World War One: The tank's secret Lincoln origins

- Published

Traditional infantry attacks could not break defences of trenches, barbed wire and machine guns

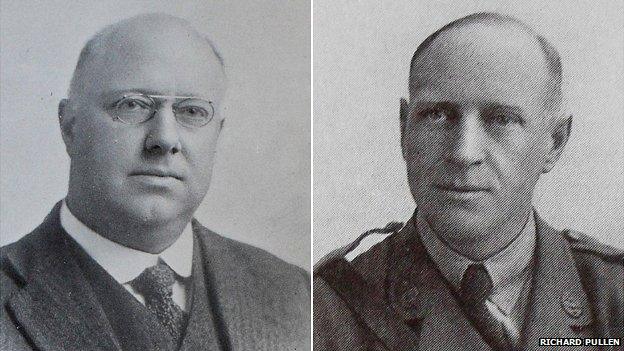

William Tritton and Lieutenant Walter Wilson both had experience of working with engines - and the army

Tritton, Wilson and draughtsman William Rigby would burn failed sketches on the fire of the hotel room

.jpg)

The first design - christened Little Willie - failed to cope with test trenches but a new concept was waiting

The Mark I tank was unlike anything seen on the battlefield before and bewildered friend and foe alike

"The panic started, everyone from 1st and 3rd Companies jumped out of the trench and ran the fastest race of his life, pursued by the merciless tank machine-gun fire which cut down many men as if it were a rabbit-shoot."

So remembered German soldier Wilhelm Speck, of the 84th Reserve Regiment.

Some ran. Some stood and fought. But no-one forgot their first meeting with a tank. A weapon without precedent, which went on to dominate the battlefields of the 20th Century.

And it was designed by two men, in little more than two months, working out of a small hotel room in Lincoln.

Science fiction

"By 1915, the British army knew it had an immense problem," said David Willey, curator at the Bovington Tank Museum, external.

"Instead of a war of movement, the battlefield had become one of defensive trenches protected by thickets of barbed wire and machine guns.

"So how to get through that? How do you break in to the German trenches?

"To their credit, senior officers recognised technology might offer an answer. This brought a lot of crackpot ideas out of the woodwork but also some with more potential."

Armoured cars had been around for years, but with standard road wheels they were almost as helpless as cavalry when faced with ditches and dugouts.

Vast ironclad war machines were the stuff of science fiction. It needed a harder head to find a solution.

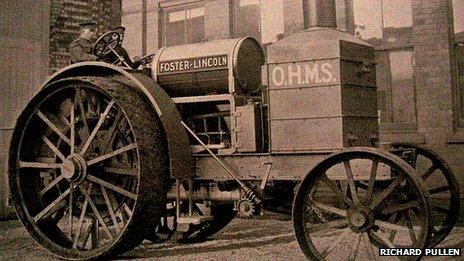

Fosters had already made giant artillery-towing tractors for the army

Winston Churchill, then First Lord of the Admiralty, had listened to the swirl of bold ideas and nagged cabinet colleagues for action.

In February 1915, the Admiralty Landships Committee began to examine ideas. But where to test them out?

The choice seems, at first, rather odd.

William Foster and Co Ltd, in Lincoln, specialised in threshing machines.

But historian Richard Pullen explains the logic.

"Foster's had worked with powerful - and tracked - machines for farms," he says.

"This translated into making tractors to tow big artillery guns in the early days of the war.

"So, the army knew they had experience, knew they could deliver and Lincoln was a nice, quiet spot away from prying eyes."

The work needed more than technical experience, it needed two very particular men - William Tritton and Lieutenant Walter Wilson.

"Tritton was a brilliant engineer," says Mr Pullen. "And he was a brilliant leader. He got things done.

"He turned Foster's around with new ideas and new markets.

"Couple him with Walter Wilson, who was also a good engineer but a genius with things like gearboxes, and they made a brilliant partnership."

On 22 July 1915, a commission was placed to design a machine that could cross a trench 4ft (1.2m) wide.

To get away from the noise and distraction of Foster's factory, a suite was taken at the White Hart Hotel, in Lincoln.

