World War One: Tungsten 'the armour plate of conflict'

- Published

Carrock mine produced vital tungsten but was in the hands of Germany until the eve of the war

It was the new miracle metal. It more than doubled the efficiency of steel armour. It did the same for artillery shells, along with the barrels that fired them and the tools which made them.

In 1912, with war clouds gathering, tungsten was key.

Fortunately England had a mine devoted to producing high quality tungsten ore. Unfortunately it was owned by Germans.

"Tungsten is an extraordinary metal", said Dr John Emsley, a fellow of the Royal Society of Chemistry and author of Nature's Building Blocks. "It's almost as hard as a diamond and has one of the highest melting points of any mineral.

"Adding a small amount to steel makes it far harder, far more resistant to stress and heat. The benefits to industry are obvious"

For the British, the great arms race of the early 20th Century was in ships, dreadnoughts bristling with 12in (305mm) guns and wreathed in 14in (350mm) thick steel plate.

'Regarded as impurity'

For Belgium and France, eyeing the growing tension in continental Europe, immense investment went into vast steel and concrete fortresses, like those at Liege and Verdun.

Something which could crack concrete and smash armour - or conversely blunt a shell - might just swing the outcome of a war.

Dr Emsley said: "While tungsten steel's amazing properties were discovered by an Englishman, Robert Forester Mushet, in 1864, British industry never truly mastered its refinement.

"Tungsten had been found in the mines of Devon and Cornwall for years but it was generally regarded as a impurity in the production of tin.

"The real centre for producing tungsten steel was Germany.

"At the beginning of the 20th Century, for most people, tungsten was something used in those clever new lightbulb things. Only Germany thought of it as a strategic metal."

Germany industry was a world leader at producing tungsten steel and using it to build bigger and more durable weapons, especially artillery

This lukewarm attitude to the metal meant Carrock mine in Cumbria, the only site in England devoted solely to wolframite, the main tungsten ore, had struggled to be profitable.

But with an eye to the future, the German-owned Cumbrian Mining Company took it over in 1904.

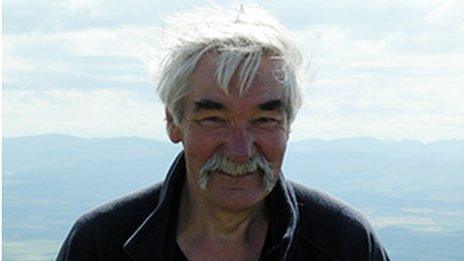

Mine historian Ian Tyler said: "They knew exactly what they could do with it. If you sprinkled just a bit into molten iron and stirred it up, you get tungsten carbide.

"This is high-grade performance steel, armour plate, cutting tools - a very rare composite and a very rare process.

"It was so valuable that when they found some gold in this mine, they didn't even bother with it."

"And [the British] hadn't twigged this. [The Germans] were digging it out under our noses."

Mr Tyler added: "Sometimes I make the glib remark that nearly all our tungsten mined up to 1912, we got back on the Somme."

Allied blockade

Such was the their domination of the trade that shortly before war broke out, British industry was getting 90% of its tungsten via German companies.

It could not be tolerated. As hostilities moved closer and the importance of tungsten became clearer to the British authorities, the Cumbrian Mining Company went into "liquidation".

It was smartly replaced by the government-backed Carrock Mining Syndicate. A state-of-the-art processing facility was installed and production increased.

But the Kaiser's army already had substantial quantities of wolframite and tungsten-hardened steel.

Dr Emsley said: "Artillery dominated the war from the start, with massive guns firing 1,800 lb shells reducing forts to rubble. But it was not just about the size of the guns but how long they could be used.

"German armament makers perfected some that could fire up to 15,000 rounds without becoming unserviceable, compared to Russian and French weapons that became unserviceable after firing about half this number."

But despite their stockpiles, the vast appetite of the war, combined with the allied blockade, led to shortages of the vital metal.

"The need was so great, tungsten was so important, that the big companies returned to the medieval tin mines of Germany," said Mr Emsley.

"They mined the slag heaps, remembering tungsten was an impurity which their ancestors had worked hard to get rid of."

Between armour and guns, hardened steel was vital for dominating the battlefield

The allies caught on and caught up. A second tungsten mine was opened at Castle-an-Dinas in Cornwall. Larger reserves were found across the world.

During the course of WW1, 14,000 tons of ore were mined at Carrock, producing about 200 tonnes of tungsten.

By 1918, the UK was producing about 20,000 tonnes of hardened steel which required 3,000 tonnes of metallic tungsten.

'Deserve remembrance'

Over four years of bloody fighting dominated by artillery, the German army, and Germany's will to fight, was ground down.

With the end of war, the price of tungsten fell and mining at Carrock ended. Surges in demand during World War Two and the Korean War, briefly led to it being reopened.

But, following the abandonment of the lease in 1988, the mill and associated buildings were cleared completely.

The only remains of buildings left on the site are those on the south side of Grainsgill Beck, the concrete bases of hoppers constructed in 1913 by the Carrock Mining Syndicate.

Mr Tyler said: "Men worked hard to get the ore out of the ground. They did their bit, they deserve to be remembered."

Track Barnes Wallis' role in developing the airships that challenged the German Zeppelins, and explore whether the trauma of WW1 lead to greater creativity.

- Published13 December 2013

- Published5 July 2013

- Published17 August 2012

- Published16 February 2012