Life at the coal face: Who are the UK's 21st Century miners?

- Published

Hatfield Colliery is one of the country's 12 remaining deep coal mines

The UK's biggest mining firm UK Coal has been fined a total of £450,000 for safety failings which led to the deaths of four men underground. It follows the deaths of a further five men at collieries this summer. With the dangers of the industry back in the news, who are the country's remaining miners and why do they do it?

"You get filthy and my nails have never been any good but I absolutely love being a miner."

Stuart Foweather started at Cadeby Colliery in Doncaster in 1978 as a 16-year-old apprentice.

Now aged 49, he is a mechanical engineer employed by UK Coal, which operates a handful of the country's remaining 12 deep coal mines.

Mr Foweather is typical of many of today's working miners.

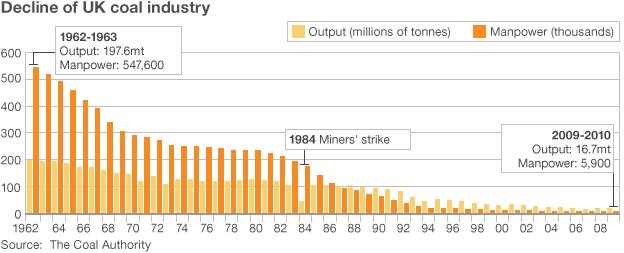

They are men who started when coal production was booming and are now highly skilled in a specific industry which has rapidly declined over the decades.

Explosive gases

Looking back to when he first started, Mr Foweather said: "Coal mining then was very labour intensive. It was tough, hard work, with five to six hours of your shift spent shovelling.

"I remember I got paid £27.10 a week. You went from being a lad at school to a young adult. That's just how it was in those days."

Advances in technology have rapidly modernised the mining industry, with machinery reducing the need for hard, physical labour.

But it does not eliminate the reality of dangerous work in dark, dirty, noisy chambers filled with explosive gases some 1,000 metres below the surface.

UK Coal was fined after admitting offences under health and safety law in relation to the deaths of four men in 2006 and 2007.

Trevor Steeples, Paul Hunt and Anthony Garrigan died in separate accidents at the Daw Mill colliery, near Coventry, in 2006 and 2007.

Nick Gawthorpe is one of about 500 people employed at Maltby colliery

Paul Milner died after being fatally injured at the now-closed Welbeck colliery, in Nottinghamshire, in 2007.

More recently the mining industry has claimed the lives of an additional five men.

Philip Hill, 44, Charles Breslin, 62, David Powell, 50 and Garry Jenkins, 39, died when Gleision Colliery in the Swansea Valley flooded on 15 September.

That was followed by the death of Gerry Gibson after a roof fall at Kellingley Colliery, North Yorkshire, on 28 September.

At the industry's height in the 1920s, 1.2m men were employed in the pits and approximately 2,000 died in accidents every year.

Today there are only about 3,500 miners but each time there is a death it is national news.

Figures from the Health and Safety Executive (HSE) show that in the decade ending March 2011, there were 17 fatal injuries in the mining industry in Britain.

Many of today's miners appear unfazed by the risks, the dangers offset by an opportunity to take home a good wage.

Pay varies depending on the job underground.

Covered in dust

Working on the coal face - considered the best paid job in the pit - can earn a miner about £40,000 a year.

Throw in bonuses and overtime and that earning potential rises to £50,000.

Other jobs below the surface such as a beltman (the person who maintains the conveyor belt used to transport material) or a loco man (the miner who operates the locomotive) are less well paid, averaging about £16,000.

At Maltby colliery in South Yorkshire, men return from their day shift underground covered head to toe in coal dust, dark rings under their eyes like heavy eye make-up.

Steve Mace, a coal face worker and National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) official at Maltby, said: "It's a hard job but I love it.

"The camaraderie is totally different to any industry because of the environment we work in.

"Everyone is in it together and we all watch each other's backs."

'Very lucky'

He added: "Mining is a highly skilled industry. You don't just get taken on and start down a mine straight away.

"The men we have here have a wealth of knowledge and experience and that's invaluable."

About 1.2m men were employed in the pits at the industry's height in the 1920s

Many of Maltby's men are proud generational miners who have spent most of their working life below the surface.

Some talk of being "lucky enough" to be given the opportunity of pit work and how they wanted to follow in their father's footsteps.

Mr Mace, 44, started at the colliery as an apprentice when he was 21.

"My dad worked driving the shafts and my uncle worked in the pits too," he said.

"I was very lucky to get the opportunity and it was my family that got me into it.

"In those days the younger lads got trained by the older miners and you were watched like a hawk.

"If you did anything wrong you got a clip around the ear."

The pit's history in Maltby dates back to 1907 when work on sinking the original shafts began, turning the area into a typical mining town.

The colliery company at the time built an estate of 1,000 houses for its workforce.

Kevin Barron, the MP for Rother Valley, worked at Maltby for more than 20 years, following both his grandfathers, father and older brother into the profession.

"I enjoyed being a miner and that was because of the camaraderie you had," he said.

"Given the environment you worked in if you didn't laugh you would have cried."

He added: "I used to think the job could be bad at times but compared to the conditions my father worked in it was nothing.

"I used to remember him going down the pit wearing just his helmet, boots and lamp. It was too hot for clothes."

Although the town is no longer home to the colliery's workers, efforts have been made to keep the spirit of generational mining alive at the pit with a recent scheme which has seen the sons of current miners being given jobs.

Seventy new men have been recruited to facilitate a new shift pattern at the colliery and 15 of those have joined their fathers who already work there.

Working on the coal face is the best paid job underground

Mr Mace said: "There was so much competition as we had more than 500 people apply for the 70 vacancies."

Nick Gawthorpe, 28, started at the colliery in February, joining his 54-year-old father Mick.

"My granddad and uncle worked in the pits and I always wanted to go down," he said.

"Before this I was a self-employed gas fitter but things had got pretty bad and I was going under."

He added: "This has given me job security. It's meant me and my fiancée have been able to buy a house and we're now expecting our first baby."

For today's miners, the dangers of working in such a high-risk industry seem less of a problem for them than the public perceive.

Mr Foweather said: "Mining is now virtually as safe as it can be. Every effort is seriously made to make it as safe as possible."

Ryan Gamble, command supervisor at Maltby, said: "Of course you've got to watch what you're doing but accidents happen when you do something wrong, it's as simple as that."

- Published18 October 2011

- Published17 October 2011

- Published15 October 2011

- Published14 October 2011

- Published12 October 2011

- Published4 October 2011

- Published30 September 2011

- Published28 September 2011