Joseph Chamberlain: Man 'who made the political weather'

- Published

Joseph Chamberlain became mayor of Birmingham in 1873

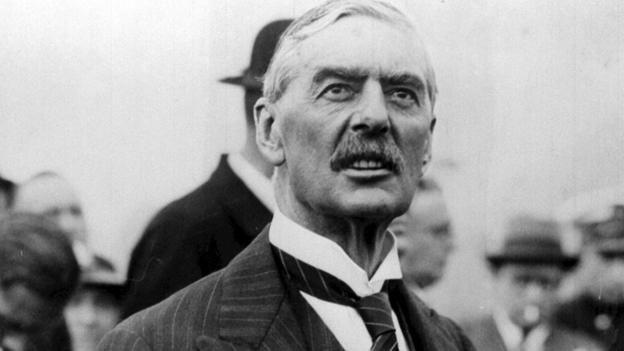

Winston Churchill once described Joseph Chamberlain as the man "who made the weather", the figure who shaped the political agenda when the British Empire stood at the height of its power.

He is also noted for the mark he left on Birmingham, including building schools, swimming pools and libraries.

He was the father of former Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain and Austen Chamberlain, who became chancellor of the exchequer.

Historians, government ministers and MPs are meeting in Birmingham to mark his achievements, 100 years since his death.

Joseph Chamberlain was born in Camberwell, London, on 8 July, 1836.

While attending University College School in London he also worked in his father's shoemaking business.

At the age of 18 he was sent to his uncle's screw-making business, Nettlefolds, in Birmingham, mainly to protect his father's £10,000 investment in the firm.

By his 30s he had made enough money to retire, but had garnered an appetite for local politics and in 1867 joined what was then Birmingham town council.

It was not granted city status until 1889.

"He was strongly influenced to get into politics by the Unitarian church who believed the only form of faith was what they called 'up and doing' - putting a civic gospel into practice," said Dr Ian Cawood, from Newman University in Birmingham.

"He was one of the more successful at doing this because he had great business sense and the money to support himself."

Chamberlain became mayor of Birmingham in 1873.

His first major decision was to buy both the Birmingham and Staffordshire gas companies and effect a hostile takeover of Birmingham Waterworks.

The following year he launched his £1.75m city improvement scheme, which used money from the gas industry and public funds to build libraries, schools and swimming pools.

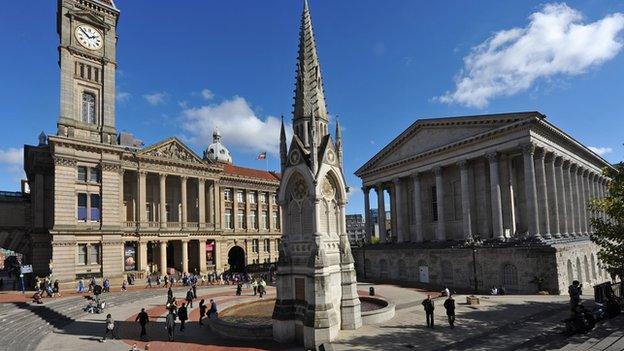

It also included clearing slum housing to build a "Parisian boulevard-style" road, Corporation Street.

Joseph Chamberlain's family home Highbury Hall in Birmingham is now used as a wedding venue

His legacy can still be seen across the city and includes the Victorian Law Courts on Corporation Street and his family home, Highbury Hall, built in 1880.

The estate, which includes Highbury Park, has been run by Birmingham City Council under the terms of a trust set up by the Chamberlain family in the 1930s. The hall is used as a wedding venue.

It was Chamberlain's achievements in Birmingham that catapulted him on to the national stage as Liberal MP for the then town in 1876 and President of the Board of Trade in William Gladstone's government in 1880.

Prof Peter Marsh, who wrote Chamberlain's biography in 1994, said: "Under his guidance Birmingham was known as the best-governed city in the industrial world.

"Although he had his critics, the thinking then was if you could carry Birmingham you could carry the country - it had huge national prominence."

The Victorian Law Courts opened on Corporation Street in 1891

The BBC's political editor for the Midlands, Patrick Burns, said: "His rise was fast - he was just over 40 when he became the first industrialist to hold a cabinet position.

