Thousands at risk of poor home care because of low fees

- Published

Thousands of people who need support at home face an increased risk of poor care because of low fees paid by the NHS and councils, care companies say.

Only one UK public authority in 20 pays enough to fund the minimum wage and other staff costs, research suggests.

This means some companies struggle to find enough staff to support people with complex needs, while others face going under.

Council bosses say they "can't perform miracles" on overstretched budgets.

The government says the sector is getting more than £8bn of extra funding over two years.

Social care, which supports people with tasks such as washing, dressing and medication in their own home, is mostly provided by private or not-for-profit companies and funded by public bodies such as local authorities or NHS trusts.

The financial pressure the councils and trusts are under means they are paying companies less than the work actually costs, according to the Homecare Association (HA), which represents UK home care providers.

The funding gap is likely to get worse, as data shared with the BBC by directors of council social care shows that a third of local authorities in England expect to make additional cuts to services in the next few months.

Victoria Pringle, the registered manager at Welcombe Care in Stratford-upon-Avon, says the fees they receive from public bodies are "really poor". She says potential staff are choosing higher-paid employment because of the cost-of-living crisis.

To help balance the books, her company is taking on more private clients who need care, but Ms Pringle says it is becoming harder for companies to stay financially viable.

Victoria Pringle, a manager at a care provider, says potential staff are choosing other careers because of the cost-of-living crisis

The HA calculates that to ensure workers get the minimum wage - plus to cover travel costs, training, administration, regulation and insurance, with about £1 for profit and reinvestment - an hourly rate of £25.95 should be paid to care providers.

To measure how this compares with the reality, it asked all 276 UK councils and NHS bodies how much they paid on average for an hour of social homecare for someone aged 65 or over.

It found:

£21.56 is the average hourly rate paid by public bodies across the UK

£19.01 is the average hourly rate paid in Greater London - the most expensive place to live in the UK

£16.04 is the lowest hourly rate paid, by Ealing Council in London

In its report, it found only 14 out of the 276 bodies paid the companies enough to cover wages plus other business-related costs. And 18 paid fees that did not even meet the direct costs of employing a care worker.

The minimum wage in the UK is £10.42 per hour for people aged over 23. The devolved nations have committed to pay care workers the voluntary "Real Living Wage" of £12 per hour, which means their overall fees should be higher.

HA chief executive Jane Townson told the BBC that councils and NHS bodies were "driving down fee rates; driving down wages [and] driving down quality".

"Quality care, a strong workforce, and sustainable services cannot be delivered on the cheap," she says.

The Association of Directors of Adult Social Services (ADASS) said its latest survey of council care bosses showed "really tough" decisions being made.

It said a third of senior managers had been asked to make £83.7m in cuts in the next few months - in addition to £806m of savings already made this year.

"Social care leaders and their teams are struggling to find savings and meet people's needs at least minimally," said ADASS president, Beverley Tarka. "But they can't perform miracles from already overstretched budgets."

A recent survey suggested that one in 10 local authorities in England feared becoming effectively bankrupt.

Care provider Victoria Pringle says she is "concerned" about the quality of care offered when fees are low, adding it is "really distressing to see how people have been treated".

Ms Pringle said her company recently had to hand over a person's care to an alternative provider that charged the local authority lower fees. She said the new carers had very little understanding of spoken English, so found it very difficult to communicate with the person being cared for.

"They had no understanding of the correct moving and handling techniques or what equipment was needed. And they had no idea on how to administer medication safely," she explains.

Ms Pringle says her company was so worried, it raised the new care arrangement as an issue of safeguarding with the local authority.

The HA is calling for it to become unlawful for public bodies to purchase services at fees that risk employment and care regulations around wages and training not being followed.

