Fracking confusion: How UK has been 'fracked' for decades

- Published

Campaigners protested in Parliament Square, London, in December

Protests by environmental campaigners have increased awareness of hydraulic fracturing, or "fracking", but the process has been used in the UK's oil and gas industries for decades.

So what has changed, and why are people worried about fracking now?

In West Sussex, environmental activists hold up pun-laden signs near the entrance of the Cuadrilla site in Balcombe.

"Get the frack off our land," reads one, while another claims "Fracking kills: Don't bore Balcombe to death".

But 160 miles (260km) north, in the Nottinghamshire village of Beckingham, 71-year-old John Foster walks his dog next to fields which have been fracked for oil and gas for decades.

"I've been here since 1969 and at one time there were nodding donkeys [machines used to lift oil out of a well] dotted all over the place," he said.

But he and his neighbours agree the oil and gas extraction has not affected them.

Cuadrilla is drilling an exploratory oil well in Balcombe and does not have consent to frack for shale gas

The remaining nodding donkeys - which are used after the fracking process - are difficult to spot in the landscape.

The occasional passing tanker is one of the few clues that oil is being extracted from under the ground.

Next to the fields is Beckingham Marshes, a wet grassland habitat managed by the RSPB.

The charity has objected to fracking for shale gas in Lancashire and West Sussex but has not objected to fracking at Beckingham Marshes.

Why not?

"It's a bit of a misnomer," said Michael Copleston, site manager at Beckingham Marshes.

"Shale fracking and fracking are two different things.

"It's silly in a way to get drawn into a debate about shale fracking when shale fracking doesn't occur at Beckingham Marshes."

But this has not stopped people worrying.

Some contacted the RSPB with concerns after a newspaper compared the fracking around Beckingham and Gainsborough, external with that being protested against in Balcombe.

Andrew Austin, chief executive of IGas Energy, the company running the site, said fracking is "standard oilfield practice".

"Clearly, the world has not ended in Beckingham," he added.

So if fracking for oil and gas has not caused the world to end in Beckingham, why are people concerned about fracking for shale gas in the rest of the UK?

There has been no fracking for shale gas in or near Beckingham Marshes

Prof Richard Davies, from Durham Energy Institute, at Durham University, said people are concerned the UK could become like the US, where there is widespread fracking for shale gas.

"What's going on in America is on a completely different scale to what has been done historically; 25,000 wells are being drilled in America every year to be fracked," he said.

"Old fracking was done on a small scale in the UK but in America the scale has been ramped up. If you scale up a process, the chances that there is a problem goes up."

In comparison to the US, there are 2,152 inland wells in the UK.

According to the Department of Energy and Climate Change, about 200 of these have been fracked.

Nodding donkeys, such as these in Beckingham, are used to extract oil after the fracking process

"My response to the industry that says we've already been doing it [fracking] is 'That is absolutely correct'," said Prof Davies.

"Fracking used to be used to crack the rock to keep production going and it has been at a small scale.

"But what we are looking at is a dramatic expansion in the amount of drilling and fracking in the UK."

So when a protester is described as being "anti-fracking", a less banner-friendly description could be "opposed to widespread hydraulic fracturing for the extraction of shale gas".

Fracking for shale gas would not have been economically viable in the past, but changes in technology have made it more cost effective.

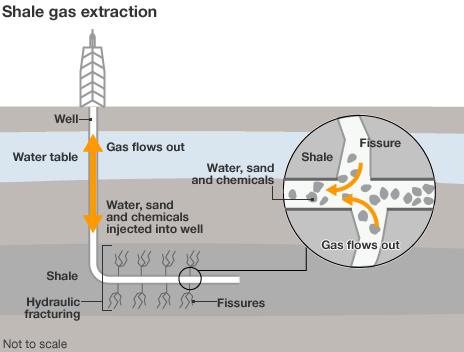

A significant development has been horizontal drilling.

"If you are drilling horizontally you are able to access a larger area," said Kevin Taylor, professor of petroleum geology at the University of Manchester.

The chemicals used have also changed.

Prof Davies said: "There has been an evolution in fracking technology; nitroglycerin in the 1950s, gels in the 1980s and slick water in the 2000s.

"You are pumping a fluid underground at sufficient pressure to crack rock.

"All of those processes are fracking, but the technology has evolved."

The Department of Energy and Climate Change (DECC) stressed that Cuadrilla does not have consent to frack for shale gas in Balcombe, and the public would be consulted before permission could be given.

"At the moment Cuadrilla are drilling an exploratory oil well in Balcombe," said a DECC spokesperson.

"Public consultation is intrinsic to the process for securing planning permission, which is required for each stage of exploration, appraisal and production."

- Published21 August 2013

- Published19 August 2013

- Published17 August 2013

- Published1 December 2012

- Published1 December 2012

- Published10 November 2012

- Published6 August 2011

- Published28 May 2011

- Published24 May 2011