Care-worker shortage: Woman appalled by lack of support for dying mum

- Published

Cathy says the struggle to find care for her mum Maureen left her 'desperate and appalled'

"Good care is what you would want for yourself and your parents... and it's not there. It's totally broken."

Cathy, who asked not to use her full name, says finding care for her 83-year-old mum Maureen was "a nightmare".

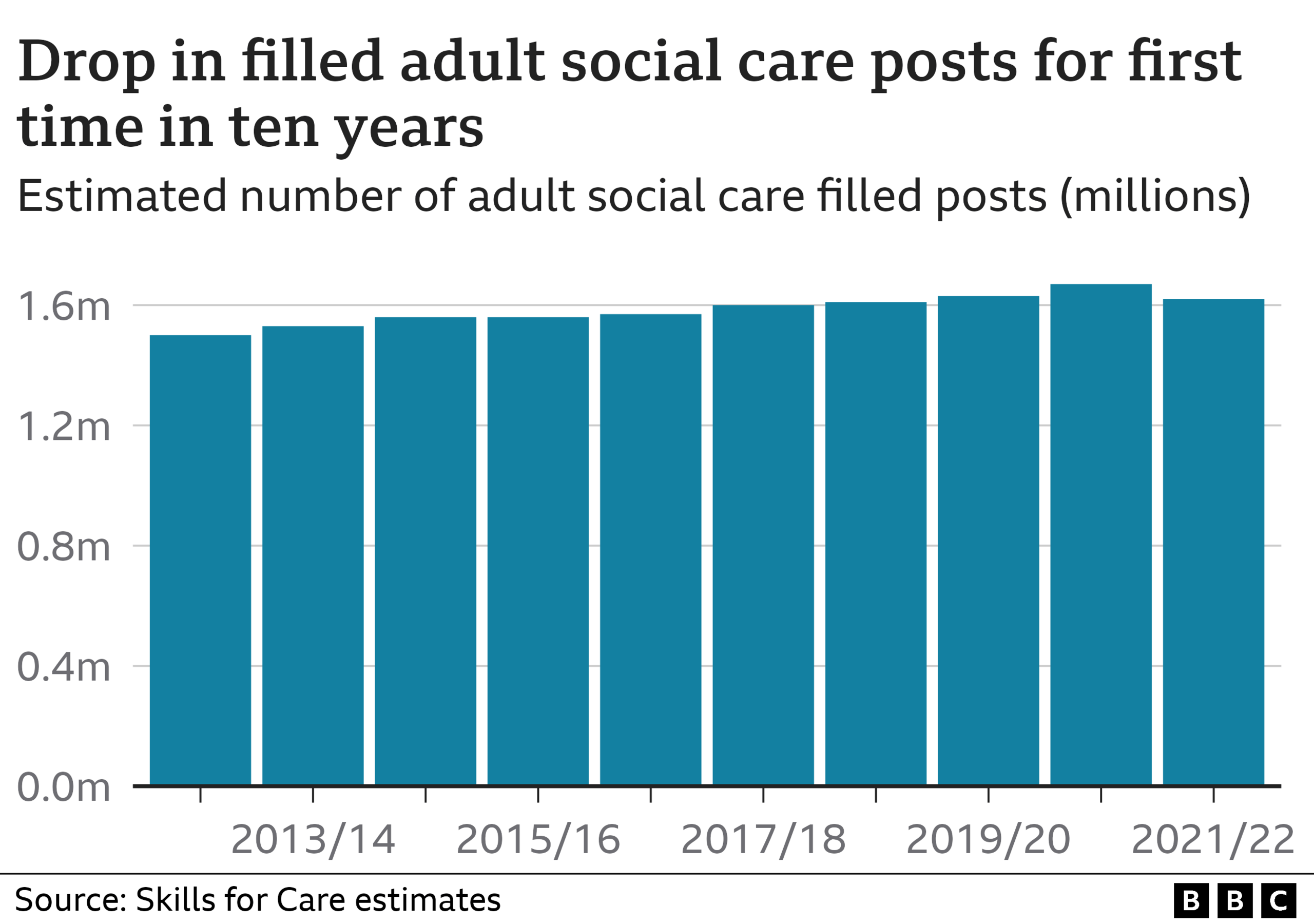

They are not alone - new figures show the number of care workers in England has fallen for the first time, leaving more people without support.