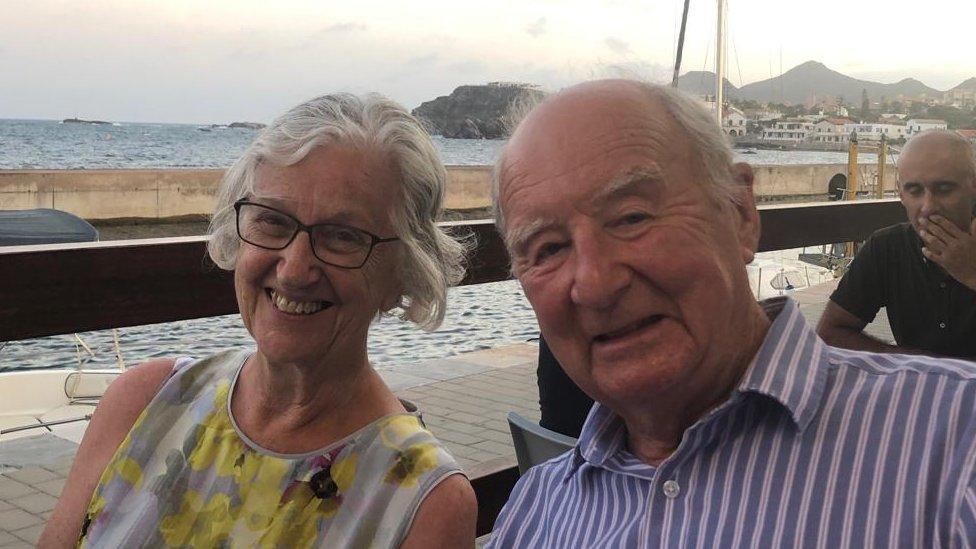

Good support in the home can make a huge difference to families. Anne and Ian are both 82 and have been married for more than 50 years.

Ian says it would be a "tragedy" for him if Anne, his wife of 50 years, was forced into a care home because of a lack of support at home

Anne spent her working life helping others as a nurse, midwife and teacher, but now has severe dementia. Ian does what he can with the help of his son, Craig, who lives two hours away. But they say the support they get from Welcombe has been vital.

"I can't get here very quickly," Craig says. "I can see the attention and care these people offer Mum and Dad, and so it's a huge source of support and reassurance."

Anne's needs are very high, so her care is funded by the NHS. The family say it is regularly being reviewed by the health service, and they worry if funding changes then Anne might be forced into a care home.

"It would be a disaster. I couldn't bear it, it would be a tragedy," Ian says. "I do everything within my capabilities to keep her here."

Since successive governments have delayed reforming the way adult social care is funded, the sector's difficulties are deep-rooted.

Ian and his son Craig say home care is a vital source of support for Anne

ADASS said an additional £900m was needed now to stabilise adult social care in England. It also called for a fully-funded plan in the longer term, which took into account the true cost of social care.

The HA estimates just to pay homecare workers a fair wage, an additional £2.08bn would need to be invested annually in the UK's care sector.

Improving pay is seen as essential if staff shortages are to be tackled. There are currently more than 150,000 vacancies in social care in England alone, according to Skills for Care, the body that monitors the workforce.

Overseas recruitment has eased some of the most acute staffing pressures, but there is increasing concern about the exploitation of some new arrivals.

A spokesperson for the Department for Health and Social Care said it was providing up to £8.1bn of additional funding over two years to support home care, "putting it on a stronger footing for the future and addressing workforce pressures".

The department said it was also reforming the workforce, with a plan to "boost progression opportunities, and encourage take-up of professional qualifications along with learning and development".

Have you left your job in care because of low pay? Has your discharge from hospital been affected by a care package? Has your care been affected by the issues raised in this story? Share your experiences by emailing haveyoursay@bbc.co.uk, external.

Please include a contact number if you are willing to speak to a BBC journalist. You can also get in touch in the following ways:

WhatsApp: +44 7756 165803

Tweet: @BBC_HaveYourSay, external

Please read our terms & conditions and privacy policy

If you are reading this page and can't see the form you will need to visit the mobile version of the BBC website to submit your question or comment or you can email us at HaveYourSay@bbc.co.uk, external. Please include your name, age and location with any submission.

________________________________________

- Published1 November 2023

- Published23 October 2023

- Published20 October 2023

- Published20 December 2022