Secrecy surrounded the project with early models reportedly being painted with Cyrillic letters to back up disinformation they were snow ploughs for Russia

"They locked themselves in the room and would scribble designs on envelopes and cigarette packets," says Mr Pullen.

"Anything they liked went to the factory for testing, anything they didn't went on the fire."

They knew they had to work fast.

"Everyone was worried the Germans would come up with a similar machine first," he explains. "It could change the course of the war.

"It was also viewed as a way to save the lives of men on the front by breaking the deadlock. Every day longer it took meant more British soldiers died."

A first design, little more than an armoured box on US tractor tracks, known as Little Willie, was tested on 19 September.

It failed.

Picnic panic

A 5ft (1.5m) bank could not be overcome and as it crossed a trench, the tracks sagged from their rollers and came off.

Officials from London, who only dared whisper about the project, were dumbfounded to find workers had invited their families, complete with picnics, to the tests.

"When challenged," said Mr Pullen, "Tritton growled that to treat the whole thing as a big secret would attract more attention."

Tritton had spotted the problem early and new tracks were being designed from scratch. Bigger, tougher and built to cling to their frames.

Fitted with the new system, Little Willie could cross the 4ft gap. But, the challenge had changed. The army now faced trenches 8ft (2.4m) wide.

However, Wilson had also been looking ahead and had the answer ready.

Instead of being tucked at the bottom of the machine, the tracks would go all the way round its 25ft 5in (7.75 m) length. They would also be carried on forward-sloping "prows" projecting beyond the crew compartment, giving it a huge reach.

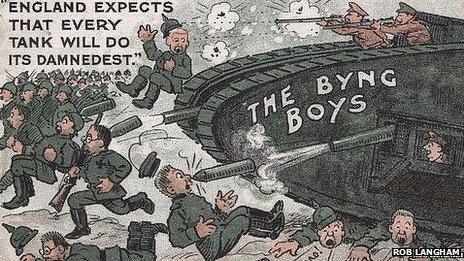

The idea of tanks electrified a public concerned the war had become a hopeless stalemate and German's lead in technical innovation

The famous "wonky box" lozenge shape was born.

Variously known as Centipede, Mother and Big Willie, it would weigh 28 tonnes.

"It was a design ahead of its time," said Mr Pullen. "It pushed technology to the limit and beyond.

"The engine they had to use was not really powerful enough - steering, command and tactics were in their infancy. But, the need was desperate"

Make or break

In line with the break-neck speed of the project, the design was approved at the end of September, a prototype was ready in December.

After encouraging tests in Lincoln, the machine was taken to Hatfield in Hertfordshire, to be run across a mock battlefield for an audience of senior politicians and soldiers.

The newly codenamed Tank (a deliberately vague term inspired by its boxy shape) bellowed into life and crashed over ditches, crossed a bog and crushed wire barriers.

Its creators waited for the official verdict.

Fosters set up a production line to cope with a huge demand for the new weapons

One officer called it a "slug" and pronounced it too heavy for French bridges. Lord Kitchener, the Minister of War, felt it was "a toy" and "without serious military value".

General Butler, representing Commander in Chief Douglas Haig and the most important opinion in the audience, leant over to a colleague and said: "How soon can we have them?"

Mr Willey said: "The direct military impact of the tank can be debated but its effect on the Germans was immense, it caused bewilderment, terror and concern in equal measure.

"It was also a huge boost to the civilians at home. After facing the Zeppelins, at last Britain had a wonder weapon. Tanks were taken on tours and treated almost like film stars.

"And the example of the tank gives the lie to the myth that World War One generals were backward and dullards.

"Here they looked for a new weapon, approved its use, then trained up the men to use it, all within a year."

Hear how the development of the tank was kept top secret and find out more from Peter Barton about the battles fought underground at the Western Front.

The story of Lincoln and the birthplace of the tank will also be broadcast on BBC Radio Lincolnshire at 08:15 GMT on Wednesday 26 February, as part of World War One At Home.

- Published20 December 2013

- Published5 July 2013