Smugglers just part of wider migration problem for UK

- Published

The UK is giving France more money in an attempt to reduce the number of migrants crossing the English Channel. But will it make a difference?

Under the new agreement, the UK will pay France £63m - up from £55m last year - to patrol its coastline on the lookout for people-smuggling gangs.

That extra £8m will see the number of officers patrolling France's beaches go from 250 to 350 - a considerable leap in resources that could be a sign of the challenges faced.

The UK-France package will also cover further investment in drones, night-vision equipment, sniffer dogs, CCTV and port security.

Since 2018, National Crime Agency officers have been working with their French counterparts on joint intelligence operations.

That deal paved the way for the creation of the UK-France Joint Intelligence Cell in 2020, which has so far dismantled 55 organised crime groups.

The new agreement means that for the first time, specialist UK officers will be stationed alongside French teams in France.

So what are the challenges?

The first issue faced by the two nations, as reported by the BBC's Paris correspondent Lucy Williamson, is not just organised crime - but geography. France's northern coastline is covered with dunes, foliage and hundreds of World War Two bunkers - all places for migrants to hide from the authorities.

Secondly, what will the British actually be able to do? The new announcement shifts some UK specialist officers closer to frontline decision-making - but they will only be observers.

So even if more boats and smugglers are intercepted, UK officers can't tell the French what to do with individual migrants.

The UK's strategy seems to be to chuck money at intercepting smuggling gangs, in the hopes of building a clearer picture of how they work and disrupting their business model.

Suella Braverman and France's Gérald Darmanin with their joint migrant patrol deal

This tactic - of putting a dent in the profits of people smugglers - echoes the UK's approach in other fields of organised crime. But even if operations do manage to cut the supply of small boats, there is the equally large challenge of demand to deal with.

Many campaigners argue that the number of Channel crossings would fall a great deal if the government created more safe routes for refugees to come to the UK.

People seeking protection cannot go to their nearby British embassy and ask for help - and they can't board a plane to the UK without a visa or permission to enter.

People smugglers step into that space and offer a dangerous alternative to those who can pay.

The same smugglers also offer deals to economic migrants and to traffickers conning people into modern day slavery.

In short, behind each boat making the perilous journey across Channel, there is a thriving global eco-system of criminal profits.

That is why many critics argue the UK needs to be part of a continental-wide migrant management plan. But if Brussels were to devise a new scheme tomorrow, it may not include the UK.

That is because during Brexit, London declined to be part of a future asylum and migrant deal with the EU. There is not even an agreement to send people back to France.

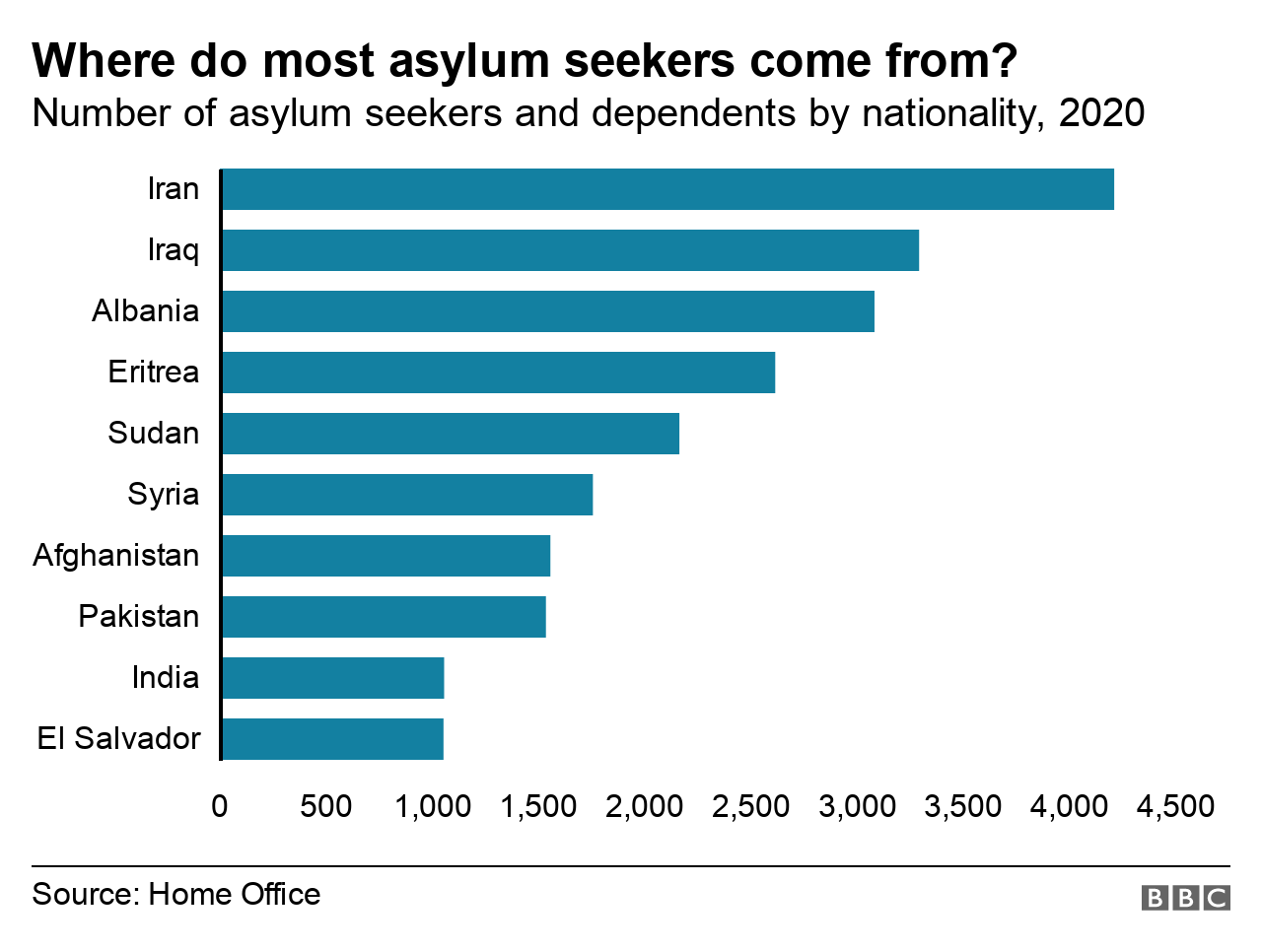

The new agreement with France fails to address a major bureaucratic workflow crisis which can be seen in the statistics.

When someone arrives in the UK, the time the Home Office takes to deal which each migrant's case is very slow.

So slow in fact that the UK Refugee Council says there are 120,000 people still awaiting a decision - and a third have been waiting up to three years. Those backlogs were growing long before the current spike in migrants coming to the UK.

Charities are not alone in raising these concerns. Labour MPs have been saying it - and Natalie Elphicke, the Conservative MP for Dover, agrees.

The Home Office is now trying to address these criticisms by rolling out a new way of deciding asylum applications.

A group of people thought to be migrants are brought in to Dover, Kent, aboard a Border Force vessel

A pilot scheme trialled by a Home Office casework team this summer found that the amount of time asylum seekers wait for an interview could be cut by 40%.

But even if decisions are made faster, there is a second issue causing a backlog - removing failed asylum seekers out of the UK. This all depends on the government getting better deals with other countries - including the EU - to take people back.

Until there are major improvements in applications and removals, migrants who want to come to the UK may calculate that they are unlikely to be forced to leave if they ever reach our shores.

- Published14 November 2022

- Published12 November 2022

- Published12 November 2022

- Published2 November 2022

- Published8 November 2022