World War One: Royal Arsenal's battle to feed the guns

- Published

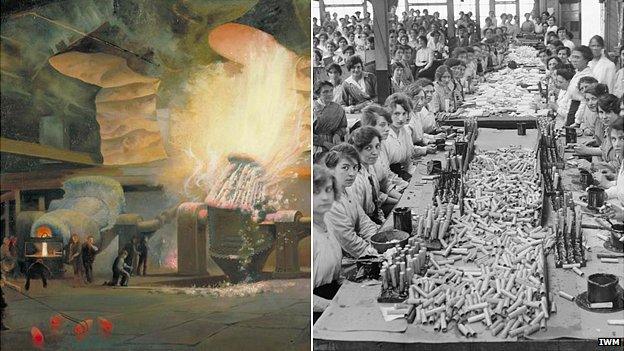

Big and small: The Arsenal made weapons and munitions of all sizes from naval guns to pistol bullets

It was a factory like no other in World War One. The Royal Arsenal was spread across a swathe of south-east London, and it was devoted to the delivery of death.

The Woolwich-based factory was at its peak during WW1, covering 1,285 acres, filled with dozens of buildings and employing about 80,000 people.

It was the focus for some of the seismic shifts the war prompted, from how war was fought to how Britain was run.

"The Arsenal was fundamental to the war," says Paul Evans, from The Royal Artillery Museum.

"Artillery dominated the battlefield and the Arsenal was at the head of everything to do with artillery.

"It was everything. It was research, it was manufacturing, it was testing, it was inspection. You lose the Arsenal, you lose the war."

From a patch of open ground used to test 17th Century guns, the Arsenal was already a sprawling complex at the start of the 20th Century, with more than 10,000 workers.

Buildings like the Royal Brass Foundry, Great Pile, Laboratory and Grand Store hint at its history and scale. It even had its own steel foundry and railway.

By the early 1900s though, it was a hotchpotch of semi-independent departments that had defied attempts at modernisation. But change was coming.

As an English Heritage study of the site put it: "When war did break out in 1914, the Arsenal was congested, inefficient and no longer innovative.

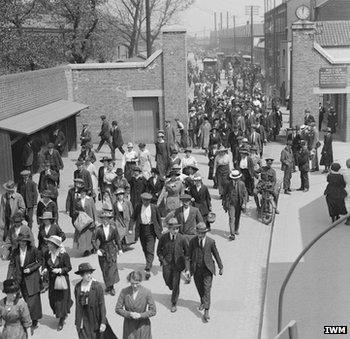

Crowds outside and chimneys within hint at the scale of the Arsenal's work

The war quickly developed into a scramble for bigger and more numerous guns

"Yet, at huge cost, it was mobilized, and feminized, into exceptional productivity."

The unexpected appearance of trench warfare meant Britain's carefully prepared stock of shrapnel artillery shells - designed to be used against armies in the open - was next to useless.

As battles became immense slugging matches between ever larger guns - 366,000 fired in four days by the British at Loos in September 1915, for example - the army ran low on its main weapon, high explosive shells.

And of those arriving at the front, up to 30% proved to be duds.

Long hours

Mr Evans says: "It was nobody's fault, it was just the way the war worked.

Tens of thousands worked in the complex each day

"If you take all of your skilled labour out of the factories and turn them into soldiers, you quadruple the demand for what they are making anyway, and with the people you have brought in you are trying to cut corners anyway to keep up with the pace, it's not going to work."

David Lloyd George, the Minister of Munitions from May 1915, made two big changes.

He increased government control over weapons production - then largely in private hands - and sought to bring women into the workplace.

Nowhere was this felt more than in Woolwich, where eventually almost 30,000 women were employed.

Caroline Rennles was already a "canary" - turned temporarily yellow by working with TNT explosive - when she went to make bullets at the Arsenal.

Interviewed in 1975, she described the unforgiving conditions.

"We would work 13 days out of 14," she said.

"You would work 13 days 7am until 7 pm, have a day off that's all, then do 7pm until 7am.

"On the night shift, the place would be lit with little lamps and you had just enough light to see what you were doing."

'Scandalous' deal

The working week was set at a then-low mark of 48 hours but the legal maximum was 65 for women, 96 for men.

But the arrival of women was neither wholly welcomed nor the end of old prejudices.

Professor of History at Birkbeck College, Joanna Bourke, said trade unions and employers struck hard deals to let the changes happen.

"It's actually scandalous what they do," she said. "They say 'OK we will have women in the munitions factories but we will not have them on the same conditions as men.

"'We will firstly give them duration [of the war]-only contracts and secondly we will divide up the tasks'.

"So instead of having one woman doing the job that one skilled man would have done, they divide it up and have several women supervised by a man.

"This means the women don't have to be paid as much but it also means that at the end of the war the trade unions can say 'They aren't doing skilled jobs, kick them out and give the jobs back to our members'."

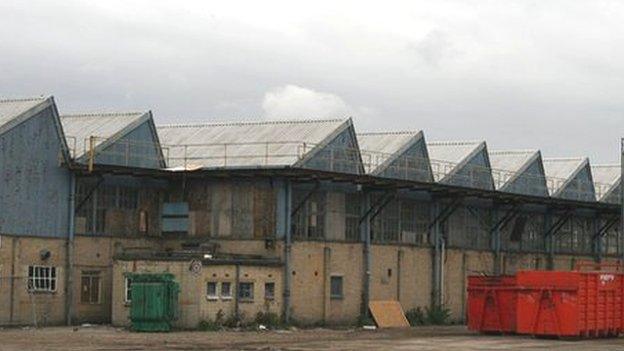

Large parts of the Arsenal complex were demolished in the decades after WWII

First used in the Arsenal's small arms factory, women soon moved into heavy work, such as heavy arms, trucking, crane-driving and "danger work" - handling high explosives.

Changes were not confined to women - in 1914, the site's research department's Explosives Section had only 11 chemists. By 1918 it had 107.

So great was the shift in number and nature of the workforce that nearly 3,000 new homes had to be built on the Well Hall Road and a 700-place creche - believed to be the country's first in the workplace - was set up.

Despite inexperienced workers dealing with munitions, there were no large accidents at the Arsenal - but the explosion at the nearby Silvertown munitions works, which killed 73 in January 1917, underlined the dangers.

While areas have been redeveloped, many traces of the Arsenal's history remain

The shells began to flow. And how.

Mr Evans gives some examples of the numbers: "Expenditure of ammunition in France; 6in howitzer shells, 22,387,363; 18 pounder ammunition, 99,897,670 rounds fired at the Germans.

"Altogether, 170 million rounds were dropped on the Germans. And that is just on the Western Front and that doesn't include bullets.

"There were lots of big guns, firing lots of shells. It explains those photographs of blasted landscapes."

But victory, when it came, was bittersweet.

Female workers began to be laid off even before the war ended but all staff suffered. The Royal Arsenal was regarded as crowded, out of date and dangerous in such a built up area.

By 1922, the workforce had fallen to just 6,000. Bit by bit areas and buildings were sold off, converted or demolished.

The Royal Regiment of Artillery was last to leave, in 1998.

Large areas have now been redeveloped as housing but a link is maintained as Firepower, the Royal Artillery Museum, also occupies part of the site.

Discover the WW1 stars of women's football and let Kate Adie explain what WW1 really did for women.

- Published16 February 2012