Nicola Bulley: Why can it take so long to find bodies?

- Published

Dive teams used sonar to search for Nicola Bulley's body on the River Wyre

After three heartbreaking weeks for Nicola Bulley's family, her body has been found.

A question many have been asking is - could she have been found sooner?

Contrary to the conclusions of social media sleuths, finding bodies in water is one of the toughest challenges in policing.

Two terribly sad cases within weeks of each other in York in 2014 demonstrate how long it can take for bodies to be found - and how far they can move.

Megan Roberts, a 20-year-old student, died after falling into the River Ouse after becoming separated from friends on a night out. Her body was found six weeks later five miles (8km) downstream.

Just before Ms Roberts was found, Ben Clarkson, a 22-year-old who worked in a music shop in the city, fell into the River Foss and drowned. His body was recovered three weeks later, nowhere near the most likely point he entered the water.

Without getting into scientific detail that some may find distressing, bodies do not stay in one position at the bottom of water, near where they were last seen.

Over time they will resurface, unless they have become completely lodged in an unreachable underwater location.

If the water is tidal or has currents, and the victim is not found in the immediate days after their disappearance, their body could ultimately move far away from the centre of the search.

"It's complex searching water," Julie Mackay, a former detective from Avon and Somerset Police's cold-case unit, told BBC Radio 5 Live.

"The fact that there is a lot of debris in the water and people are not found immediately is not that uncommon.

"Because this case has had so much scrutiny then every little step is micro-analysed. 'Why didn't we find her just a mile down the river? Why is it taking so long for her to appear?'

"But it's not that unusual and I'm sure that there'll be a review of everything the police have done, and from the review where there's learning and good practice to come out, that will make them better in the future."

Searching underwater is difficult and often inconclusive work

The College of Policing - the national standards-setting organisation for forces in England and Wales - oversees the training for searching, which includes specialist skills for missing persons.

Licensed search officers (LSOs) typically work in pairs and must use textbook-approved techniques to ensure that any search meets national standards.

They must be as sure as they can be when they leave an area that there is nothing evidential that they have missed.

They have to keep accurate records of a search's progress. Officers must also take part in at least four significant searches a year in order to remain qualified.

Police Search Advisers, the next step up, have to do yet more training and they are expected to take part in both a nationwide sharing of skills and experience and, crucially, peer review each other's operations, whatever the outcome.

There has been a lot of focus on Peter Faulding, the private search contractor who works with police forces around the UK.

His team volunteered to help Lancashire Police, and he said on joining the search: "If Nicola is here, I'm happy we will find her, if she's in the river.

"If we can't find her in the next three or four days in this river... then I'm confident that she's not in this stretch of river."

Mr Faulding has since defended the work he carried out in a statement on Facebook.

He said his company had indeed searched the part of the riverbed where the body was later found in reeds.

But it is important to understand what kind of search Mr Faulding's team were conducting.

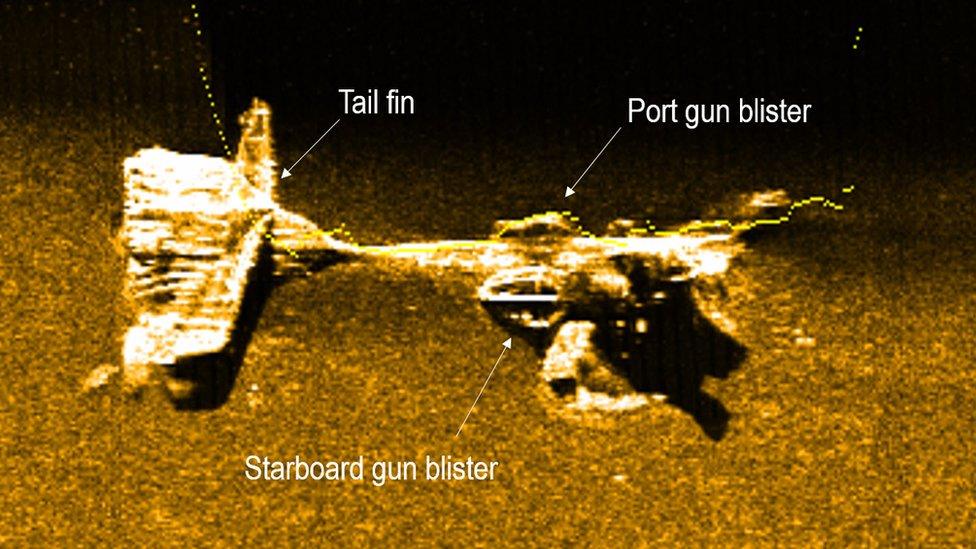

They were using a piece of kit called side-scan sonar which is regularly used in searches to build up a picture of a river bed.

Sonar scanning is now so sophisticated it provides the operator with detailed outlines of every object at the bottom of a body of water - such as this image of a World War Two seaplane that was discovered in Lough Erne, County Fermanagh, in 2019.

Famously, a retired couple with science backgrounds have used their own side-scan sonar to assist missing persons inquiries, external across the United States.

Crucially, Mr Faulding says sonar would never be used to search reeds by the side of a river because it would not penetrate them.

Such a search would have to be a manual riverbank and wading search.

"My previous comments saying that if Nicola was in the river, I would find her, still stand," the forensic search expert said.

We do not know if the police or any other team carried out that manual search of the critical area or had been tasked to.

And it is not clear whether Lancashire Police considered other technologies.

Ground-penetrating radar, deployed under a small boat, can detect objects that have sunk into soft sediment.

One of the UK's leading academics in geo-forensics has shown how this technique, combined with sonar and dogs detecting scent from decaying bodies, can lead to the recovery of a victim of drowning, external.

The more proven technology that can be deployed, the more time is saved for focused fingertip searches by divers.

But sometimes it still takes weeks and weeks to get answers. And sometimes, tragically, no answers can be found at all.

WHAT IS AN AGLET?: Eight things you use every day but never knew their name

FROM STARTER TO SUPERSTAR: Mary Berry comes to the rescue of hopeless novice cooks

- Published21 February 2023

- Published21 February 2023

- Published17 February 2023

- Published15 February 2023