Tommy Jessop: Why I investigated hospital care for people like me

- Published

People with a learning disability are more than twice as likely to die from avoidable causes than the rest of the population. Actor Tommy Jessop and BBC Panorama investigated some of the stories of families who say they were let down by their medical care.

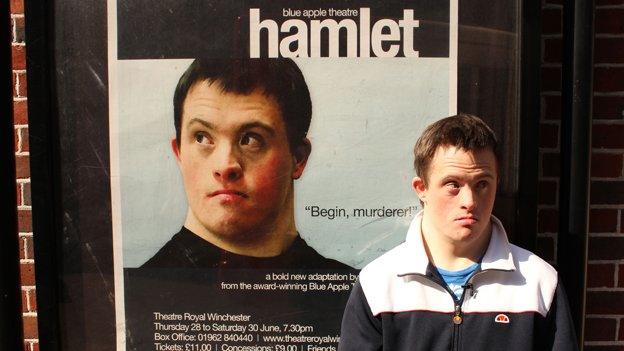

Tommy Jessop is an actor and campaigner who wants to use his voice to make sure people with a learning disability are heard.

He's known to millions for his role as Terry Boyle on the TV series Line of Duty. He also has Down's syndrome, which puts him among the 1.5 million people with a learning disability in the UK at risk of having their lives cut short by illnesses that can be treated or prevented.

For a BBC Panorama, he has been investigating the failures of healthcare which contribute to people with a learning disability having a life expectancy 20 years shorter than non-disabled people.

He found cases where disabled people were not listened to, where they were neglected, and where families had to fight for appropriate treatment instead of their loved ones being allowed to die.

"Being in Line of Duty made people listen more and I had lots of invitations to speak up. It is about time people really should start listening to us and see how we really feel," Tommy says.

"People with a learning disability used to be hidden away, because people didn't believe in us. But our lives truly are worth living and medical care should be better for all of us."

Tommy says he has always had good care from the NHS but that's not always the case for other people like him.

A report by researchers at King's College London and other universities, external found that in nearly half of cases where a person with a learning disability died before the age of 75, the cause was a preventable or treatable illness. For everyone else, that figure was 22%.

Reviewing more than 3,500 deaths of people with a learning disability, the report found that in nearly a third of cases there was no evidence of good practice.

Tommy and Panorama examined thousands of coroners' reports from the past nine years. They also heard the stories of four people with a learning disability who had been affected by poor care.

Chloe died in hospital at the age of just 27. She had a learning disability and lived with a serious muscle condition called myotonic dystrophy.

In April 2019, she became very ill and was admitted to Queen's Hospital in Romford, where a scan revealed possible signs of cancer. Chloe was agitated and in pain, and struggled to communicate how she felt, her aunt Lisa told Tommy.

Chloe Every died in hospital at the age of 27

Chloe was given morphine, which can cause breathing problems for people with her muscle condition. Three days later, she went into cardiac arrest and was resuscitated.

After five more days, she was moved into a general ward. Specialist learning disability nurses were not involved in her care there. She died in the early hours of the morning.

An independent investigation found the transition to morphine may have contributed to her collapse and that doctors failed to recognise that her health was getting worse. "Chloe's voice was not always heard during her stay," the report found.

Barking, Havering and Redbridge University Hospitals NHS Trust, which runs the hospital where Chloe died, said it was extremely sorry she did not receive the high level of care she deserved, but that it did not find evidence that the morphine caused her cardiac arrest.

It said it had made improvements to ensure patients with learning disabilities are listened to and cared for better.

Tommy says many of the stories were about a failure of health professionals to listen to and understand disabled people.

He met the family of a woman with Down's syndrome, Julie Taylor, who was admitted to Stepping Hill Hospital in Stockport. Before arriving in hospital, she had stopped eating and drinking, and lost nearly three stone.

It took two days before the hospital adjusted their care to take account of her disability.

Her brother, Peter, visited and found her bed soiled and dry vomit in her hair. Julie lost another two stone in hospital and was at high risk of malnutrition. But she was never referred to the nutritional team.

She caught chickenpox and, too weak to fight the infection, Julie died days later, aged 58.

"I think she was a nuisance to them and they hadn't got the facilities or the trained staff to deal with people with a learning disability," Peter tells Tommy.

The number of learning disability nurses in the NHS has fallen from 5,500 in 2009 to approximately 3,200.

Cat McIntosh, a community learning disability nurse who cared for Julie before she went into hospital, said she thought she had experienced discrimination.

"It felt to me as though people weren't prepared to make the effort or show her the same level of care that we would if maybe she didn't have the diagnosis and the labels," she says.

Stockport NHS Foundation Trust offered its "sincere condolences" to Julie's family and accepted there were lapses in procedures in her care, but it strongly denied that staff discriminated against her.

Tommy also met a mother who had to fight to get life-saving care for her son.

Robert, who has the genetic disorder Fragile X syndrome, was treated for testicular cancer two years ago. The tumour was removed but the cancer had spread and the recommended treatment required 72 hours of chemotherapy.

His mother, Sharon, says it was impossible for him to sit still long enough for any invasive treatment, but the hospital at this point offered no alternative.

They said Robert would have to go into end of life care.

"They kept saying there was nothing that they could give him," Sharon says. "I was pleading."

Panorama: Will the NHS Care for Me?

Tommy Jessop investigates why people with a learning disability are more than twice as likely to die from avoidable causes than the rest of the population.

Watch now on BBC iPlayer (UK Only)

Also on 10 October on BBC One - 20:00 in England, 22:40 in Wales and Northern Ireland, and 23:40 in Scotland.

She put out a call for help on social media and got a lawyer and a second medical opinion. At that point, the hospital convened a meeting and suggested a different course of chemotherapy.

Robert has now made a full recovery, but his treatment by the hospital left Sharon "heartbroken".

"Is it because I've kicked up a fuss? Is it because I've got a solicitor involved? You're dealing with people's lives," she says.

Sharon was only able to tell her story openly because the BBC went to court to challenge an order protecting her identity.

Newcastle Upon Tyne Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust said it worked hard to support Robert and his family.

It said that it held a "best interests" meeting for Robert, where agencies formally decide the best options for someone who does not have the capacity to decide themselves, as soon as concerns were raised. But it acknowledged the meeting should have been held earlier.

Tommy Jessop at the launch of Bafta Elevate, which aims to help support individuals from under-represented backgrounds

Treating people with a learning disability can be challenging for doctors and nurses in a busy environment like a hospital because it can take a little longer, says Tommy.

After investigating these cases, he says some hospitals might benefit from staff who understand the issues of people with a learning disability and can communicate when people can't explain very well.

Tommy says that staff would be more likely to get the right diagnosis and not just attribute the symptoms to their disability. Doctors and nurses should ask disabled people about their symptoms directly and not just talk to their parents or carers, he says.

"Now more than ever people with a learning disability want to be heard," Tommy says. "And we say we should be treated like everyone else."

- Published13 November 2020

- Published4 May 2018

- Published3 February 2014