Protected food names: Quality or cartel?

- Published

There is a multi-billion Euro market for products which have got into the Protected Food Name club - but not everyone can join

What's in a name? Well, if it's the name of a tasty local food, then legal wrangles, multimillion-pound sales and the threat of small local traders going to the wall.

Those bidding to gain legal protection for the Lincolnshire sausage are licking their wounds after their latest attempt was rejected by the government.

And while they may cast envious glances towards the likes of Melton Mowbray pork pies, external and Stilton cheese, external, even these established names face challenges.

The argument focuses on the European Union's Protected Food Names , external(PFN) scheme.

Like a trademark, PFN gives products which meet certain standards protection from unauthorised imitation.

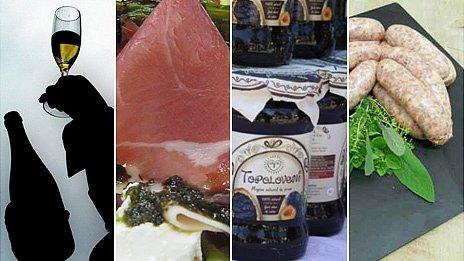

It includes food celebrities like Champagne and Parma Ham along with more niche treats like Magiun de Topoloveni (a Romanian plum-based fruit spread), but also covers produce like vegetables and wool.

Food minnow

For those who get it, PFN status means guaranteed standards, enhanced profile and the chance to get a premium price.

But for those on the outside, it is restrictive, counterproductive and open to abuse.

The UK is a relative minnow in the PFN stakes. According to the EU DOOR database, external (which combines some similar items), of the 1,130 registered products, 44 are from the UK - compared to Italy's 247 and France's 192.

Nonetheless, the UK market is estimated to be worth more than £1bn.

And it's a slice of that the Lincolnshire Sausage Association , externalwas after.

Reputation 'ruined'

Its chair, Jane Godfrey, believes they represent everything PFN stands for.

"The Lincolnshire sausage is a distinctive name that should represent a quality product, clearly connected to a specific area," she said.

"But anyone can make a Lincolnshire sausage, pretty much anywhere, with any ingredients they like - and that's ruining its reputation.

"We wanted to make sure it was made the right way in the right place and in the process protect about 160 traditional butchers in the county."

Not all pork pies are equal, only those with the right meat, pastry, shape and origin are Melton Mowbray

In the UK, a producer must get approval from Defra before it is rubber stamped by the EU.

The government department ruled that, despite the name, an "enduring link" between the county and the product had not been proven - but Mrs Godfrey also points the finger elsewhere.

"The difference between our application and others was the financial muscle set against us.

"An objection came from a solicitor representing, among others, Walkers Midshire Foods which is owned by Samworth Brothers, who don't want to have restrictions on where and how they make Lincolnshire sausages."

Market leader

Samworth Brothers is a Leicestershire-based food company which had annual sales of more than £700m in 2011.

They also own Dickinson and Morris, a major player in the £50m Melton Mowbray pork pie market, a product which was granted a PGI in 2009.

In addition, they own Ginsters, a leading maker of Cornish pasties, which gained PGI status in 2011.

A spokesman for the company said: "We have invested in Leicestershire and Cornwall specifically because they are both areas of great food heritage and food provenance is important to us.

"PGI status promotes the integrity of a regional food product and protects it from misuse and imitation.

"It helps ensure product consistency and quality for the consumer, and means that producers can make long term investments with confidence.

"Each PGI status application has to be judged on its own particular merits. There must be a unique and intimate connection between the product and the designated locality."

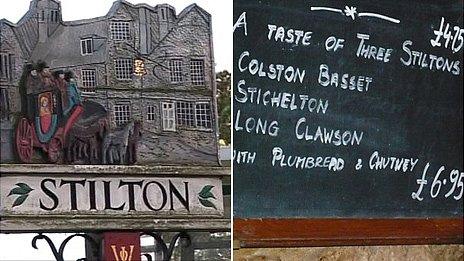

Stilton cheese gained its PDO - the highest level of protection - in the first wave of applications in 1996

Defra has confirmed that in the past two years, only one other product - Jersey butter - has had a bid for protected status rejected.

Stilton Cheese gained its PDO in the first wave of protected names in 1996. It accounts for 50% of the blue cheese market and it is worth more than £60m.

Only five dairies, in Derbyshire, Nottinghamshire and Leicestershire, are licensed to produce Blue Stilton - but that exclusivity is under fire.

Name game

With some irony, the village of Stilton in Cambridgeshire - acknowledged source of the name - is outside the approved area.

An ongoing campaign to gain the name for their own blue cheese has provoked threats of court action.

Separately, a Nottinghamshire dairy has appealed to Defra to broaden the criteria on what can be called Stilton.

Stichelton cheese is made in the right area, to the right recipe but crucially uses unpasteurised milk, in breach of the PDO criteria.

Stilton's exclusivity is being challenged by the village after which it is named and a nearby artisan diary

Stichelton dairy owner Joe Schneider said: "For me the importance of the PFN is to concentrate on those narrow parameters of tradition, linked to a geographical area.

"I'm afraid it gets hijacked sometimes as more of a branding and marketing exercise and it becomes protectionist instead of inclusive.

"The system is good in theory but it needs better policing to make sure it is not misused."

'Zero' recognition

But Matthew Rippon, a food researcher at Queen Mary, University of London, warned against seeing PFN as the preserve of small producers.

"Traditional is not the absolute opposite of commercial," he said.

"There's no reason why a cottage industry can't be protected and there's no reason why a massive manufacturer can't be protected, as long as they can prove to the regulating body that they have the appropriate link with the place for a certain period of time.

"It can be as big as Parma ham or small as Staffordshire cheese.

"The main problem for the system is that public recognition of it is about zero. Food has a lot of labels and information on it already and people just don't look for the (PFN) symbol.

"Plus there is a lot of scepticism about EU schemes, which makes it a difficult sell, even though this one is protecting the very Britishness of a product.

"The only thing that is going to change that is big publicity, which is the preserve of government or large firms."

- Published29 October 2012

- Published22 October 2012

- Published18 October 2012

- Published27 September 2012

- Published20 April 2012

- Published3 January 2012