A Very British Cult: Inside Lighthouse, the life coaching cult that takes over lives

- Published

Jeff Leigh-Jones joined Lighthouse to find direction in life, but the group tried to separate him from his family

Lighthouse promises life coaching to help people realise their dreams. But an 18-month investigation by the BBC finds it takes over people's lives, separates people from their loved ones and harasses its critics.

Jeff Leigh-Jones had only been part of Lighthouse for a few months when his girlfriend Dawn noticed something strange was going on. Jeff no longer seemed himself.

Jeff had joined the pioneering life coaching and mentoring group to help him find more direction. He had been planning a solo hike to the South Pole, and thought a coach could help him get more disciplined.

But then Jeff began spending all day on secretive phone calls and avoiding friends and family - he even sold his house to invest more money in the group.

One day, Dawn overheard one of Jeff's many supposedly motivational daily calls. It wasn't about the South Pole at all - it was about her. Jeff was told he needed to choose between Lighthouse and his family.

In November 2021, Dawn contacted the BBC. "We've had private investigator reports into Lighthouse," she says. But "you can only ever go so far". She was nervous. Lighthouse isn't an ordinary life coaching organisation, Dawn explained. "It's a cult."

Worried about Lighthouse's effect on her boyfriend, Dawn contacted the BBC

Life coaching is a booming UK industry. There are an estimated 80,000 to 100,000 people working in the field.

Unlike many therapists or counsellors, who are trained to help people come to terms with difficult or traumatic pasts, coaches say they focus more on clients' futures. In theory at least, they try to help people work out what they really want and how to get there.

In the past few years, Lighthouse - formally known as Lighthouse International Group and based in the Midlands in England - has received hundreds of thousands of pounds from mentees. It boasts of helping thousands of people.

Set up in 2012 by businessman Paul Waugh, it claims to be different from most life coaching groups.

Its founder, who grew up in South Africa and tells people he was a multimillionaire by the age of 35, says he has developed a revolutionary approach by fixing people's spiritual wellbeing.

When Jeff found the group via an online book club run by a Lighthouse devotee called Jai Singh, he thought it could help him too.

Jeff says he was looking for inspiration from someone successful and Jai - a former property developer in his late 30s with a calm and engaging manner - seemed to be just the man.

"I thought he was smart," recalls Jeff. "He was interested in the same ideas I was interested in."

Pretty soon the pair spoke daily, sometime for hours at a time. Gradually conversation drifted into Jeff's personal life. Relationship troubles. His past. His insecurities. The honesty seemed to help Jeff focus.

"It was brilliant at first," Jeff says of these early sessions. He soon paid £10,000 for a year-long mentoring course to help improve his discipline. "I was motivated. I was inspired."

After several months, Jai Singh offered Jeff the chance to get more involved with Lighthouse. Jeff was delighted, even if it did cost him £25,000.

Jeff hit it off with his Lighthouse mentor Jai Singh, who persuaded him to pay £25,000 for closer involvement with the group

It was a lot of money, but Jai had warned the price would soon go up further if he delayed this decision. And besides, Jeff was told he would make the money back with all the new business opportunities that would surely follow.

"He said it would be the best opportunity for me to succeed," says Jeff.

Jeff became something called a "Lighthouse Associate Elect". It meant he could tap into Lighthouse's network of brilliant entrepreneurs - sitting in on their daily meetings and even training to be a mentor himself.

He would also get guidance from Lighthouse boss Paul Waugh. Jai said Paul counted Bill Gates and Warren Buffett among his contacts.

Jeff handed over the money, and Lighthouse began to take over his life.

Catrin Nye investigates a life coaching company that takes over your life. As the story hots up, they fight back, and there's a surreal final showdown.

Watch now on BBC iPlayer (UK Only)

Every morning at five, Jeff would prepare for a daily call where Lighthouse business would be discussed. Initially it was just a catch-up. But within six months the calls sprawled to five or six hours long with up to 30 people online.

Jeff shut himself in a room deep in concentration, eyes locked on his laptop - following a peculiar ritual of transcribing Paul Waugh's thoughts and ideas.

The schedule, often running from 05:00 to 22:00, was relentless with little time off. But these calls weren't what Jeff had signed up for.

Call transcripts seen by the BBC reveal little of the expected talk of self-help, networking and business success. They recorded something quite different.

Perhaps the most important idea in Lighthouse is something called "the levels". Paul Waugh - borrowing ideas of a famous American psychiatrist called M Scott Peck - says everyone falls into one of four levels of spiritual development.

Level one is a "chaotic, childlike" state - while level four is a conscious and present person, free of constraints and fear.

The key to success, explained Paul in his calls, was to get to level four. Jeff was told he needed weeks of work to get there and achieve his goals. But weeks became months, and months became a year.

