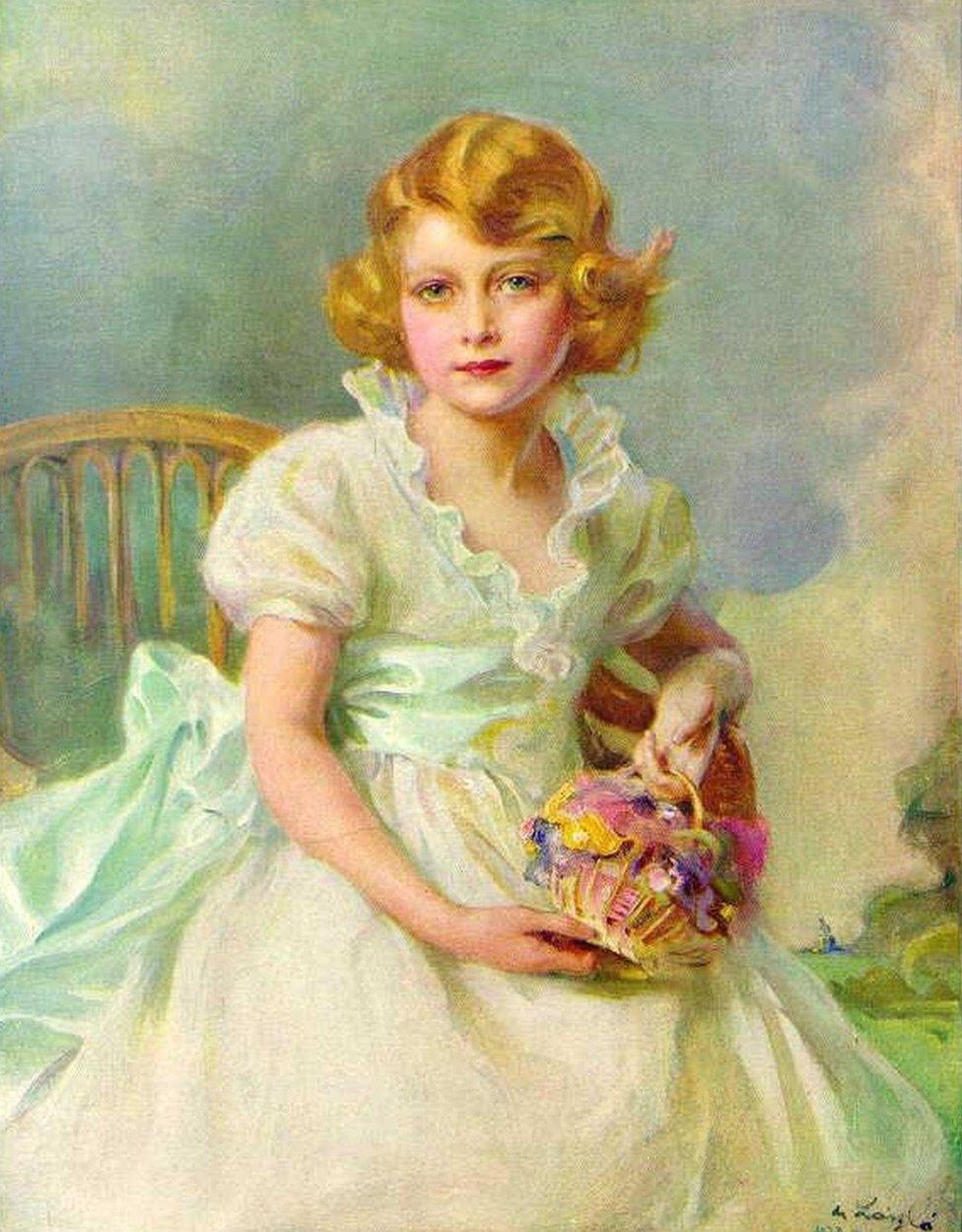

A portrait of the young princess in 1933 by artist Philip de László

Her parents commissioned society artist Philip de László to paint a chocolate-box portrait of their daughter, whom the painter described as "a most intelligent and beautiful little girl... she is enormously popular and... at present looked upon as the future Queen of Great Britain."

This striking news was echoed by a well-informed US report in May 1934 that the future Edward VIII was known to be "lukewarm towards the job for which he was born. Close associates of the Prince have whispered that he does not look forward to being a king with any measure of joy". As a result, the child princess was now receiving "the strict education of one who is regarded as in direct succession to the crown of England".

The likely source of these North American revelations - which were studiously ignored by Britain's still-deferential press - was the princess's recently recruited young governess Marion Crawford, who was described as "very pretty", "very dour" and "very Scotch".

Instantly nicknamed "Crawfie" by her young charges, the governess would become notorious for her best-selling revelations about the upbringing of "The Little Princesses" - in which she disclosed, for example, how she conspired with Queen Mary to subvert their mother's wish that her daughters should spend less time inside the schoolroom.

