Then and now: The Mines Rescue Service

- Published

The Mines Rescue Service is on call around the clock to help at any of the UK's six remaining coal mines

In August 1993, a section of roof collapsed over an underground roadway at Bilsthorpe Colliery in Nottinghamshire.

Three miners were rescued but another three men were killed. The Mines Rescue Service was called to recover the bodies - with the last one retrieved 64 hours after the accident happened.

Among the rescuers was Andrew Watson, then 37.

"When I got to Bilsthorpe, 16 hours after the collapse, we were getting changed to go underground and we had people on the surface just crying at us."

According to Mr Watson, the service "does not have a great history in saving people's lives".

"In the majority [of cases] it's about getting in to recover bodies," he said.

So, what motivates someone to do such a traumatic job? And in more than 100 years since its creation, how has the Mines Rescue Service changed?

Between 1870 and 1880 about 2,700 men and boys were killed in the UK's mines.

In response to the loss of life, a Royal Commission was set up to improve safety standards, but it was not until the Coal Mines Act of 1911 that Mines Rescue Centres became required by law.

'Organised chaos'

By 1918, 43 stations were established, but now - because of the decline of the UK's coal industry - only six remain.

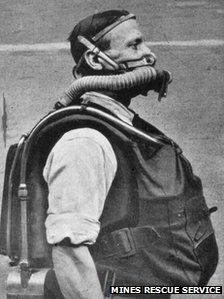

The equipment has changed significantly over the past 100 years

Stuart Richardson, 46, is an officer with the rescue service at its headquarters in Mansfield Woodhouse, Nottinghamshire.

In 2011, he led a team into Gleision Colliery in Swansea, where four miners had lost their lives.

While he is not allowed to go into much detail about what he saw, because an investigation is continuing, he describes such situations as "organised chaos".

And he said the hardest part of the job was seeing the families of the miners who are in trouble.

"It's something we have to deal with ourselves," he said.

"If we need counselling it's available but the camaraderie we have here... we've all been through similar situations and we can offload things on to each other.

"You don't ever want to be used [in a rescue]," he said. "Because if I'm doing this somebody is in trouble."

Underneath the Mansfield Woodhouse base are training galleries designed to test the skills of the brigadesmen, and to recreate the possible conditions of a mine emergency.

The rooms can be filled with smoke, the temperature can be raised and the layout altered to replicate conditions in a real mine.

Mr Richardson, who qualified in 1991, said: "We train the lads to be the best they can to prevent loss of life."

The base's core team is on call 24 hours a day, seven days a week, and miners from collieries across the country also visit the site to be trained in rescue methods.

But since the 1990s, when it was privatised, the service has had to fund itself.

'Moving into prevention'

It receives 15% of its income from the coal industry, but otherwise relies on contracts from blue-chip companies like Coca Cola to help train staff working in factories with confined spaces.

Mr Watson, who is now the service's commercial manager, said the business makes about £5m a year.

"We don't have a big problem generating income," he said.

"At the end of the day we don't make a profit, we just want to generate enough income for ourselves to make sure the equipment is kept as modern as it can be."

But as the UK becomes less dependent on coal, what does the future hold for the Mines Rescue Service?

"It's moving into prevention," said Mr Watson. "We're making sure standards are kept as high as they possibly can, people won't call us out then."

But should that ever happen, where would it leave Mines Rescue?

"That's a risk we'll have to take," he said.

- Published29 February 2012

- Published18 September 2011

- Published16 September 2011

- Published15 September 2011