Concrete crisis: Headteachers in weekend dash to make schools safe to open

- Published

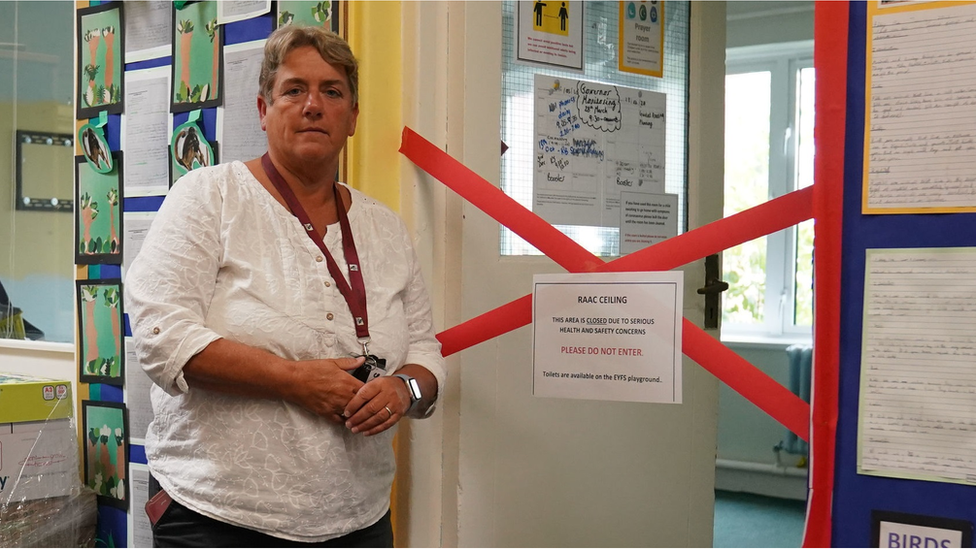

Head teacher Caroline Evans and her staff sit in a temporary staffroom in the corridor of Parks Primary School in Leicester

Headteachers in England are in a race this weekend to find ways to reopen their schools after being told to shut buildings made with unsafe concrete.

Many from the 104 affected schools are busy rejigging timetables, seeking alternative classrooms and trying to rent temporary toilets.

Frustrated parents are being emailed last-minute plans for home learning and moving children to other schools.

The government said affected parents should have been informed by now.

It said it would publish a full list of schools with buildings known to contain reinforced autoclaved aerated concrete (RAAC), but wanted to wait for headteachers to make initial contact.

The Department for Education (DfE) told 104 schools and colleges in England to partially or fully shut buildings at risk and introduce safety measures, just days before the start of a new academic year.

In Scotland, RAAC has been detected in 35 schools but First Minister Humza Yousaf said he has no plans to close any schools at this stage.

The building closures across England are set to have far-reaching consequences for children and their teachers.

Sarah Skinner, who is in charge of three schools in Suffolk and Essex built using the concrete that has been likened to an Aero bar, told the BBC the late notice was "incredibly challenging".

The CEO of Penrose Learning Trust said one school has 12 classrooms out of use, another has 16 classrooms, a gym and toilet closed, and a third has 10 classrooms shut.

"It just seems very late in the day, and that's what's created the problem to now be finding temporary accommodation, temporary toilets, marquees on fields, our kitchens are out action. There are a lot of things beyond finding a classroom we have to consider," she told BBC Radio 4 Today programme.

"We've been on the phone all day to temporary classroom companies... we have a very little playground [in one school] so actually getting 10 classrooms in there is going to be a challenge, and then there's the logistics of getting electricity run to it safely."

A headteacher at a special needs school in Essex has been calling parents individually to break the news.

Louise Robinson, of Kingsdown School, said: "Instead of preparing to welcome our students back to class, we're having to call parents to have very difficult conversations about the fact the school is closed next week.