A story published in the Marysville Journal-Tribune in 1934 - more than two years before the Abdication (the captions got the names of the royal brothers the wrong way round)

Governess and grandmother worked together to inject more rigour into the sisters' education. The severe royal matriarch felt that Princess Elizabeth should only read "the best type of children's books," often selecting them herself - while also dreaming up "instructive amusements" for the future monarch, like visits to the Tower of London.

"It would have been impossible for anyone so devoted to the monarchy as Queen Mary," recalled her friend the Countess of Airlie, "to lose sight of the future Queen in this favourite grandchild."

Grandpa England, meanwhile, set more simple targets. "For goodness' sake," he boomed at the governess, "teach Margaret and Lilibet to write a decent hand - that's all I ask you! None of my children could write properly. They all do it exactly the same way. I like a hand with some character in it."

Foreign newspapers noted how the young princess's chances of becoming "Queen-Regnant" were now better than had been those of the eight-year-old Queen Victoria a century earlier - the daughter of a fourth son with two uncles ahead of her. Small wonder that these grand expectations should not rub off on the alert and knowing Elizabeth.

"If I am ever Queen," she told Crawfie, "I shall make a law that there must be no riding on Sundays. Horses should have a rest, too."

Queen Mary sensed the danger. Noticing how her granddaughter was wriggling impatiently on one excursion at a concert, the Queen asked if she would not prefer to go home.

"Oh no, Granny," came the reply, "we can't leave before the end. Think of all the people who'll be waiting to see us outside" - whereupon Granny immediately instructed a lady-in-waiting to escort the child out by the back way and take her home in a taxi.

Queen Mary did not want her elder granddaughter getting addicted to adulation. The Queen and her husband understood how modesty, humility and a sense of service constituted the price that royals had to pay for their grandeur in a democratic age. Duty was their watchword, and they both passed this crucial lesson on to their granddaughter - that she was less important than the system. They made sure Lilibet grew up a team player.

Prince William is said to have wanted his son Prince George to enjoy a few years of relative normality before being told his future

From all the signs and signals, it does seem likely that the future Elizabeth II had acquired a realistic idea of what lay ahead for her by the age of seven - at least three years before the abdication.

Interestingly, the age of seven was when Prince William is said to have revealed the same challenging reality to his son George - at the latest moment before the boy was likely to be confronted with the truth in his London school playground.

Like Charles, his father, William has voiced mixed feelings at being saddled with knowing his regal destiny from his earliest awareness. He wanted George to enjoy just a few years of relative normality - and maybe that instinct for the normal is what the Queen's early succession-free years granted her. She might have been elevated to the role of captain, but she never forgot she had started as a player in the team.

Coming to the throne in 1952, the Queen would preside over a reign of two halves - relatively humdrum and even drab for nearly three decades, before crackling into life-on-the-edge with the troubled 1980s marriage of Charles to Diana, the gift that kept on giving to the voracious late-century media.

This was when the childhood lessons the young Elizabeth had absorbed from her grandparents came into play. The Queen needed all the steady humility she could muster to withstand the avalanche of abdication-like tremors: Charles, Diana, Camilla, the Windsor fire, Andrew-with-Fergie, Andrew-without-Fergie - with the unexpected tweak-in-the-tail delivered by the departure to the US of grandson Harry in 2020. It was one crisis after another - and through it all, the monarchy prevailed in her safe hands.

A dry sense of humour helped. In 1992 the Queen disarmed the disaster of the Windsor Fire and the breakdown of three of her children's marriages by resorting to some facetious dog Latin - 1992 had been her "Annus Horribilis", she explained with a smile.

"Oh dear," she enquired when an embarrassed Labour minister Clare Short had to stop her mobile phone from ringing during a Privy Council meeting. "I hope it wasn't anyone important?"

From an early age the sharp-eyed and sharp-thinking Queen Elizabeth II seems to have grasped the comedy of the royal show in which she would be destined to play a leading role.

"Let us not take ourselves too seriously," she declared in her Christmas broadcast for 1991. "None of us has a monopoly on wisdom."

The young princesses Elizabeth and Margaret with their parents and dogs at Windsor in 1936

In 1933, according to royal legend, Lilibet confidently informed her sister Margaret, born in 1930, "I'm three and you're four."

Young and confused, but still able to do the sums, Margaret responded: "No, you're not. I'm three, you're seven!"

It took time to dawn on Margaret that her elder sister was not talking about age. She was referring to the two girls' respective positions in the order of succession after their grandfather - Uncle David, one; Papa, two; and Lilibet, three. The seven-year-old was right up to speed with what the rest of the world was starting to think.

After the abdication and having been moved up two rankings to face the challenge of being number one in the line of succession, the 10-year-old princess was described by her grandmother Lady Strathmore as "ardently praying for a brother".

But there was no baby brother coming to the rescue. The little girl raised among her horses and dogs now had to prepare herself for the challenge of eventually becoming "Grandma England" - and "Grandma" of Wales, Northern Ireland and Scotland too.

Robert Lacey is a British historian and biographer who has made a particular study of Britain's modern constitutional monarchy. His biography Majesty: Elizabeth II and the House of Windsor was published in 1977. Since 2015 he has been historical consultant to the Netflix TV series The Crown.