Lighthouse founder Paul Waugh expected followers to transcribe his every word on hours-long calls

When Jeff got frustrated on one call, Jai Singh told him to up his efforts and stop being emotionally "lazy".

In fact, only one person in Lighthouse was a level four - and that was Paul Waugh himself.

Everyone else was stuck at level one. And the main reason for that, the Lighthouse founder said, was the negative influences around them. (Paul has since said a handful of other Lighthouse "seniors" have finally reached level four after more than a decade with the group).

Lighthouse also pushes the idea that the greatest obstacle to climbing the levels is often a person's family and friends.

"All families have difficulties and Lighthouse would find them," says Jeff. "Find them in your journal or find them in your personal mentoring."

Families, said Lighthouse to Jeff, were narcissistic and controlling. Including his own. They didn't want to let their loved ones go and they would sabotage mentees' potential, Jeff was told. They were dangerous.

Erin, who became a Lighthouse Associate Elect at the same time as Jeff, tells a similar story. She joined after a divorce, hoping to kick-start a new career - and at first it seemed like a decent way to do it.

"An investment in herself", the group called it. But talk of business opportunities turned into revisiting her difficult past.

Erin, whose name we have changed, told her mentor that when she was about 13 she had been sexually abused by someone known to her family.

Lighthouse wanted her to take her parents to court and "make them pay for not taking better care of her". Erin now believes it was to free up more money, which she could then invest in Lighthouse.

"Why aren't you taking it out on them?" Paul Waugh said on one call to her. "Why aren't you trying to get justice there?"

We've now spoken to 20 people who've left Lighthouse. A similar pattern has emerged. People join a mentoring group, usually looking for a career change or new direction. Things start off well - and happy mentees invest more money.

But before long, it drifts into endless introspection about troubled backgrounds and awkward families - who mentees are encouraged to think of as "toxic" influences to avoid.

Life coaching is not a regulated industry with strict professional codes like psychotherapy. And, while there are qualifications available, anyone can claim to be a life coach - thousands do.

Paul Waugh said: "What qualifies us is experience. Mentoring isn't a qualification, it's an experiential thing."

But coaching in the wrong hands can be dangerous. Before he joined Lighthouse, 30-year-old Anthony Church had struggled with anxiety and depression, suffered a breakdown and attempted suicide.

Early mentoring sessions with Jai Singh seemed to help, and he eventually handed over £5,000 - half his life savings - for more coaching.

After a while, Jai encouraged Anthony to reduce his medication, even coaching him on what to tell his doctors to convince them his mental health had improved.

Lighthouse encouraged Anthony Church to reduce the medication he took for depression and anxiety

Recordings of calls handed to the BBC reveal Jai telling Anthony that medication "is not a long-term solution because it doesn't encourage the person to consciously make decisions to command and reprogramme the subconscious mind".

When a doctor agreed to cut down his dosage, Anthony started complaining of withdrawal symptoms. Jai said it was "part of the process".

Caroline Jesper, head of professional standards at the British Association for Counselling and Psychotherapy, listened to hours of calls between Anthony and Jai and said if any of her members behaved in this way, the association would investigate under its professional conduct procedure.

If you have been affected by Lighthouse you can contact Catrin Nye on Twitter @CatrinNye, external

Those who became part of Lighthouse were told slightly different things about what the money they had paid was for. But they were all told their "investment" bought them pioneering Lighthouse mentoring which would transform their lives.

Often, they were told they would make their money back quickly through networking opportunities, new business ideas or by becoming mentors themselves. They were also told they were helping to fund Lighthouse's charity work in Africa.

Former mentees say they were encouraged to borrow money to pay for courses. Erin says she got a credit card at Jai's suggestion.

To devote himself full-time to Lighthouse, Jeff stopped working and sold his house - ultimately investing £131,000 in the group. But according to the people we spoke to, none of the returns ever materialised.

After two years, doubts started to creep in for Jeff. But he knew Lighthouse could be ruthless with dissenters.

When Anthony began querying whether Lighthouse was helping him, Jai said he was being paranoid as a result of withdrawal symptoms from his medication. When he left and sent other Lighthouse mentees information about cults, Jai threatened to call the police.

And when another former mentee, a teacher in her 50s named Jo, discussed her experience on an online forum, a senior Lighthouse member contacted her school and said she was a danger to children.

When a teacher criticised Lighthouse, a senior member wrote to her school to make accusations against her

Erin, meanwhile, was berated as a "cynical old witch" when she asked where her money had gone. Paul reminded her they had recordings of her disclosures about the abuse she'd suffered as a child.

"I started to become increasingly unwell," says Erin. "I'd even physically throw up."

And when she did eventually leave, Paul made good on his threats in a YouTube video, where he named Erin.

