World War One: How the German Zeppelin wrought terror

- Published

For hundreds of years the Royal Navy had protected the British against attack from the sea, but they were powerless against the new threat from the air

Before the 20th Century, civilians in Britain were largely unaffected by war, but this was to change on 19 January 1915 with the first air attacks of World War One by the German Zeppelin. Historian and aerial specialist Ben Robinson has traced the attacks for Inside Out East.

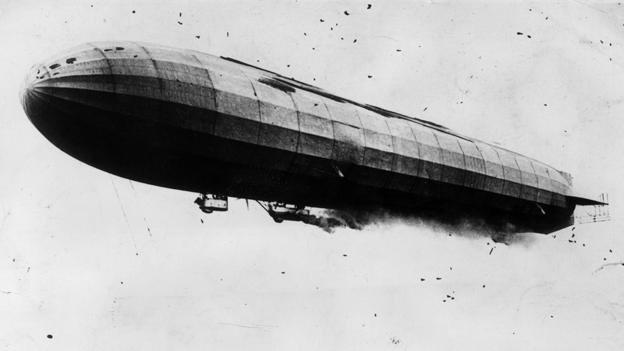

The creation of Count von Zeppelin, a retired German army officer, the flying weapon was lighter than air, filled with hydrogen, and held together by a steel framework.

When the war started in 1914, the German armed forces had several Zeppelins, each capable of travelling at about 85mph and carrying up to two tonnes of bombs.

With military deadlock on the Western Front, the Germans decided to use them against towns and cities in Britain.

The first raid took place on the eastern coastal towns of Great Yarmouth and King's Lynn, on 19 January 1915.

'No military advantage'

Residents reported hearing an eerie throbbing sound above them, followed shortly afterwards by the sound of explosions in the streets.

The full horror of aerial warfare was unleashed. When the smoke cleared, Britain's first ever air-raid causalities were revealed - 72-year-old Martha Taylor and shoemaker Samuel Smith.

Kate Argyle, from English Heritage, said: "There was no military advantage. It was all about instilling terror and really that's what these aerial bombardments did.

"The Zeppelins would come out of the dark - you couldn't see them and it was totally random. You didn't know if you were running towards danger or away from it."

The aim of the Zeppelins was clear - the Germans hoped to break morale at home and force the British government into abandoning the war in the trenches.

In Great Yarmouth, the St Peter's Plain area was worst affected

But there was not the sort of chaos and panic that the Germans had wanted.

"The people reacted very stoically, they got on with the job of clearing up - that British sense of not being fazed by this," Ms Argyle said.

As the people of Great Yarmouth counted their dead and injured, a second Zeppelin was already bombing King's Lynn.

Propaganda value

A further two people were killed, but once again there were no scenes of panic.

Despite this, the propaganda value of the bombings was enormous. Now Britons were not only dying on the battlefields of Flanders but also in their beds at home.

For the next couple of months Zeppelins would hit towns across the east - Southend, Ipswich and Bury St Edmunds were all attacked and six more people were killed.

This house in Stoke Newington was the first ever in London to be attacked from the air

But the Germans were still no nearer to breaking the British spirit, so they aimed for the capital.

A house in Stoke Newington was the first ever in London to be attacked from the air, hit by an incendiary bomb.

Albert Lovell, who owned the house, dragged his family out before alerting the fire brigade.

Aviation historian Ian Castle said: "There had been no raids before, there's never been anything like this. Suddenly a blazing bomb is coming out of the sky and setting light to a house, it's almost science fiction."

The first death happened in Cooper Road at the house of a man called Samuel Legget who had five children. Three-year-old, Elsie, died on her bed.

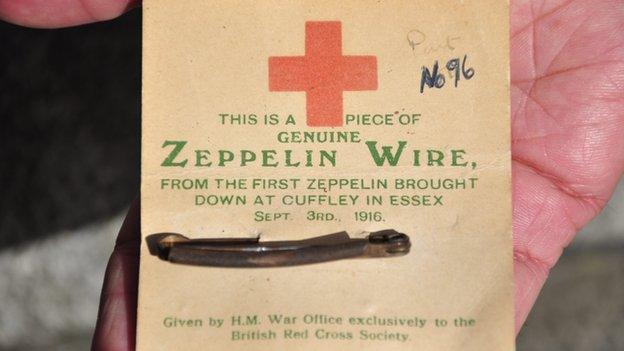

When shot down the canvas of the Zeppelin was burned off and just left piece of relics

In 20 minutes a Zeppelin had dropped 3,000 pounds of bombs, 91 incendiaries that had started 40 fires, gutted buildings and left seven people dead. Not a single shot was fired in retaliation.

From that day forward the Zeppelins were known as the "baby killers".

One person who remembers the attacks vividly is 102-year-old Doris Cobban from Bedfordshire.

She was only five-years-old and living in Lewisham when London came under attack.

"I remember my father coming up to the bedroom and he picked me up and wrapped me in a blanket and he said 'this is history, you must see this'," she said.

The airships were more than twice as long as a modern day Jumbo Jet and thousands of people took to the streets to see them.

Doris Cobban said that for many people the Zeppelins were an incredible spectacle

"My mother took my elder sister who was two years older than I was by the hand and we went out into the road and he [her father] said 'look up there' and over London I saw this long thing and it looked like a huge cigar to me," Mrs Cobban said.

"We were all out there - as far as I remember it was cheerful, but probably the grown-ups were absolutely petrified."

On 8 September, Germany's most successful Zeppelin commander, Kapitanleutnant Heinrich Mathy was to lead the most destructive attack of the war.

Zeppelin shot down

London was ablaze, buildings were ripped apart and by the time the attack was over 22 people were dead, 87 had received horrific injuries and the Zeppelin had escaped into the night completely unharmed.

Gradually better defences were brought in to defend the skies, but it was another year before the tide began to turn.

At the beginning of September 1916 more than a dozen German airships headed for Britain in their largest raid.

Bombs fell in Nottinghamshire, Lincolnshire and Kent but only one airship made it through to London.

It immediately came under heavy anti-aircraft fire and was shot down by 19-year-old William Leefe Robinson.

Some metal was recovered from where a Zeppelin was brought down

While Britain celebrated, the Germans stepped things up with the so-called Super Zeppelins, but Britain had found the Zeppelin's Achilles heel - explosive bullets which could set the hydrogen alight.

This would prove to be the Zeppelin's undoing.

During their brief, but deadly dominance the airships killed more than 500 people and injured more than a thousand in places all down the east of the country.

The last ever attempt to bomb Britain by a Zeppelin was over the Norfolk coast on 5 August 1918.

Three years earlier, when a Zeppelin first appeared in the skies above Great Yarmouth, it was an invincible force, but now they were outclassed and dealt with swiftly.

But the Zeppelin exposed those at home who were now as vulnerable as those on the front line. The government became acutely aware they needed an aerial defence system that operated in depth.

It led to the formation of the RAF in 1918 and to the development of operations rooms such as the one at Duxford that proved so crucial in 1940 during the Battle of Britain and ultimately victory in World War Two.

Follow the route of WW1's most destructive Zeppelin attack and hear accounts of terrifying raids from across the UK.

- Published12 May 2014

- Published1 March 2014

- Published28 February 2014

- Published24 February 2014

- Published22 February 2014