What is the legacy of the 2001 foot-and-mouth outbreak?

- Published

Foot-and-mouth disease swept though the UK after it was confirmed at an abattoir in Essex in February 2001.

In Britain's first major outbreak of foot-and-mouth for 30 years, nearly 6.5 million sheep, cattle and pigs were slaughtered to control the disease and photos of burning pyres of animal carcasses shocked the country.

But what was the legacy of the crisis?

The farmer

Trevor Wilson, a farmer from Cark in Cartmel, Cumbria, watched the foot-and-mouth crisis unfold with horror.

And in May 2001 he noticed that several of his sheep looked ill.

"They were just lethargic and lying under the fence," he said. "When you looked inside their mouths there were lesions on their tongues."

He said the disease was never confirmed but his flock of 420 sheep had to be slaughtered because of suspicions they had contracted it.

"It was such a shock at first," he said. "You do the best you can to nurture livestock because that is your livelihood and what you have always known.

"So to see everything you've done and worked for destroyed is terrible."

He said the flock included lambs which were only a few days old, while most of the sheep were only 12 months old.

Mr Wilson's farm then covered 25 different sites and so he had about 3,100 sheep and 200 dairy cows which were unaffected.

He said the restrictions were also very difficult and made it a "terrible time" for farmers.

Many sheep and lambs died because they could not be brought inside and it made the lambing season particularly fraught, he added.

"There's nothing worse for a farmer than thinking a lamb is going to die of hypothermia and not being able to save it," he said.

He said farmers had to accept much lower prices for livestock from slaughter houses because they were unable to transport animals to markets and abattoirs.

Mr Wilson said there had been a lot of changes in British farming over the past 10 years.

But he said a marked fall in livestock numbers was the result of reduced profitability in the industry rather than the foot-and-mouth outbreak.

"I think farms adapted very quickly after the outbreak, but it shocked many farmers and quite a lot moved out of the industry," he said.

"A lot of farmers in Cumbria have diversified to help their business.

"They have gone into all sorts of areas. Some have gone into property and some have bought ice-cream vans."

Mr Wilson used compensation from the loss of his sheep to buy property which he now lets out as shops and homes.

He said farming had seen "10 years of recession" and was facing a real crisis because of increased exports from abroad and falling profitability.

He added with pressures to increase food production by 40% across the world to cope with the growing population, the government needed to seriously consider the way forward.

The animal welfare campaigner

Peter Stevenson, chief policy advisor for Compassion in World Farming, was working for the charity during the foot-and-mouth outbreak in 2001.

Peter Stevenson does not think animal welfare has improved

"I remember that period very vividly - it was horrific," he said.

Compassion was against the government policy which at one time recommended slaughtering livestock within 3km (1.9 miles) of infected farms.

"There was no discretion involved," he said. "It was that policy and its inflexibility which led to such large numbers of animals being slaughtered."

He said the charity argued there was insufficient scientific evidence for the policy and some scientists said in many cases the disease did not spread beyond a few hundred metres.

Mr Stevenson said the speed at which the animals were slaughtered and the fact it had to happen on farms raised concerns among animal welfare charities.

"There were many accounts of slaughters being carried out inhumanely, involving immense suffering to animals," he said.

He said ministers had been slow to bring in restrictions on moving animals and "inflexible" over the issue of vaccination, which Compassion believed was an "important part of the solution".

Mr Stevenson believes lessons have since been learnt.

"The public was distraught at seeing such large numbers of healthy animals being slaughtered and I don't think that could happen again," he said.

Mr Stevenson believes the foot-and-mouth outbreak in Surrey four years ago was better handled with animal movements immediately restricted.

Economic demands

He said the charity did not link foot-and-mouth to "factory" farming, but had hoped the 2001 outbreak would lead to other methods.

"At the time we hoped the shock of foot-and-mouth would cause a rethink about the way we farm animals and as a society we would move away from the industrial approach to farming.

"But sadly that hasn't happened," he said.

He said most pigs and poultry in the UK and the rest of Europe were intensively farmed and this resulted in animals suffering.

"Other serious diseases can develop and spread in the highly overcrowded conditions of factory farming," he added.

"Although the foot-and-mouth crisis led to a rethink about how diseases should be tackled and a similar disaster avoided, I think as a society we have not improved animal welfare as a whole."

Mr Stevenson added that increasingly dairy cows were being intensively farmed as a result of economic demands.

"If people want to still see dairy cows out in the fields they have to be prepared to pay a little more for milk," he said.

Government chief vet and Defra

The outbreak of foot-and-mouth disease in 2001 was handled by the then Labour government, which delayed an election because of the crisis.

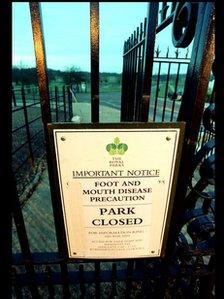

Many farms and parks were closed to stop the spread of the disease

The Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food (MAFF) was replaced by the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra) within months of the crisis unfolding.

Nigel Gibbens, the current government's chief veterinary officer, said: "Foot-and-mouth was a devastating blow for British farmers and the country in 2001, and this anniversary is upsetting for many who lived through it.

"We have learnt many lessons on how to prevent and manage exotic animal disease outbreaks since then and we work closely with farmers and vets whose experience and knowledge is invaluable."

The government said the focus was on prevention and it provided a lot of information about the disease and encouraged farmers to report anything suspicious early.

Mr Gibbens added: "We are not complacent. We monitor disease outbreaks around the world assessing the risk, and regularly update and test our contingency plans, and policies for dealing with them."

Defra said many measures had been introduced, such as stricter hygiene rules for the transportation of animals and improved checks to find smuggled animal products.

A Defra spokesman said: "In any outbreak we would be prepared to vaccinate from the very start and contracts are in place to quickly mobilise this."

However, he stressed there were "crucial factors" to consider such as whether it was known where the outbreak had started.

He added that vaccination in the event of an outbreak would mean the UK would not regain disease-free status for at least three months - costing the farming industry "tens of millions of pounds".