He later edited her name out after being warned that identifying a victim of a sexual offence without their consent was a criminal offence.

The turning point for Jeff was when he took time off to visit his dad in the US. Away from Lighthouse, he began to see things differently.

He recalled playing golf with Paul Waugh and watching a senior mentor scurrying after him carrying his equipment. At one point, the senior mentor dropped to his knees to tie Paul's undone shoelace.

"I thought, is that where I'm going?" says Jeff. "I realised the level of control he had over these people."

When Jeff returned and announced he was quitting, Paul Waugh bombarded him with messages, some friendly, some hostile, to try to get him to stay.

Lighthouse told him to wait two years for any return on his money and warned him that creating controversy could jeopardise his investment.

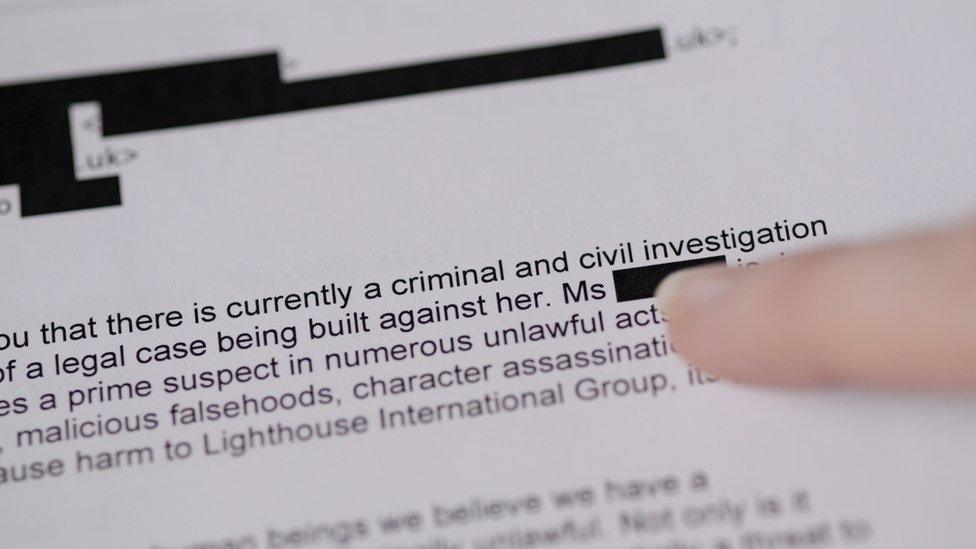

Jeff asked for a refund, and the group responded by saying it would be "stepping up" investigations into Jeff and his girlfriend Dawn.

In the end Lighthouse contacted Dawn's employers and claimed she was a dangerous internet bully.

Attacking critics seems to be part of the group's modus operandi. When we put our allegations to Paul Waugh and Lighthouse, the group claimed data protection rules prevented them from responding properly.

It accused the BBC of being part of a smear campaign, and went on to target online people who it suspected we had interviewed, including Jeff and Dawn.

Seven Lighthouse-related accounts were shut down by Twitter for hateful conduct shortly after we first got in touch with Paul Waugh, including one named "Parents Against Trolls".

More than 40 people who have left Lighthouse, or have loved ones in the group, or have been close to its leader, spoke to the BBC for this story. Many others were too scared to speak.

Yet there are still dozens of people who remain part of Lighthouse today. And for many of them, Paul Waugh's promised high life remains out of reach.

"I was able to walk away, but I don't think a lot of people in there have anything to walk to," says Jeff. "They've committed too much."

One woman who rented a six-bedroom house to Paul Waugh, said she ended up with eight Lighthouse team members living there. The house became "absolutely filthy" and every bedroom had been converted into a bedsit.

For a time, after they all moved out, three or four letters arrived daily about unpaid bills.

Another ex-landlord told us he had received about 150 letters from debt collection agencies addressed to people involved in Lighthouse.

The BBC searched public records and found 17 county court judgements against nine current members of Lighthouse. Jai Singh, Jeff's mentor, had £20,000 worth of unpaid debts. Paul Waugh had no county court judgements against him.

Nearly all those who've been part of Lighthouse have told us they think Lighthouse is a cult. Everyone we spoke to with family members involved in Lighthouse think the same. And Lighthouse is a growing concern to the people who monitor cults too.

We spoke to 10 different cult experts from the UK, US and Canada. Among them are five people with PhDs, two winners of the Margaret Singer Award for cultic studies and three accredited therapists with extensive experience working with ex-cult members.

"There is a cult in your neighbourhood," says Dr Alexandra Stein, a cult expert

Seven of these experts told us they believe Lighthouse is a cult. Two preferred a different terminology - although both said they were concerned about Lighthouse. The final expert said they would rather not comment.

