King Charles: Why does the monarch need a coronation?

- Published

As many before his have done, King Charles' coronation will feature a medieval oath, a holy oil poured on to a 12th Century spoon, and a 700-year-old chair

King Charles III's coronation on 6 May is likely to showcase the sort of lavish royal pageantry the British are famous for. But it is also a deeply religious occasion steeped in centuries-old traditions that, to some, might seem out of place in 2023. Does such an event hold the significance it once did and does the monarch need one at all?

In just a few weeks' time, millions of people across the UK will witness a rare event.

While we might be used to the pomp, crowds and street parties that accompany royal celebrations and jubilees, it's been 70 years since we've seen a coronation. This is an entirely different affair, littered with curiosities: a medieval oath, holy oil poured on to a 12th Century spoon, and a 700-year-old chair housing a stone that supposedly roared when it recognised the rightful monarch.

Some experts liken a coronation to a wedding - but instead of a spouse, the monarch is being married to the state. The 2,000 people who will watch King Charles crowned at Westminster Abbey will be asked whether they recognise him as monarch. He will then be given a coronation ring and asked to swear an oath.

If all of this sounds like something from a bygone age, it's because coronation ceremonies in the UK have changed little over the past 1,000 years. By law, there's no need for them, as the monarch succeeds automatically on the death of their predecessor. But they're a symbolic gesture that formalises the monarch's commitment to the role, says Dr George Gross, who is leading a research project on coronations , externalat Kings College London.

He believes the promises a monarch makes to "uphold law and justice with mercy" in a public statement is a unique and special moment.

"In an uncertain world where leaders break international rules of law all the time, our monarch has to say 'these are the fundamental things that matter', and that doesn't jar to me."

The coronation spoon was first recorded in 1349 among St Edward's Regalia in Westminster Abbey, when it was already considered "antique"

Bringing together old and new?

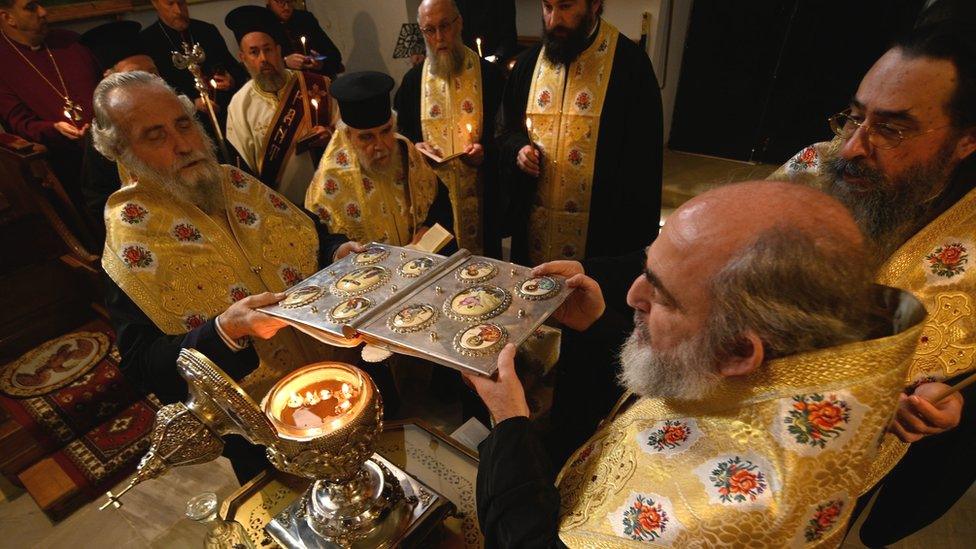

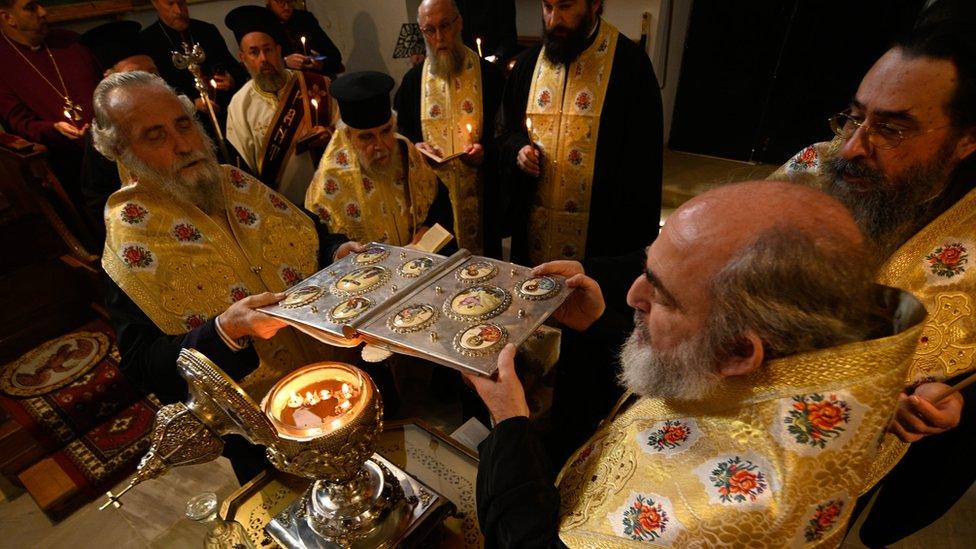

What happens next perhaps sums up what the coronation is: a fundamentally religious occasion. An outline of the cross is traced on the monarch's head, hands and chest using a consecrated oil, dispensed on to the medieval spoon.