The number of empty care jobs both rose by 52% in a year says the industry body, Skills for Care.

Maureen died of liver cancer last month, on the same day as the Queen, her last months shaped by failings in the health and social care system.

The latest annual Skills for Care workforce analysis, external found in the year to March there were:

a total of 1.79 million posts in adult social care

of these 1.62 million were filled, leaving 165,000 vacant - a rise of 52% on the previous year

the number of filled posts fell by 50,000 compared with the previous year - the first drop ever

These figures refer both to staff in care homes and workers who support people in their own homes.

The fall is due to problems with recruiting and retaining staff - but, at the same time, the demand for care has risen, says the report.

It warns the shortage of care workers will increasingly affect people who need support, and their families.

'Desperate and appalled'

Maureen's family has already felt that impact.

Early on in her illness, Maureen was told the struggle to find care staff would be particularly difficult because she lived in a rural area.

On her own at home and without care, she had a series of falls which put her in hospital.

Maureen in happier times

Once, she was discharged from a hospital emergency department to an empty house at 03:00 and, within hours, had fallen again.

Her condition deteriorated and she became eligible for NHS-funded end-of-life care visits.

Even so, she was stuck in hospital for more than a week after doctors said she was ready to go home, waiting for the authorities to find a care company able to visit her four times a day.

Finally her daughter Cathy, "desperate and appalled", found care providers herself and persuaded the NHS to pay for them.

Cathy says the experience, when the family should have been focusing on their mother's last few days, was "shocking".

Rising demand

The report warns experiences like this will become more common as the population ages, and employers will need to fill about 480,000 more posts by 2035.

On top of that, more than a quarter (28%) of the existing workforce are aged over 55 and likely to retire within 10 years.

In addition:

four out of five jobs in the wider economy pay more than the median pay for care workers

the average care worker gets £1 an hour less than a newly hired NHS healthcare assistant

care workers with five years experience get just 7p an hour more than new recruits

Separate research from the Health Foundation charity, also published on Tuesday, found one in five residential care workers in the UK were already living in poverty before the cost-of-living crisis, compared with one in eight of all workers.

Minimum wage

James Waterhouse, from Rotherham, worked for about 10 years in homes for people with dementia.

For James, helping "the most vulnerable people in society, going through probably the worst disease you can get... and being able to bring something good to their lives... it does make it worthwhile".

James Waterhouse had money worries on a care worker's wage

Until last year he was a senior carer, in charge of administering medication for up to 40 people overnight - and earned the minimum wage.

He had money worries and felt he couldn't progress in life. Finally he left for better-paid work.

"It just adds to the stress within the job... so you add those things together and on many occasions, not only myself but other carers, you just end up breaking down at work."

Long-term thinking

Skills for Care chief executive Oonagh Smyth is calling for "a step change" in how we value social care.

She wants better terms, conditions and career development for care workers "to make it easier for the people who love working in social care to stay".

"We need to think now about the long-term workforce requirements... so that we have enough people with the right skills and knowledge to meet increased demand," she said.

The government points out the report only covers the period until March and says, since then, tens of thousands of care workers have been appointed from overseas after the role was added to the shortage occupation list.

"We're investing in adult social care and have made £500m available to support discharge from hospital into the community and bolster the workforce this winter, on top of record funding to support our 10-year plan set out in the People at the Heart of Care White Paper, external," said an official.

The official said a £15m international recruitment fund and a new domestic campaign would be launched soon.

The Skills for Care report is based on analysis of figures collected from 20,000 employers.

Have you been affected by the issues raised in this story? Share your experiences by emailing haveyoursay@bbc.co.uk, external.

Please include a contact number if you are willing to speak to a BBC journalist. You can also get in touch in the following ways:

WhatsApp: +44 7756 165803

Tweet: @BBC_HaveYourSay, external

Please read our terms & conditions and privacy policy

If you are reading this page and can't see the form you will need to visit the mobile version of the BBC website to submit your question or comment or you can email us at HaveYourSay@bbc.co.uk, external. Please include your name, age and location with any submission.

Related topics

- Published19 July 2022

- Published6 October 2022

- Published20 November 2022