Mental health: NHS crisis lines failing to answer suicide calls

- Published

Hannah says she had to call seven times, over two days, to get through to a crisis line

Suicidal patients in England are being put at risk of serious harm, with one in five calls to NHS helplines going unanswered, BBC research shows.

One caller said after repeatedly trying to get through, staff eventually told her to "think happy thoughts".

Coroners have expressed fears over how patients are assessed. One man who died told staff he wanted to end his life, but was not referred for support.

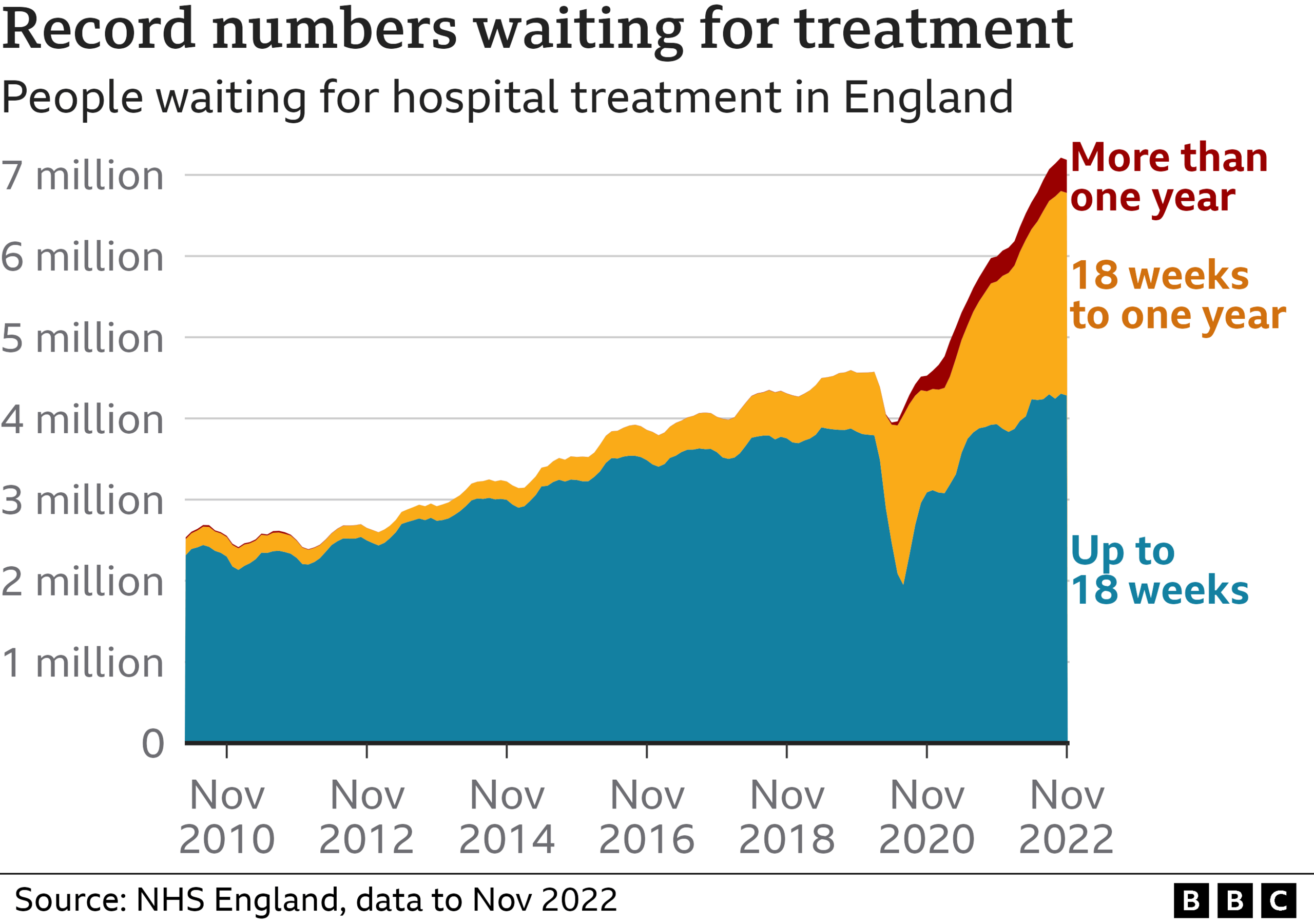

NHS England said crisis lines had seen "record demand".