"We're hoping that a solution can be found that allows us to open the school, at least partially, but that entirely relies on ensuring the safety of our pupils and staff, and approval by DfE."

At one primary school, children will have to be served their school dinners in their classrooms, rather than the dining hall, and at a west London secondary school, students will need to bring in packed lunches while its canteen is out of action.

The DfE said it was grateful to headteachers working at pace to ensure disruption is kept to a minimum and that it expected "rarer cases where remote learning is required" to be "for a matter of days not weeks".

Education Secretary Gillian Keegan would inform Parliament next week "of the plan to keep parents and the public updated on the issue", it added.

Writing in the Sun on Sunday newspaper, external, Ms Keegan said the government had "no choice" but to close schools, and that it was not a decision it had taken lightly.

"I want to reassure families that this is not a return to the dark days of school lockdowns," she said.

Labour will try to force the government to publish a full list of schools which are impacted when the Commons returns from its summer recess on Monday.

The government has said it will release a full list "in due course" but has not provided a timetable. BBC News has been compiling its own list.

The closure of schools at late notice will come as a headache to many parents who will have to take leave from work or arrange childcare for younger school children.

One parent told BBC Essex she could have cried when she was told her child's school would be shut until at least mid-September as temporary classrooms were needed.

"Literally I work Monday to Friday, so to try and find childcare has been a bit of a mission," Hayley, who did not give her surname, said.

"To turn around and say 'Reece, you're not starting school this week' has been quite heart-breaking."

She described the timing of the school closures as "rubbish" considering the issues around RAAC had been previously known.

Watch: How RAAC concrete can crumble under pressure

There were warnings on Saturday this could be just the tip of the iceberg, with concerns about the state of other public buildings like hospitals and courts.

Dame Meg Hillier, chair of the Common's Public Accounts Committee, told BBC Radio 4's PM programme that seven hospitals were "totally built" with aerated concrete and around £1bn was being spent making them safe.

The Labour MP also said she had visited one hospital where heavy patients had to be treated on the ground floor because of the risk of roof failure.

She described the costs of working around the problem using props to support existing structures and surveying RAAC-affected areas as "eye-watering" and harder to absorb for small schools already facing tight budgets.

Teachers' union NASUWT wants ministers to publish the list of affected buildings.

"It could be years before all the schools are rectified. They may be able to put up props, conduct surveys and so on, but those are interim measures," said national negotiating official Wayne Bates.

The government says it has been aware of RAAC in public sector buildings, including schools, since 1994 and has advised schools to have "adequate contingencies" in place since 2018.

However, after a beam, which had been thought to be safe, collapsed last week, the matter of the safety of these buildings was given further attention by the government.

On Thursday, the DfE said any space or area in schools, colleges or nurseries with confirmed RAAC should no longer be open without "mitigations" in place.

Every case of suspected RAAC that has been reported to the DfE has been allocated a surveyor and will be visited "imminently", the BBC has been told.

Schools in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland are also being assessed for the material.

RAAC is a lightweight "bubbly" form of concrete used widely between the 1950s and mid-1990s - usually in the form of panels on flat roofs, as well as occasionally in pitched roofs, floors and walls.

It is less durable than standard concrete and has a limited lifespan of about 30 years.

Additional reporting by Harrison Jones

If your child attends, or you're a teacher at an affected school, you can get in touch by emailing haveyoursay@bbc.co.uk, external.

Please include a contact number if you are willing to speak to a BBC journalist. You can also get in touch in the following ways:

WhatsApp: +44 7756 165803

Tweet: @BBC_HaveYourSay, external

Please read our terms & conditions and privacy policy

If you are reading this page and can't see the form you will need to visit the mobile version of the BBC website to submit your question or comment or you can email us at HaveYourSay@bbc.co.uk, external. Please include your name, age and location with any submission.

Related topics

- Published2 September 2023

- Published13 February 2024

- Published19 September 2023

- Published1 September 2023

- Published1 September 2023