Looking for life on planets outside our solar system

- Published

- comments

Dr Don Pollacco who is leading the Plato Science Consortium, said it might sound like Star Trek, but finding habitable planets is "real" possibility.

The University of Warwick is taking the scientific lead in a mission to build a one billion euro planet-hunting, space telescope.

It's an extremely exciting project and you can read more about it here.

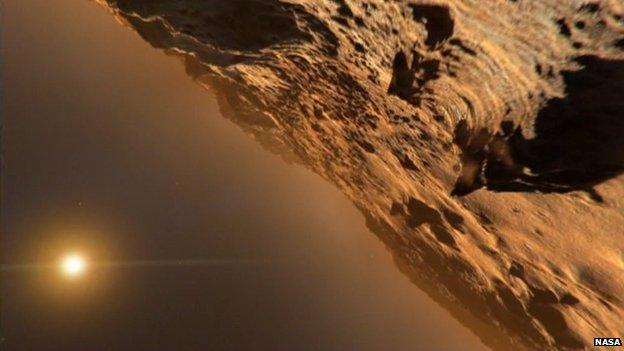

Not so long ago, the idea of being able to detect planets orbiting the stars we see in the night sky would have been firmly considered science fiction.

But then came an extraordinary breakthrough, scientists realised they were able to watch stars and observe the tiny dips in brightness as orbiting planets passed in front of them.

Then came NASA's Kepler, external space telescope. Kepler has used this technique to discover 961 planets along with thousands of possible planets.

Exciting new possibilities

However, despite its amazing achievements, it does have its limitations not least because it is now broken , externaland unlikely to continue planet hunting in the same way.

But even before this sad turn of events, it's worth saying Kepler could only scan a small section of the sky and could only look at quite dim stars.

The new Warwick-led mission called Plato will overcome these limitations by being able to scan huge chunks of sky and look at brighter stars.

This opens up some very exciting new possibilities in our search for these planets.

Plato will be able to identify planets where life is possible - those in the "habitable zone" of a star's system where we could expect to find liquid water on the surface of a planet.

Plato is a chance to learn much more about candidate planets and the stars they orbit

It will then be possible to look at these candidate planets and learn much more about them, including their mass and even the composition of their atmosphere.

For most of us, this is the exciting part of the Plato mission. Analysing the atmosphere means we could see evidence for gases like oxygen and that's a very good indicator of life.

Hard graft

It might even be possible to look for signs of atmospheric pollution which would suggest an industrial society.

But for scientists, Plato is a chance to learn much more about these planets and the stars they orbit.

Detecting signs of alien life is a very distant thought at the moment, but then, as I said at the start, it wasn't so long ago that the idea of finding these planets at all was something out of science fiction.

However, all of this is a long way off.

The launch is set for 2024 so now it's the hard graft of workshops, planning and building to prepare.

After its launch, Plato could gather data for years or even decades -providing nothing breaks as happened with Kepler.

For the young scientists I spoke to working on Plato right now, it could represent years of their future careers and it is hard to imagine a more exciting project in modern astronomy - all led by a Midlands university.

- Published14 March 2014