Do cash rewards actually help catch criminals?

- Published

Crimestoppers say that less than 2% of people eligible for a reward actually claim one

Graphic pictures of horrifying injuries and interviews with inconsolable relatives are tactics police use to pull at the heart strings and attract witnesses. But, when it comes down to it, does cold hard cash prove just as effective?

"For anybody that has got that information it might just be the trigger or tipping point for them to come forward," says Nick Howe, a former chief superintendent with Staffordshire Police and now a criminologist at the University of Derby

And yet, the fact is, where rewards are on offer, very few people ever claim them.

Crimestoppers - which takes statements anonymously - offers rewards of up to £1,000 for information that helps the police to make an arrest and charge.

But it says fewer than 2% of people eligible actually claim a reward.

However, the police and newspapers, as well as other private companies, frequently offer large sums of money for information.

So what is the point of offering rewards?

The reason behind putting up the sum of money is straightforward - to create greater media opportunities to glean vital information and help solve crimes.

In cases funded by the police - and therefore the taxpayer - cash rewards are more likely to be offered for "heinous types of crime", Mr Howe said.

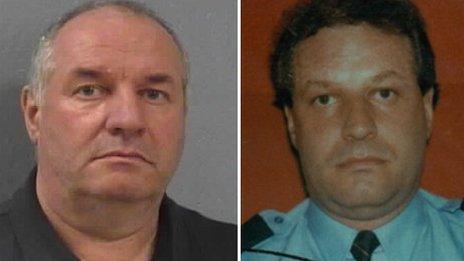

Eddie Maher, pictured on the right in 1993 and on left after his arrest, was jailed for five years in March 2013

"Police rewards are offered in those [cases] which cause moral outrage, so you're talking at the high end of the continuum, things like murder, elderly people that have been severely battered - the ones that appeal to human sympathy and emotion."

However, there is little evidence of whether cash rewards do have a positive effect and how often they are paid out.

Even if the police receive a tip off, it may not amount to anything and conditions on the reward may mean the tipster is not eligible for the money, if the information does not "directly" lead to a successful conviction.

"This can be immensely difficult [to prove]," Mr Howe said.

"In some cases, it is obvious if it is the only piece of evidence standing.

"But in most cases, most evidence, there is a degree of subjectivity and professionalism that has to come in, that puts an indicator to what extent that piece of evidence assisted other evidence to come together."

A case in point is the conviction of Eddie Maher, who was jailed last year for robbing a security van in 1993 in Felixstowe, Suffolk.

After committing the robbery, he fled to the US. Security firm G4S offered a £100,000 reward for information but his former daughter-in-law Jessica King, who told the police where he was, says she has still not been paid one year after he was jailed.

G4S said that while Maher had been found, the sum of money he stole had not, and this "was the basis on which the reward was offered".

Yet, some may argue that offering a reward on the basis the £1.2m is found, is a pretty tall order, and if it had not been Ms King turning him in for the reward, Maher would still be on the run.

Suffolk's Police and Crime Commissioner, Tim Passmore, said there could only be "very few occasions" when offering a reward was appropriate.

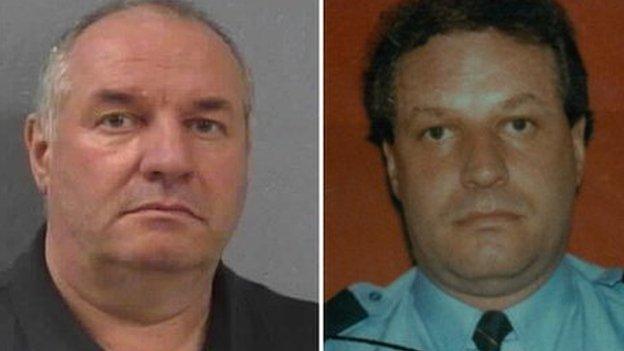

Five-year-old Thusha Kamaleswaran was left paralysed from the waist down after she was shot

"It would be very sad if a system were to evolve where people expected to be paid for providing evidence," he added.

However, often the prospect of a cash reward will still not be enough to persuade someone to come forward and, even if does, it can present problems if the case comes to court.

"What the police don't want to do is to contaminate evidence and the integrity of the investigation," Mr Howe said.

"If the person who is providing the information is actually a witness in the case, then the defence will, quite rightly, suggest and put in mitigation, that the evidence has been tainted by the inducement of payment. That is a major consideration for any senior investigating officer."

However, Mr Howe argued there was a case to be made for using cash rewards.

"If information can fast track inquiries - bearing in mind most major inquires/murder inquires are very expensive - there is an argument that... a short sharp injection of money can do that," he said. "I think you can argue it is good use of public money."

Crimestopper's operations performance manager Ian Froggett argued that rewards helped to keep crime lower by intimidating potential criminals.

As well as offering a standard reward of £1,000, the charity also offers "enhanced rewards" for particularly severe crimes.

It offered a £50,000 reward, along with the Association of Convenience Stores, for information after five-year-old Thusha Kamaleswaran was shot in south London.

It also offered £10,000 for information leading to the arrest and conviction of 25-year-old Joanna Yeates' killer Vincent Tabak and the same amount over the murder of Avtar Singh-Kolar, 62, and his wife, Carole, 58, who were killed in their Birmingham home.

During Britain's biggest cash robbery men loaded cash into a lorry in the loading bay of the depot

The money was largely raised initially by the charity's fundraisers but after high value robberies, the security industry often steps in to put up the cash.

For instance, after the largest cash robbery in British history - the £53m robbery at a Securitas depot in Tonbridge, Kent, in 2006 - the firm put up a reward of £2m for information, external.

Chief among their aims was to secure the return of the stolen cash and the convictions of those responsible for the robbery.

But it is still not clear how big a part cash rewards play in solving crimes. Crimestoppers says that "due to its anonymous nature" it is unable to say whether any particular crime has been solved with the help of rewards.

For Mr Howe, the fact we do not - and probably never will - know how often rewards are paid actually gives him "confidence in the system".

"It is a positive thing," he said. "I don't think we do know the answers, and it is to save the anonymity of the people involved that it is not disclosed."

- Published19 June 2014

- Published18 June 2014

- Published18 June 2014

- Published7 June 2014