It said it had made £7m available to local areas to improve their crisis lines, to "ensure that everyone receives the support they need".

Run by NHS mental health trusts, crisis lines receive over 200,000 calls each month across England.

They aim to signpost patients to services, and provide access to urgent mental health support by phone for adults - and in some areas under-18s - at high risk of suicide. They were seen as key to making mental health support more accessible during the pandemic.

But figures collated by the BBC through Freedom of Information requests, from 29 of the 47 mental health trusts with crisis lines, show that at least 418,000 calls went unanswered in 2021-22.

That means 20% of calls to these trusts weren't answered - with some areas performing far better than others.

In 10 trusts, some people waited more than an hour for their call to be answered.

The BBC has spoken to more than a dozen crisis line callers who say their safety or their lives have been put at risk.

Hannah, who has been diagnosed with borderline personality disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, depression and anxiety, says on one occasion when she was suicidal it took her seven calls - across two days - to get through.

"I've literally been crying my eyes out and I've left a message on the answer phone and no-one's ever got back to me.

"Your brain already makes you feel that you're alone. And then to have the people that are meant to care not answer, it makes it 10 times worse."

When Hannah did get through to the helpline, she said she explained she no longer wanted to be alive, but was told to "think happy thoughts and read a book" - before the staff member blamed her for "not wanting to help yourself" and ended the call.

Hannah says she took herself to A&E, a decision she believes may have saved her life, and was later sectioned.

South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust has since apologised, saying Hannah's calls should have been returned and the advice given by staff was "not appropriate". It said improvements had been made.

Fewer than one in six trusts that responded to the BBC's request for data said all their crisis line staff were qualified mental health professionals.

Professor Sonia Johnson says it is a "major problem" if callers are unable to access helplines in a timely manner

Former staff members at three different NHS Trusts have told the BBC that after being hired, they were not given training on assessing or supporting patients.

"You're expected to learn on the job, which is disappointing when you're dealing with people's lives," said ex-employee Sophie - not her real name - who left her role in mid-2022.

She was a call handler whose role it was to assess patient risk and - where someone was in need of urgent support - pass their call to a "responder", who in most cases would be a qualified mental health nurse.

But Sophie said that because of staffing pressures, "very often" the responders were busy, and so suicidal patients would be asked to wait for help.

"We would then try to call them back within 15 minutes. But it wasn't always possible."

Staff were told to limit the time spent speaking to callers to meet demand, she said, but this detracted from their ability to provide compassionate care. "You forget about the human factor."

If you've been affected by self-harm or emotional distress, help and support is available via the BBC Action Line

In 2022, coroners investigating deaths published two Prevention of Future Deaths reports - written to alert the wider healthcare system to issues of concern - that highlighted concerns about crisis lines.

In one case, the coroner found the individual in question had called his local NHS crisis line and described himself "as 'suicidal', wanting to die… [and] scared that that he might try and take his own life".

The caller was not recognised by the service to have been in a mental health crisis, the inquest found, and no referral for crisis or urgent support was made. He was found dead by loved ones the following day.

In his report, the coroner found there had been "difficulties in recruitment" of staff, which were associated with levels of service funding.

He said call handlers did not always have enough time to effectively assess patient risk, which "creates a risk of future deaths" and was a concern "experienced nationally".

Former call handler Sophie said staffing pressures meant suicidal patients were asked to wait

The trust acknowledged the "advice given and lack of onward referral appeared to be an inadequate response", the report said.

Prof Sonia Johnson, an expert in community psychiatry at University College London, believes staffing pressures in the wider mental health system have led to demand for crisis services among patients unable to get the long-term support they need.

She said it was a "major problem" if such callers were unable to access helplines in a timely manner.

"The purpose of crisis lines should really be to make access to support easy, to make it easy not to go to A&E."

"The great pressures that there are on [A&E] services at the moment make it doubly important to have alternatives."

A Department of Health and Social Care spokesperson said by 2024 its workforce investment "will deliver an additional 27,000 mental health professionals and give two million more people the help they need".

In Scotland and Wales, mental health support is available through NHS 111. Northern Ireland has its own crisis response hotline, Lifeline.

Related topics

- Published7 December 2022

- Published20 April 2021

- Published17 March 2021

- Published21 February 2020