The anointing process elevates "the monarch almost to a priest", says Dr Gross, and signals the monarch's role as head of the church.

"It's an Anglican ceremony and the anointing is essential to that as the conferment of God's grace on the monarch," says Dr David Torrance, who has written a parliamentary research paper on coronations., external

"But it's also the Church of England reminding everyone they're one of the established churches of the UK and the monarch is its supreme governor."

This moment is done in private because it is seen as an intimate moment, and for practicality reasons since the monarch wears fewer clothes at this point, says Dr Elena Woodacre, director of the Royal Studies Network. Cameras are likely to pan away as they did when Queen Elizabeth was disrobed of her cloak and jewellery during her televised coronation in 1953.

A canopy was placed over the Queen before she was anointed at her coronation in 1953

Read the latest from our royal correspondent Sean Coughlan - sign up here.

Instead of using the oil from the previous coronation - as some monarchs have done - a fresh batch has been made this year. Previously it contained animal products like civet oil and ambergris, which is found in sperm whales, but this vegan and cruelty-free version is made partly from olives. In a possible nod to other faiths, they were grown at the Monastery of Mary Magdalene in Jerusalem, where the King's grandmother Princess Alice is buried.

But the choice of oil is also in keeping with "modern sensibilities", says Dr Woodacre, adding that it "blends tradition and continuity with adaptation and change" at a moment where some question whether the monarchy still has a place.

"The coronation is the King's chance to plug into the power of the past and shape his future. All of these ancient traditions like the Abbey and the use of the spoon help reinforce his position."

The oil for this year's coronation was made from olives grown in Jerusalem, where it was also consecrated

Do we care about tradition?

Graham Smith, from pressure group Republic which campaigns for an elected head of state, questions whether tradition is a valid argument when coronations have "changed in scale, scope and content every time".

"Most people can't remember the last time, so it's not a tradition that means anything to anybody," he says. "It has no constitutional value, it's not required, and if we didn't do it, Charles would still be King."

Indeed, a monarch doesn't need a coronation to rule and a handful have done so without one, like Edward VIII, who abdicated before his. European monarchies got rid of coronations long ago and public opinion suggests interest is perhaps waning in the UK.

A recent YouGov poll , externalfound 48% of respondents were not very, or at all, likely to watch the coronation. Another, conducted around the time of the Queen's platinum jubilee, found that while six in 10 supported the monarchy, the majority of Brits felt the Royal Family was less important to the country than it was in 1952, external.

Thousands lined the streets of London on the day of the Queen's funeral

Stephen Evans, chief executive of the National Secular Society, says the UK's religious landscape for example has "changed beyond all recognition" since the last coronation in 1953 and "many will feel alienated by an Anglican ceremony".

Dr Torrance agrees central aspects of the ceremony might have been familiar to people then and perhaps less so now. But he says statistics show congregations in London are increasing and many Anglican churches are very busy.

"When the Queen died we had a lot of religion mingled with ceremony. I think the Palace was surprised by the public response… a lot paid quite close attention," he says. "If there's an effort to make the coronation less exclusively Anglican, it might be taking into account that the UK now has a proliferation of different faiths."

A 21st Century coronation?

It remains, however, that the essential part of the ceremony is tied to one faith, says Prof Anna Whitelock, director of the Centre for the Study of Modern Monarchy.

"The problem is that at the heart of it is the anointing [and] the oath which is about upholding the Church of England. The fact is you can't change the fundamental parts of the coronation, which is exclusive, it's not diverse, it's about privilege and everything that a multi-faith, multi-ethnic Britain isn't about."

Prof Whitelock agrees that attempts have been made to modernise the coronation such as making it smaller in comparison to the last one, commissioning new music, and involving diverse guests, "but it's an attempt to change the style [when] you can't change the substance".

She suspects any meaningful change would require a major overhaul, like disestablishment of the Church of England or a referendum on the monarchy, neither of which she expects to see any time soon.

"The monarchy's legitimacy is based on tradition and continuity, so I think if Prince William was to do away with the coronation it would be seen as too much and undermining of the institution, and I don't think we're there yet."

It is thought the coronation guestlist will number about 2,000, in comparison to the 8,000 that attended the Queen's

Dr Gross believes there are attempts to modernise it in other ways, including the question of cost.

He says while it's not uncommon for coronations to happen during economically difficult times - citing George VI's, which was held during a great depression - the decision to reduce the guestlist for King Charles' to a quarter of the numbers that attended his mother's might be an attempt by the palace to keep costs "reasonable".

But at a time when people are struggling financially, critics say a coronation costing millions is a public waste of money. The Department of Culture, Media and Sport wasn't able to provide estimates but clearly it won't be cost-free. Nor could it yet reveal how much the Queen's state funeral cost last year, though for comparison, the Queen Mother's in 2002 reportedly cost £5.4m.

The public reaction to both their deaths, however, suggests there remains some level of interest in the monarchy.

An estimated 250,000 people lined up in September to see the late Queen lying in-state and similar numbers turned out for her mother, external. Relative to the UK population of 67 million this might seem low but about 40% watched the funeral on TV.

Whether the coronation has the same effect remains to be seen, though Prof Whitelock is sceptical.

"There's no doubt some people will watch it and say it's what Britain does best with the pomp and pageantry. But the idea that one man, who by accident of birth, is being anointed and set above the rest of us; who is unelected, and doesn't represent Britain religiously or ethnically, jars badly."

- Published2 May 2023

- Published3 March 2023

- Published1 March 2023

- Published14 February 2023