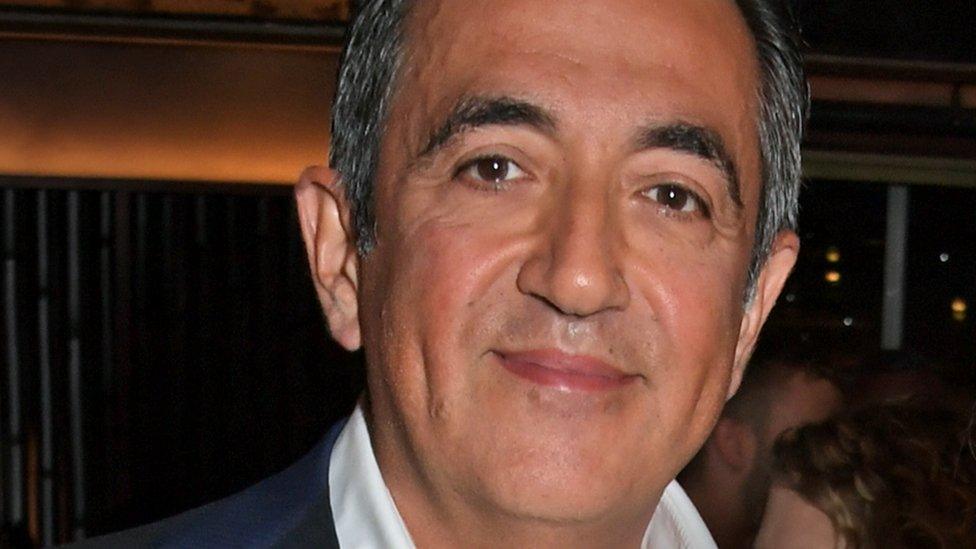

Javad Marandi: Why the BBC battled to name top businessman

- Published

The identification of Javad Marandi came after an enormous legal battle

This week BBC News ran a story that has been 19 months in the making.

We reported that some foreign companies belonging to Javad Marandi, a top British businessman and major donor to the Conservative Party, had featured in a money-laundering investigation.

His identification came after an enormous legal battle, all the way to the doors of the Court of Appeal.

So why did we do it, and why did we win?

The story began in October 2021 when the National Crime Agency (NCA) asked a judge to let it seize millions from the family of one of Mr Marandi's business associates.

Mr Marandi was not the legal target of the NCA's forfeiture case - we should stress that Mr Marandi denies involvement in any wrongdoing and is not subject to any criminal action.

But in the case, the NCA alleged some of his overseas interests had helped move around some of the cash they believed had been syphoned out of Azerbaijan in a global scandal.

The NCA says money trail began with cash moved into bogus firm in Baku, Azerbaijan

On the morning that case began, the court stopped the media from naming Mr Marandi, after his lawyers argued that he would be so damaged from being identified that it would breach his legal right to privacy.

The media had not had, in practical terms, proper notice of this application and despite arguments from two reporters in court, the restriction was imposed - turning Mr Marandi into "MNL".

Fast forward to January 2022. That's when the judge in this case ruled that the NCA could indeed seize more than £5.6m.

His judgment concluded some of Mr Marandi's companies had indeed played a central role in moving the cash - and he agreed to hear the BBC's arguments in favour of lifting the restriction on naming Mr Marandi.

We went back to court and argued that there was no longer any proper justification for the reporting restriction.

And the court agreed, lifting the order.

But that wasn't the end of it. Mr Marandi's lawyers successfully persuaded the High Court to look again at his claim on anonymity. That meant bringing in far more senior judges whose judgment would influence many other cases to come.

And this is where the affair became potentially serious for media freedom.

Privacy laws trumping media freedom

Over the last decade, the courts have been developing interpretations of privacy laws that, it's fair to say, have increasingly alarmed many in the British media.

While Mr Marandi was concerned about his own privacy and reputation, his challenge, if successful, could have had far-reaching implications for the media's ability to report court proceedings.

His lawyers argued he was entitled to anonymity, despite the fact he had featured in a court case in an open public court.

In legal terms, that was a massive attack on the UK's open-justice principle - the public's right to learn what has been said and done in courts.

The BBC argued that the open-justice principle was so well-established, that anyone who wanted to restrict it, where they would normally be named in court, would have to mount incredibly powerful and clearly evidenced arguments.

Mr Marandi had been granted anonymity under a special court order, which is more typically used to protect vulnerable people - such as victims of blackmail.

The law, we argued, was clear: reporters should only be restricted from reporting proceedings for exceptional reasons - and even then, a restriction must be supported by "clear and cogent evidence" and must be strictly necessary.

And in this case, we argued, Mr Marandi had not met these tests.

The High Court agreed, external.

There was one last throw of the dice to the Court of Appeal - but there, Lady Justice Andrews refused to permit the case through the door for a hearing.

"[Mr Marandi] may not have been a party to or a witness in the [NCA's] forfeiture proceedings, but that did not mean that he had no fair opportunity to address the allegations made against him," she wrote in her ruling.

"He could have refuted them in detail when he put in his evidence in support of his claim for anonymity. Instead, he chose to rest on a bare denial of wrongdoing."

And that's why the BBC was able to report a story that we believe was strongly in the public interest to disclose.

Related topics

- Published16 May 2023

- Published31 January 2022