"We have seen examples where people have been put forward after capitalising on local issues - David Blunkett was a big figure in Sheffield before he moved to government - but they tend to be the exception rather than the rule."

The Chamberlain memorial was erected in Chamberlain Square in Birmingham city centre in October 1880

Birmingham City Council leader Sir Albert Bore said he believed local authorities now yearned for a return to Chamberlain's values.

"He showed that a great city must not only have thriving businesses, but powerful civic institutions and governance that cares about health, housing and the education of its citizens," said the Labour politician.

"Today, we are far too reliant on central government for funding and hemmed in by regulations.

"I believe if we were given more freedom we could really drive economic growth and improve the lives of our citizens."

Dr Cawood said Chamberlain was seen as Britain's "first truly modern, professional politician".

He is credited as the first MP to print and hand out propaganda leaflets, much like today's election flyers, he said.

But while his public persona grew, his ambitions to land the job of prime minister all but ended in 1886, when he resigned from the government over William Gladstone's Irish Home Rule proposals.

"Chamberlain believed giving Ireland a separate parliament could lead to the eventual break-up of the British Empire," said Mr Cawood.

"It was a desperate mistake which left him on the wrong side of the government divide.

"He ended up having to become an ally of the Conservatives, but neither they nor the Liberals really wholly trusted him after that."

Following the setback Chamberlain became colonial secretary in Lord Salisbury's government in 1895.

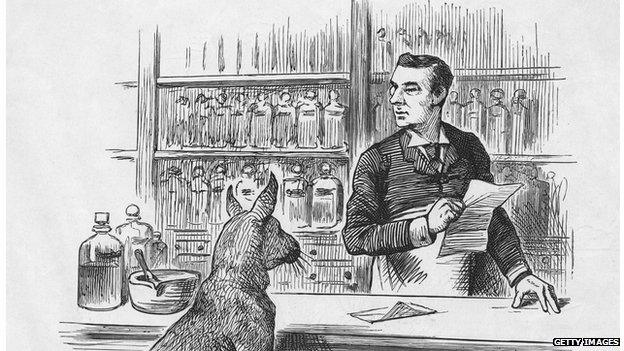

Joseph Chamberlain was drawn by cartoonists in publications such Punch

"His issue was empire building. He had worked to build up the screws business he had built up Birmingham and he used the same ethos for his work with the colonies," said Prof Marsh.

"He raised the Empire to the height of its power at the beginning of the 20th Century to see off the growing rivalry from France, Germany and the rising United States."

In September 1903, Joseph Chamberlain resigned from office so he could advocate a scheme abandoning free trade and imposing taxes on foreign imports.

The issue split the Conservative Party and resulted in a landslide victory for the Liberal Party in the 1906 general election.

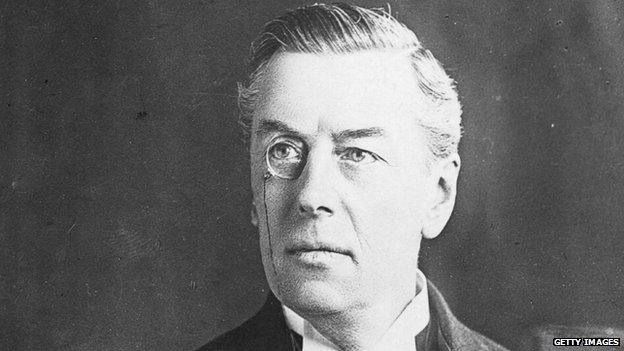

Joseph Chamberlain would always wear a monocle, and an orchid in his buttonhole

The following July, days after his 70th birthday, Chamberlain suffered a stroke that paralysed his right side and ended his political career.

He died in July 1914 and was buried in Keyhill Cemetery, Birmingham, after his family turned down the offer for him to be laid to rest in Westminster Abbey.

"In Birmingham there are tributes to him, but the name of Joseph Chamberlain is not as famous as you would expect based on the colossal influence he had in his day," said Patrick Burns.

"I think to some extent it's the passage of time; partly it is because he never became prime minister and when people hear the Chamberlain name they think of his son Neville who did get to number 10."

- Published30 September 2013