How do you fill in a sinkhole and can they be prevented?

- Published

The Peak District hole has now been fenced off and is in the process of being filled in

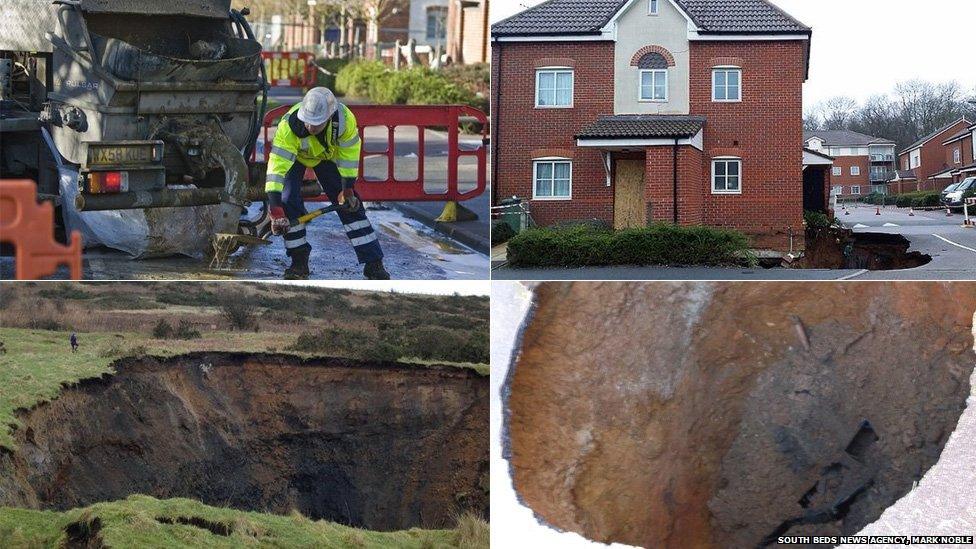

Recently there has been a glut of stories about sinkholes appearing across parts of the UK, including one of the biggest ever seen in the Peak District. But once the ground opens up, how do you fill in a massive hole?

In December, following a spell of heavy rain, a hole measuring about 160ft (49m) wide and 130ft (40m) deep, appeared overnight near the Derbyshire village of Foolow.

While in February, a house in Hemel Hempstead, built on the site of an old brickworks, was left teetering on the edge of a 35ft (9m) wide and 20ft (6m) deep hole, with its occupants forced to evacuate their home.

In Walter's Ash, High Wycombe, a large sinkhole swallowed a family car parked on the driveway.

And most recently, a sinkhole opened up in a residential road in Greater Manchester and a forklift truck collapsed into a suspected sinkhole on Mistley Quay in Essex.

The common theme connecting many of the recent cases is past mining.

Since Roman times, copper, lead, and other materials have been extracted from beneath the British countryside, leaving myriad tunnels and voids.

The British Geological Survey said there are thousands of mine shafts sunk in the Peak Park alone, leaving the land prone to subsidence and although sinkholes open up for all kinds of reasons, by far the most common cause is a sudden influx of water.

Caver Mark Noble, 58, from Eyam, said he came across the Peak District hole during a walk on Christmas Day.

He said he has explored the caves at Foolow in the past where huge cavities were left in the area from an old lead mine.

A mix of concrete can be used to repair most sinkholes, providing the surrounding area is stabilised

Paul Beetham, a lecturer in civil engineering and specialist in geotechnics at Nottingham Trent University, said: "If you go for a walk in the Peak District you will almost certainly be passing over one of many thousands of natural and man-made voids that range from the size of a golf ball to the size of a house.

"Most of the time these voids pose no danger to humans, as there is usually a good depth of solid rock between them and the surface."

However, he said: "While these features may remain intact for hundreds of years, very rarely the sudden collapse of the material, perhaps disturbed by extreme rainfall or a recent change in land use, may occur."

Mining, leaking pipes, burst water mains, irrigation or even emptying a swimming pool can trigger a sinkhole - with some areas of the country being more susceptible than others, depending on the type of rock involved - gypsum is especially vulnerable to rapidly water erosion with the area around Ripon being particularly at risk.

Dr Tony Cooper, of the British Geological Survey, said: "If you took a chunk of gypsum the size of a van and left it in a river it would be dissolved in about 18 months."

Although the causes are the same, the appearance of sinkholes in more densely populated areas can be more difficult to deal with.

Dr Clive Edmunds, part of a specialist team which filled the hole in Hemel Hempstead, said: "Basically, these buildings can be left sitting on fresh air."

So, faced with a gaping chasm in the middle of a housing estate, or a giant hole in the countryside, what can be done to make it safe?

Mr Beetham said the solution "usually depends on the risk the sinkhole poses to humans, property or business".

He said: "If the area is remote then the risks are probably low and the urgency less. However, if the area is accessible to the public then priority would be for a specialist to establish how far the void could open up and ensure the area is made safe."

He added: "If the sinkhole has loose sides, access by heavy machinery could also trigger a wider collapse. In built-up areas, where access is difficult, it is common to backfill by pumping grout [mix of sand and cement] from the surface.

"If there is space to do so, more likely in rural areas, it may be possible to excavate down and cap off the void with reinforced concrete and then compact the overlying fill," he said.

A vast network of caves and old mines runs beneath large areas of the Peak District

The Hemel Hempstead hole, which opened up on top of a former brickyard, took about 200 cubic metres or 17 lorry loads of cement, to fill.

When it comes to identifying possible sinkhole sites, Mr Beetham said: "It may be that they are more likely in regions where properties/developments are older and less robust approaches to development were followed.

"Another issue is that not all mining activities were officially recorded."

He said modern methods should help to mitigate the risk.

Developers conduct searches and use geological maps to look for evidence of known subsidence, or historical mining, he added.

However, Peter Styles, a specialist in geophysics - and part of a team which conducts tests on land where holes have appeared, said: "We are often asked to come in too late - something becomes unstable and you get one cavity - then people say to us 'are there any others?'

"It's quite clear that there are problems we need to look at in a more proactive manner - we need to take notice and start to inspect these sites before we give permission for huge housing developments or infrastructure.

"That is the only way we will actually make things safe."

The Coal Authority takes responsibility for dealing with old coal mines across the country, but there is no national system in place for more than 100,000 redundant non-coal mines to be inspected.

So, more teetering houses, swallowed cars and shifting landscapes remain a possibility - particularly during periods of heavy rain.

- Published29 April 2014

- Published23 April 2014

- Published23 February 2014

- Published21 February 2014

- Published19 February 2014

- Published18 February 2014

- Published2 February 2014

- Published30 December 2013