One charity which helps people break free from abusive groups, Catalyst, says it now receives more calls about Lighthouse than any other UK organisation, with "over thirty" people asking for help.

Sitting on day-long mentoring phone calls seems a far cry from the popular image of a cult - where depictions tend to be about mysticism and new religions.

But the experts say cults are opportunistic, latching on to new trends, even if that is self-help for entrepreneurs. They are defined by how they can control members' money, time and even thoughts.

Cult expert and social psychologist Dr Alexandra Stein says: "There's a such a strong stereotype that the only cults are in California where people wear long orange robes. There is a cult in your neighbourhood."

She says for people with loved ones inside a cult, "it's like a living death" - partly because attempts to criticise the group often backfire, leaving them unsure how to act.

Cults want families to get angry and complain, so the family needs to avoid criticism, stay in touch and be available, Stein advises. She accepts it can be extremely challenging.

Karina Deichler, whose brother Kris has been part of Lighthouse for more than a decade, says when they were younger the pair were more like best friends than siblings.

But last year, when Karina wrote about her concerns about Lighthouse online, Kris reported her to the police for being an internet troll. The police took no action.

"It's just crazy," Karina says. "I just feel numb now. I'd so love to have him back".

In February this year, the UK government made an application for the firm behind Lighthouse - Lighthouse International Group Holdings Trading LLP - to be closed down.

After investigating it since June 2022, the business secretary argued the company was working against the public interest.

According to court filings presented by government investigators, Lighthouse was not keeping proper records and was not co-operating with their investigation - which meant it was impossible to determine the "true nature" of the business.

Paul Waugh failed to attend at least five scheduled interviews, and even told investigators he was not going to help them.

It was found that between March 2018 and July 2022 about £1.2m was paid to Paul Waugh himself - roughly half the firm's income. The company also did not appear to pay tax or any ordinary business expenses, such as rent or utilities.

Paul Waugh argues he receives more than half the money because he pays for some of Lighthouse's expenses himself and is the biggest investor in the people at Lighthouse.

On 28 March this year, there was a hearing at the Royal Courts of Justice in London attended by around 20 Lighthouse associates and mentees, including Paul Waugh.

Government investigators told the court that it was "wholly unclear" what Lighthouse actually does. Despite the claims of pioneering research, they could "only identify significant amounts of money passing to Paul Waugh as its prime mover".

Judge Cheryl Jones decided it was in the public interest to close down Lighthouse International Group Holdings Trading LLP.

As he left the courtroom, Paul Waugh told us he had wanted to close Lighthouse down for a while - but that the group would not be stopping its work. It was now going global.

When asked why so many people think his group is a cult, he said: "They don't know what a cult is… they're slurring us, they're smearing us." He added that most of our allegations "were absolute nonsense".

BBC reporter Catrin Nye challenged Paul Waugh outside the Royal Courts of Justice

He later posted online that he was working on a documentary called "A Very British Broadcasting Cult" - knowing our podcast series is titled A Very British Cult - which would investigate "Catrin Nye's sinister cover up attempt".

Lighthouse argues it has helped lots of people overcome obstacles to their potential through mentoring, life-coaching, counselling and community support. It also says people who have given money were investing in themselves and are not entitled to refunds.

Although Lighthouse International Group Holdings is now in receivership, there is little to stop the people behind it carrying on its work.

The group is already evolving. Since it came under scrutiny, it has started to rebrand with a new emphasis on Christianity rather than self-help.

Its website says it now trades as "Lighthouse Global", which promises to share "our 18 year journey from personal development into Christ and the persecution we have suffered along the way".

Jeff doesn't expect those still involved will think any differently after the court case. "They're thinking 'I've got to protect Lighthouse, I've got to protect Paul Waugh.' Logic is gone."

The day after his firm was shut down by a judge, Paul Waugh went on Twitter. "I asked the judge to close our old company down," he wrote, triumphantly.

"It was a master stroke" replied one of his followers.

Reporting team: Osman Iqbal, Ed Main, Jo Adnitt, Aisha Doherty and Thanduxolo Jika.

Contact Catrin Nye on Twitter @CatrinNye, external

Are you affected by issues covered in this story? Share your experiences by emailing haveyoursay@bbc.co.uk, external.

Please include a contact number if you are willing to speak to a BBC journalist. You can also get in touch in the following ways:

WhatsApp: +44 7756 165803

Tweet: @BBC_HaveYourSay, external

Please read our terms & conditions and privacy policy

If you are reading this page and can't see the form you will need to visit the mobile version of the BBC website to submit your question or comment or you can email us at HaveYourSay@bbc.co.uk, external. Please include your name, age and location with any submission.

Related topics

- Published23 November 2021

- Published4 February 2023

- Published27 October 2020

- Published20 August 2019